In the article below New Jersey historian Dr. Joseph A. LaRosa allows us a glimpse into the rarely discussed last two national conventions of the Niagara Movement that took place in 1909 and 1910, in Sea Isle City, a small oceanside community in Cape May County, near the southern tip of the Jersey shore. Dr. La Rosa describes the important role of these meetings as the prelude to the incorporation of the Niagara Movement into the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In 1909 and 1910, Dr. W.E.B. DuBois and other Black leaders converged on the small southern New Jersey coastal community of Sea Isle City to carry on the work they had begun in Niagara, Ontario, Canada in 1905 to combat both ongoing racial discrimination in the United States and equally important, what they felt were pernicious effects of Booker T. Washington and his supporters who seemed intent on suffocating a robust challenge to that discrimination.

The Niagara Movement was launched in the summer of 1905 at Fort Erie, Ontaria, Canada and took its name from nearby Niagara Falls. There 29 men met to plan strategies to combat the two greatest challenges facing Black Americans at the time, racial segregation and disenfranchisement both of which had grown from the end of Reconstruction from issues initially affecting the ex-Confederate states, to national racial policies as reflected in the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court Decision in Plessy v. Ferguson that allowed “separate but equal” to be the law for the entire country. In reality, however, as many across the country knew and certainly as all the Niagara Movement members knew, accommodations throughout the United States were nowhere near “equal” between the races.

W.E.B. DuBois was the leader of this fledgling movement. The first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1895, by 1903 his book, The Souls of Black Folk, was the first major challenge of Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist policies toward racial injustice. By 1905 a handful of other intellectuals and “race leaders” dared to challenge Washington not simply in words but through an organizational response to both accommodation and nearly universal racial discrimination. Niagara, however was more than just opposition to disproportionate control the Principal of Tuskegee Institute had on national Black politics, it was viewed by its supporters as the best vehicle to attain full rights for Black Americans.

As the group grew, subsequent meetings were held at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia in 1906, Boston, Massachusetts in 1907, and Oberlin, Ohio in 1908. Each site had symbolic importance in the struggle for racial justice. Harper’s Ferry was the setting for John Brown’s doomed attempt to promote a mass servile uprising in 1859. That three-day Meeting in West Virginia between August 15 and August 18, was held on the campus of Storer College, a small HBCU, and drew an estimated 50 attendees including for the first time, seven Black women. Boston, Massachusetts was arguably the American city which produced Black and white leaders most sympathetic to the abolitionist movement before the Civil War and most opposed to segregation and discrimination in the post-Civil War period. That meeting at Faneuil Hall attracted 100 attendees. Oberlin was a center of abolitionist sentiment in the Midwest before the Civil War and home to the midwestern college that was the first in the nation to promote both racial and gender equality through its diverse student body. We don’t know how many people attended the Oberlin meeting because by that point the Booker T. Washington-controlled Black press gave little attention to the gathering.

By that point, however, internal divisions and attacks from Booker T. Washington and his powerful allies and supporters were already beginning to undermine the Niagara Movement. There was also trouble within the Movement. Divisions between William Monroe Trotter and DuBois first surfaced in 1906 over whether women should participate in the Movement. Trotter eventually dropped his opposition, and seven women attended. Soon after the Boston Meeting in 1907 in Trotter’s hometown, he and many of his followers abandoned the organization. So few Movement members attended the 1908 meeting at Oberlin which ran from August 31 to September 2, that Washington’s supporters prematurely announced the end of the Movement.

