[ad_1]

By Grace Aldridge Foster

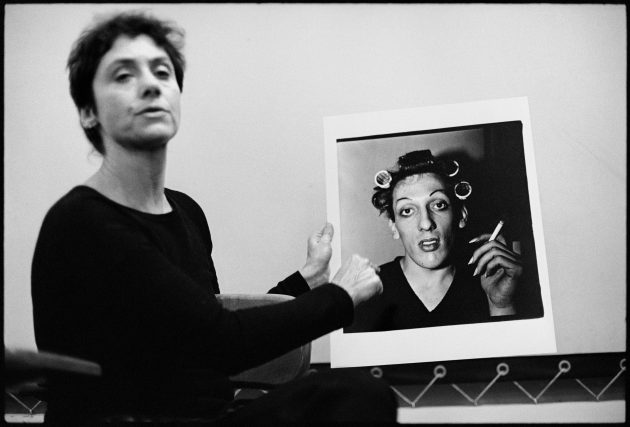

John Gossage, Diane Arbus in Washington Square Park, NYC, 1967, gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 in. Private Collection. (Photo copyright John Gossage)

Diane Arbus’ photographs are hard to forget. With her unusual subjects and a unique way of framing them with her camera, Arbus is considered one of the most important photographers of the 20th century.

Yet in spite of her elevated status in art history, Arbus’ most pivotal work has been largely overlooked until now.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s exhibition “Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs” sheds new light on the late stage of the artist’s career. The exhibition focuses on a set of 11 images that Arbus assembled in 1970 for Bea Feitler, her friend and former art director of Harper’s Bazaar.

Diane Arbus with her photograph “A young man in curlers at home on West 20th Street, N.Y.C. 1966,” during a lecture at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1970 (Copyright Stephen A. Frank)

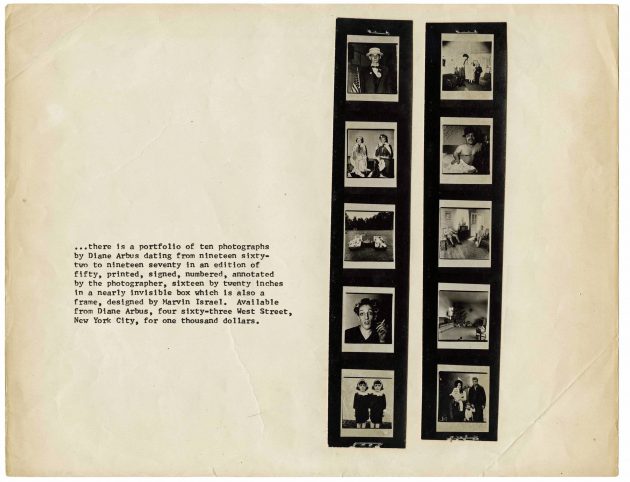

Arbus started eight sets of her “A box of ten photographs” portfolio before she died in 1971, but only four were completed. The box in the Smithsonian’s collection is the only one of the four that is publicly held.

The museum’s set is the beginning of an important story that hasn’t yet been properly told, says John Jacob, who curated the exhibition.

“The premise of this exhibition is that the box was the initial object in the trajectory that bridges her life and her much more famous posthumous work,” he says.

Despite its relative obscurity compared to some of her other work, this portfolio represented the turning point in the photographer’s career—and in the estimation of photography as art—and is the reason Arbus is known more widely today.

Diane Arbus with her photograph “Identical twins, Roselle, N.J. 1966,” during a lecture at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1970. (Coppyright Stephen A. Frank)

“It seems self-evident now that photography is art, but it wasn’t then,” Jacob says. “Somebody had to take that step, and it was with Arbus’ work that that happened.”

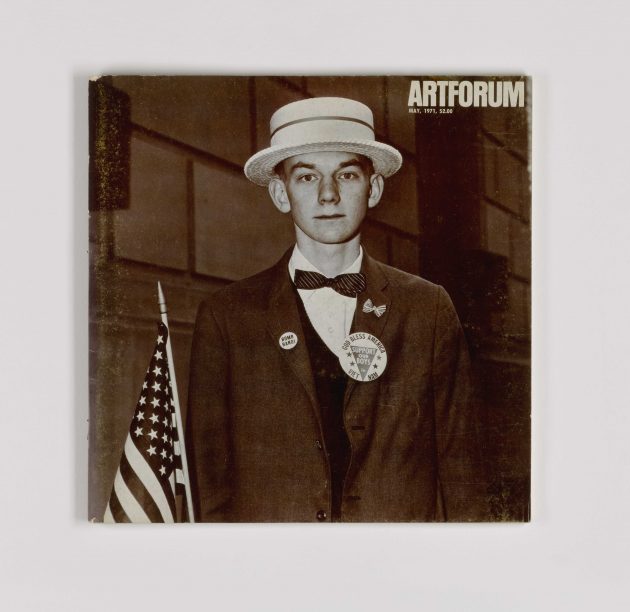

Shortly after completing a few of her boxes, Arbus was chosen as the first photographer ever to be highlighted in Artforum magazine. Her photograph of a “patriotic boy with straw hat, buttons and flags waiting to march in a pro-war parade in N.Y.C” (1967)—one of the 10 photographs from her box—graced the cover of the May 1971 issue.

This was a coup for Arbus and for photography itself, but she died a few months after the Artforum feature. The next year, her work was chosen to represent the U.S. at the Venice Biennale, the premier international art festival. No photographer had been included in the Biennale until Arbus.

