[ad_1]

Growing up I heard many stories about my parents’ involvement in the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, a collective dedicated to eliminating racial discrimination. What started as a protest of racist practices in one automotive factory quickly moved beyond the plant to include “neighborhoods, schools, and places of recreation” throughout southeastern Michigan.

As someone who now studies organizations, when I think about the League I am struck by how fortunate it is to have a record of its activities. Most organizations, especially those started by Black people, are not so lucky. The paltry historical record means that we have a limited ability to appreciate the range of organizations started, transformed, and operated by Black people. My concern extends beyond organizations connected to freedom struggles like the League to all organizations that sustain Black life and community.

The historical record is incomplete for many organizations. This presents a series of challenges for scholars. Finding relevant data being chief among them. Say, for instance, that a researcher wants to study how the average number of teachers per school within Massachusetts varied across the twentieth century. It’s only recently that federal and state governments began amassing consistent data about schools and teachers. This researcher would likely have to search through local and county records that vary in quality of documented information about schools and teachers in the twentieth century, if they documented such facts at all.

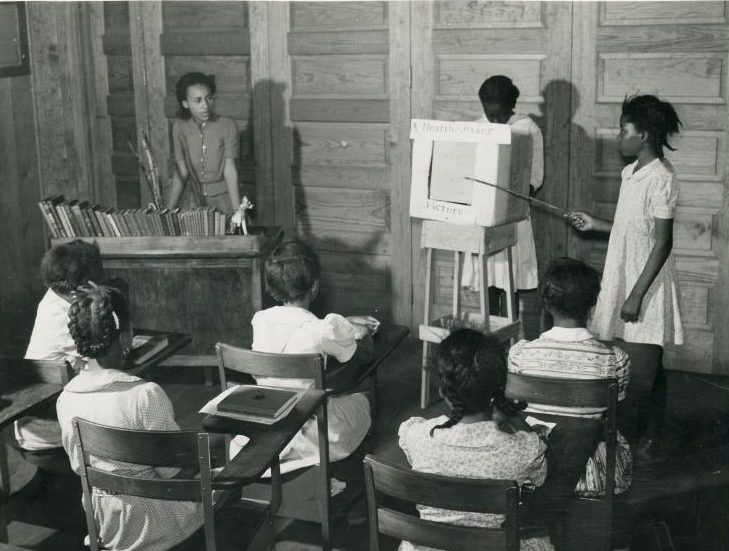

When the interest is in organizations related to Black life, the challenge of finding information is magnified because it was quite common for those in charge of collecting data to skip over Black organizations altogether. For instance, the federal government did not always gather data on Black schools outside of seminal studies produced decades apart. This lack of data has complicated my own quest to understand how schools support Black life and community.

Tracking down information on Black schools has taken me to archives, historical societies, and libraries across the United States. Typically, someone thought to preserve the materials in these places not because of what the records would tell us about the Black organizational past, but because this history was tied to powerful white people like John D. Rockefeller or Julius Rosenwald who at times provided money for the schools I’ve studied.

Finding information about Black organizations lacking ties to such influential white people is challenging. But as the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture collection illustrates, doing so is not impossible. Many artifacts now on display were preserved as family keepsakes passed along from one generation to the next. Capturing the full extent of the Black organizational past will require many similar acts of recovery.

The renewed interest in the Negro Motorist Green-Book illustrates how much we can gain from unearthing the history of Black organizations. Interstate travel for Black Americans during Jim Crow posed serious risks of harm or death. Knowing where to go was key to staying safe. The Green-Book listed business establishments, particularly hotels and tourist homes, that welcomed Black travelers.

Thanks to the Green-Book we can estimate how many businesses welcomed Black guests in cities across America at the height of Jim Crow. Yet the Green-Book raises more intriguing research questions. How did these businesses, many of them Black owned, get the resources they needed to survive? Did the businesses in the Green-Book have access to credit? If so, who were the lenders? How many beds did the average hotel have? How much revenue did the average restaurant make per quarter? How big was the average establishment in the Green-Book? Did the businesses develop any relationships with one another as a result of inclusion in the Green-Book?

The Green-Book was the Airbnb of its day for Black travelers. The listed properties comprised a sharing economy long before we had a label for this type of business activity. But we do not know the scale and scope of this economy because, like so many facets of Black history, this one went largely undocumented. We also do not fully appreciate the skill involved in creating such economies. Victor H. Green solicited recommendations from his fellow Black postal carriers to identify listings for the Green-Book. He leveraged an existing organization, the postal service, to build a new one.

We will have to look through attics, interview descendants, and turn to unexpected places to find further tales of Black organizations. The search will be long, hard, and winding but ultimately essential if we hope to understand how organizations nurture progress within the Black community. As the Green-Book illustrates, digging into the organizational past provides insight into the relationship between enterprise, oppression, and survival endemic to Black American life. Centering the creativity and innovation that it takes to form organizations that move communities closer to equality will enhance the study of Black social and cultural history.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

[ad_2]

Source link