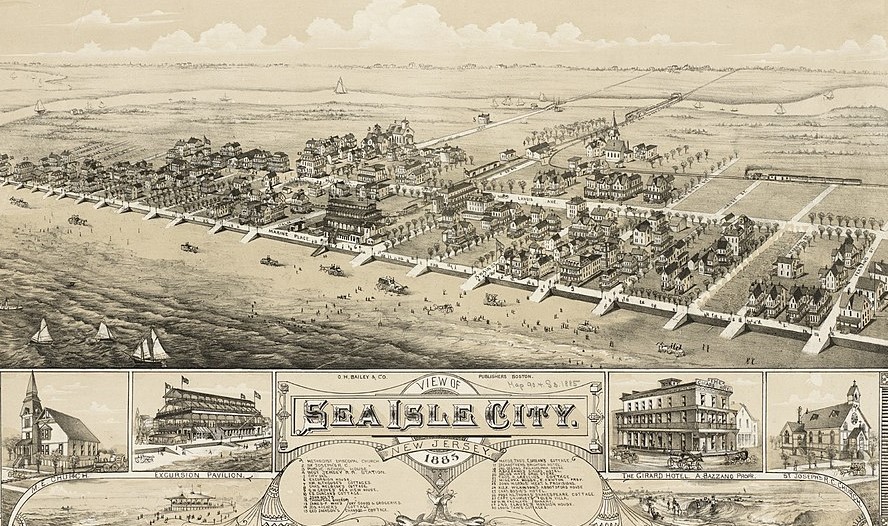

Sea Isle City, New Jersey, the site of the final Niagara meetings in 1909 and 1910, shared none of the history and symbolism of Harper’s Ferry, Boston, or Oberlin so its selection twice needs some explanation. While we will never know completely why this small community of 551 people (1910 census) near the southern tip of the Jersey shore was chosen, there are a few crucial factors. The delegates stayed at the Gordon Sea View Hotel, a rare Black-owned beachfront property situated between Hartson Avenue and the Atlantic Ocean, on what is now 37th Street. This is the current site of the Spinnaker Condominiums. Although advanced reservations for Meeting were directed to J. H. Gordon in Brooklyn, New York, the proprietor of the Gordon Sea View Hotel was Jasper L. Evans, a Black entrepreneur. Evans owned other hotels and businesses throughout the area and was a Director of The Peoples Savings Bank which was described in the New York Evening Press on August 6, 1909, as the first Afro-American bank in North Philadelphia. At the time there were fewer than a dozen Black-owned banks in the United States which made Evans one of the nation’s most prominent Black businessmen. The president of the bank was George Henry White, who was also the founder of the community of Whitesboro in nearby Middle Township, New Jersey, only 16 miles south of Sea Isle City.

Before moving to New Jersey, George Henry White represented North Carolina’s 2nd District in the U.S. Congress between 1897 and 1901. White was the last of a series of Southern African American Representatives elected to Congress during and after Reconstruction. Although his Congressional term expired in 1901, he remained one of the most recognized figures in the national African American community. Niagara Movement members may have thought by choosing a Black-owned hotel on the Jersey shore near an all-Black community founded by the last sitting African American Congressman of the era, they were making a bold endorsement of the potential for Black economic success. DuBois knew Gordon because of their correspondence, and he certainly knew of former Congressman George Henry White.

The Niagara Meeting ran in Sea Isle City between August 15th and 18th 1909. Advertisements in some Black newspapers at the time indicated that the railroads granted reduced round trip tickets to New Jersey Seaside resorts during August and called on would-be participants to check with their local ticket agents to determine the fare to Sea Isle City. One ad that appeared in the Indianapolis Freeman on August 7, 1909, described the rates at the Gordon Sea View Hotel as between $1.50 per day or $10.00 per week for longer stays. Included in the $1.50 daily rate were “Board, furnished room, and electric lights.” The hotel was listed as being on the Boardwalk. Also, Sea Isle City was noted as having all the usual amusements and attractions of New Jersey seaside resorts including fishing, boating, sea bathing, and an amusement pier. The Indianapolis Freeman ad made it a point to note that women and children were welcome at the hotel.

The Conference opened on Sunday, August 15, 1909, and ended on Wednesday, August 18, 1909. According to a September 4 description in the Savannah Tribune, much of the annual meeting was held at the Methodist Episcopal Church (white) which was located on the southeast corner of Landis Avenue, and what is now 45th Street. On August 15, according to the Tribune, W.E.B. DuBois gave an address at the Sunday morning service to conference attendees and local residents and explained the purposes and aims of the Niagara Movement which he said “showed that the cause of all submerged classes and peoples is practically the same.”