Before Arbus broke onto the art scene, photography had mostly reached the public through magazines, which is how Arbus made a living.

Diane Arbus, “Boy with a straw hat waiting to march in a pro-war parade,” cover of Artforum, May 1971 (Copyright The Estate of Diane Arbus/Copyright Artforum, May 1971, “Five Photographs,” by Diane Arbus. Photo by Mindy Barrett)

“She was a magazine photographer with a vision that was larger than what the magazines could contain,” Jacob says.

Arbus was also a writer, which informed the way she assembled her boxes. She included a sheet of translucent vellum between the photographs in the box, and she wrote an inscription at the bottom of each sheet describing the photograph that was vaguely visible underneath. She wrote pieces to accompany her magazine photographs as well.

“It’s what I’ve never seen before that I recognize,” she wrote in the essay that accompanied her 1971 feature in Artforum.

Diane Arbus, Promotional flyer for “A box of ten photographs, 1970-1971,” two gelatin silver contact sheet strips affixed to paper support, with Arbus’s typed offering information, unframed. (Copright The Estate of Diane Arbus, photographs courtesy Torin Stephens, Fraenkel Gallery)

Arbus often photographed people whose professional, personal or physical attributes deviated from what was considered normal or acceptable in her time, like carnival performers on Coney Island or nudists. She wasn’t alone in choosing that subject matter, but what made her work so different, Jacob explains, is the way she approached her subjects.

“She’s physically closer to them, she’s intimate, and the way she photographs them, we share the space between the photographer and the subject,” Jacob says. “I think she was very special in breaking that wall of objectivity and making us feel like we share the space with her.”

For example, in one of the photographs, “A Jewish giant at home with his parents in the Bronx, N.Y.” (1970), she includes the arms of a chair in the lower frame, so it’s as though she—and we—are sitting there, watching Eddie the giant interact with his parents in their living room.

Stephen Frank, Diane Arbus with her photograph “A family on their lawn one Sunday in Westchester, N.Y. 1968,” during a lecture at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1970. (Copyright Stephen A. Frank)

Arbus pioneered a new printing technique with the photographs in the boxes that contribute to a sense of physical presence and intimacy. Instead of printing them with a black border, as she had often done, she reversed her technique to produce a soft, slightly irregular edge to her photographs. The effect limits the separation between the photograph and the viewer.

One of the photographs that best exemplifies the emotionally complexity of Arbus’ work isn’t even officially part of the “box of ten photographs”; it is number 11.

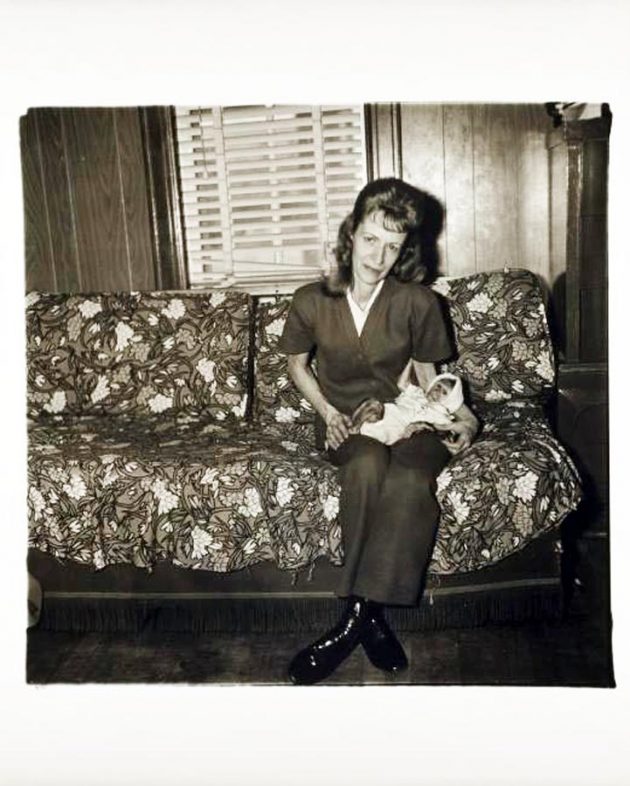

In two of the four box sets Arbus sold, she chose an 11th photograph just for the buyer. The one she gifted to Bea Feitler depicts a woman sitting on a couch in a wood-paneled room, holding a baby monkey dressed in a bonnet and clothes on her lap. The woman looks for all the world like a proud mother.

“A woman with her baby monkey, N.J. 1971.” (Smithsonian American Art Museum; museum purchase. Copyright The Estate of Diane Arbus)

Jacob can’t choose a favorite, but he does love this photograph “because it’s so peculiar.” It was made on assignment for the Life Library of Photography: The Art of Photograph (New York: Time, Inc., 1971), under “Responding to the Subject: Assignment: Love.” Jacob adds, “It’s a mysterious photograph. It’s awkward, and interesting to look at.”

Arbus didn’t intend for her “box of ten photographs” to be a quintessential set. As many of the notes and letters in the exhibition reveal, her key motivations were income and to establish a stable stylistic identity. Because she died while making the boxes, Jacob says, the images it contained are among her most iconic. “It’s the way the world got to know her first,” Jacob says.

“Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs” is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through Jan. 27, 2019. The exhibition is accompanied by a special catalog that traces the history of “A box of ten photographs.”

[ad_2]

Source link