[ad_1]

In a video installation by James Joyce, a yellow circle rotates as two black ovals and a curved line tumble at the bottom, thwarted by gravity. Watching the video, Perseverance in the Face of Absurdity, which was projected at Banksy’s pop-up dystopian theme park, Dismaland in 2015, one can mentally reassemble the three shapes into their familiar formation: two eyes and a swooping smile.

It’s a testament to the symbol that it can be deconstructed to such a degree and yet still be immediately recognizable. There is no doubt that it’s a smiley face, though it looks anything but happy.

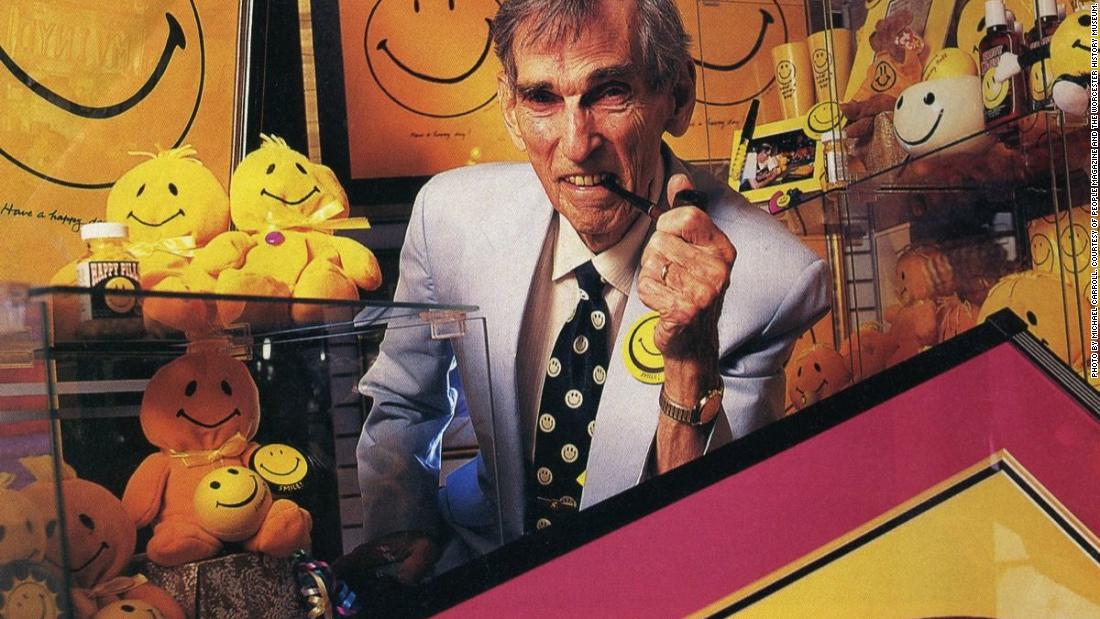

The yellow smiley icon was born in 1963 in Worcester, Massachusetts, when the graphic designer Harvey Ball was approached by State Mutual Life Assurance Company to create a morale booster for employees. As the story goes, it only took ten minutes for Ball to create an icon that would knit itself so firmly in the fabric of American culture that we’d be compelled to file lawsuits and contemplate it for decades to come. He was paid a whopping $45 for his work.

For such an enduring image, the logic behind it is almost laughably simple. Ball is often quoted as saying to the Associated Press, “I made a circle with a smile for a mouth on yellow paper, because it was sunshiny and bright.”

Photo of Harvey Ball from People Magazine, 1998. Credit: Photo by Michael Carroll. Courtesy of People Magazine and the Worcester History Museum.

The company produced thousands of buttons and signs, setting the stage for Hallmark reps Bernard and Murray Spain to swoop in in the early 1970s and copyright the design with the slogan “Have a Happy Day.” Just one year later, the French journalist Franklin Loufrani launched the Smiley Company, which grew into a global licensing giant.

At its core, the smiley is like any other symbol — a visual that has been assigned a specific meaning.

Why have these symbols at all? Marcel Danesi, an anthropology and semiotics professor at the University of Toronto, said that symbols are like “little capsules [that] tell us what things are about — in our own terms.” Not unlike language, they “form a kind of rhetorical system that undergirds a whole society. We live by symbols.”

The stability of this system is up for debate; symbols often exhibit the pliable quality of Play-Doh. On its face, the smiley is simple and feelgood, easy to learn and reproduce.

In the right context, it elicits that giddy childhood rush — the morale boost that inspired the image from the start. But stretched this way or that, the icon quickly becomes surreal. As Jon Savage penned for The Guardian in 2009, the smiley “presented such a fixed facade of childlike contentment that it was ripe for subversion.”

Over the years, the icon has been reimagined by bands like Nirvana and the Talking Heads, and it flourished in the rave culture of the ’80s and ’90s, imprinted on ecstasy pills and flyers for acid house DJs. Teen Vogue recently reported that “the playful symbol seems to be making a resurgence” in fashion, including on Marc Jacobs runways and in Justin Bieber’s line, Drew House.

The smiley has held a rare dual position as a countercultural icon and a paragon of American consumerism. The Smiley Company, which brought in $419.9 million in 2017, claims that the smiley is more than an icon, it’s “a spirit and a philosophy.” Though the company is global, this particular phrase strikes a very American chord. It presents an almost cult-like obsession with happiness — and what we can buy to achieve it.

When the icon appears in art, its meaning is often twisted or exaggerated. Nate Lowman has created childlike renderings of smileys, overlapped and colored outside the lines. Lowman, according to a 2012 New York Times profile by Jacob Bernstein, is “somewhat obsessed” with the face, “seeing in it a kind of collective mask — what he calls an ‘anxious hysteria to appear happy.'”

Paintings by artist Nate Lowman are pictured during the exhibition “Empire State. New York art now” in Rome on April 22, 2013. Credit: GABRIEL BOUYS/AFP/AFP/Getty Images

Various takes on the smiley have also appeared in Jacqueline Humphries’s emoticon-inspired pieces, including “:)

It’s hard to talk about the smiley face without broaching the subject of emojis, which we sprinkle into everything from Instagram posts to work emails. The smiley is no longer a standalone icon, but a single character in a visual online language.

Meet the inventor of the emoji

Though the invention of emoticons is commonly credited to Shigetaka Kurita of the Japanese telecom company NTT Docomo, the primary set of yellow smilies bear an undeniable relation to Ball’s original design. As more communication happens online, the smiley takes on a more nuanced range of emotions. It can be a stand-in for genuine happiness, or a balm for words that might otherwise sound harsh. The rise of emoticons has prompted a slew of studies and essays about the evolution of language online.

Given its uncurtailed proliferation, will the smiley ever lose its value as a signifier? If it can mean everything, then, surely, it will mean nothing. Danesi, however, seemed unconcerned by this existential threat to the happy symbol. The more meaning we apply to it, he suggested, the more staying power it will have — even if we don’t always know what to make of it. Or, even simpler: The smiley will persist because it’s cute.

Maybe, Danesi said with a laugh, he’ll go find a smiley t-shirt to wear himself, “so that I can bring sunshine into people’s lives.” Ironic or not, that may be reason enough to smile.

[ad_2]

Source link