An August 23, 1909, account in New York Evening Post, a rare white newspaper that covered the meeting, listed the topics discussed which included “Methods of Emancipating Submerged Peoples, The Methods of Socialism, Methods of the Russian Revolution, Methods of the Mexican Liberals, Methods of Modern India, Methods of Organized Labor,” and “The Lesson of these Methods for Negro Americans.” The Meeting also addressed the ability of African Americans to freely travel and condemned mob rule and lynching. Despite its dwindling national support, the Meeting still called for the founding of a monthly publication and the purchase of a permanent meeting place. At the Meeting’s conclusion and following the pattern of all previous national gatherings, a statement was drafted, and a plan was proposed for future action.

Not surprisingly major newspapers continued to ignore Niagara Movement meetings and most of the Black press under the control of Booker T. Washington disparaged Sea Isle City gathering. On anti-Niagara newspaper, the Indianapolis Freeman, wrote derisively on October 9 that DuBois’s “Statement to the Nation at the Conference conclusion could have been done at the secretary’s desk at home…and saved a few persons several dollars in train fare.”

By the time of the 1910 meeting there were far fewer people following the Niagara Movement nationally and subsequently fewer attendees at the annual meeting. Once again, the Gordon Sea View Hotel served as the meeting’s headquarters. The Conference met in Sea Isle City from August 27 through August 30, 1910, in what would be the last gathering of participants in the Niagara Movement. Sensing that the organization was in rapid decline, the theme at this meeting was “Concentration of Effort Through Race Organizations.” At the end of the meeting DuBois gave his annual address to the country. The address noted five areas of focus, all of which were thinly veiled attacks against Booker T. Washinton and his accommodationist strategy. What proved, however, to be the most important part of the address was articulated at its conclusion. As recalled by an article in the Washington Bee, ironically a leading anti-Niagara paper on September 3, 1910, DuBois’ report to the nation stated:

“Finally, we recognize as the greatest accomplishment of the year, the organization of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in New York City. We urge our members to join and co-operate with it, and we willingly entrust to this organization the carrying out of the great objectives of political enfranchisement, universal education, legal protection, and social justice.”

Essentially the Niagara Movement publicly acknowledged that the interracial National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded a year before in 1909, was now the most effective organization to assist African Americans in their struggle for racial justice in the United States. This groundbreaking statement was written at the Gordon Sea View Hotel in Sea Isle City, New Jersey.

The role of Sea Isle City in helping to merge the Niagara Movement with the newly created NAACP went unnoticed and forgotten in the official accounts of both organizations and in the collective memory of Sea Isle City residents for many years. In the spring of 2024, however, that role came to the attention of Mary Ellen Balady, a retired municipal employee from Mercer County, New Jersey. Ms. Balady was researching other Black History issues in the area when she came across the reference to Sea Isle City in the last years of the Niagara Movement. Ms. Balady contacted the Sea Isle City Historical Museum, and they agreed to have the last two Meetings of the Movement memorialized by markers and included on the New Jersey Black Heritage Trail created in 2022 by then Governor Philip D. Murphy. Meanwhile Sea Isle Museum personnel continue to research Sea Isle City’s role in the Niagara Movement and its relationship to the emerging NAACP. This remarkable story is not over.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Accounts of the Niagara Movement Meetings can be found in various newspapers including the New York Age, the Indianapolis Freeman, the Savannah Tribune, the Cleveland Gazette and the New York City Evening Post. For additional background see “The Niagara Movement Digital Archive,” W.E.B. DuBois Library, University of Massachusetts, Amherst; Angela Jones, African American Civil Rights: Early Activism and the Niagara Movement (New York: Praeger, 2011); Thomas Aiello, The Battle for the Souls of Black Folk: W.E.B. DuBois, Booker T. Washington, and the Debate the Shaped the Course of Civil Rights (New York: ABC-CLIO, 2016); and Kerri K. Greenidge, Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter (New York: Liveright Publishing, 1919).