[ad_1]

Keith Sonnier, who starting in the 1960s expanded notions of sculpture with materials including fabric, foam, and incandescent light, died on Saturday at the age of 78. He passed away from causes related to a long-time illness at Southampton Hospital near his home in Bridgehampton, New York, his studio confirmed.

Sonnier came up as part of a cadre of artists remaking and rethinking modes of sculpture and other kinds of art in downtown New York City, where disciplines collided and collaboration (however directly or indirectly) was key. His best-known works made use of neon light, which for him became a medium for electrified drawing that could look loose and ephemeral, as if sketched with a sense of freedom and ease at odds with the realities of planning and fabrication. Light in his hands could squiggle and twitch; it could feel alive.

“The viewer is inside the light,” he once told ARTnews about his early “Ba-O-Ba” series, inspired by a story he had heard about fishing under the moon. “You are in the moonlight so to speak, bathed in light … very biblical.”

As a sculptor Sonnier started working with found objects and stray materials outside the conventions of fine art that had been handed down from the past. Instead he opted for a disparate array of materials that ranged from satin, rubber, and felt to radios, police scanners, and antennae. An installation titled Dis-Play II—dating back to 1970 and re-created for the Dia Art Foundation’s Dan Flavin Institute in Bridgehampton, New York, in 2018—enlists otherworldly washes of light along with foam rubber, fluorescent powder, and projected films.

“Our type of work was somehow counterculture,” he told Interview magazine. “We chose materials that were not ‘high art’; we weren’t working in bronze, or paint, even. We were using materials that weren’t previously considered art materials. They were deliberately chosen to psychologically evoke certain kinds of feelings. I use psychologically loaded materials.”

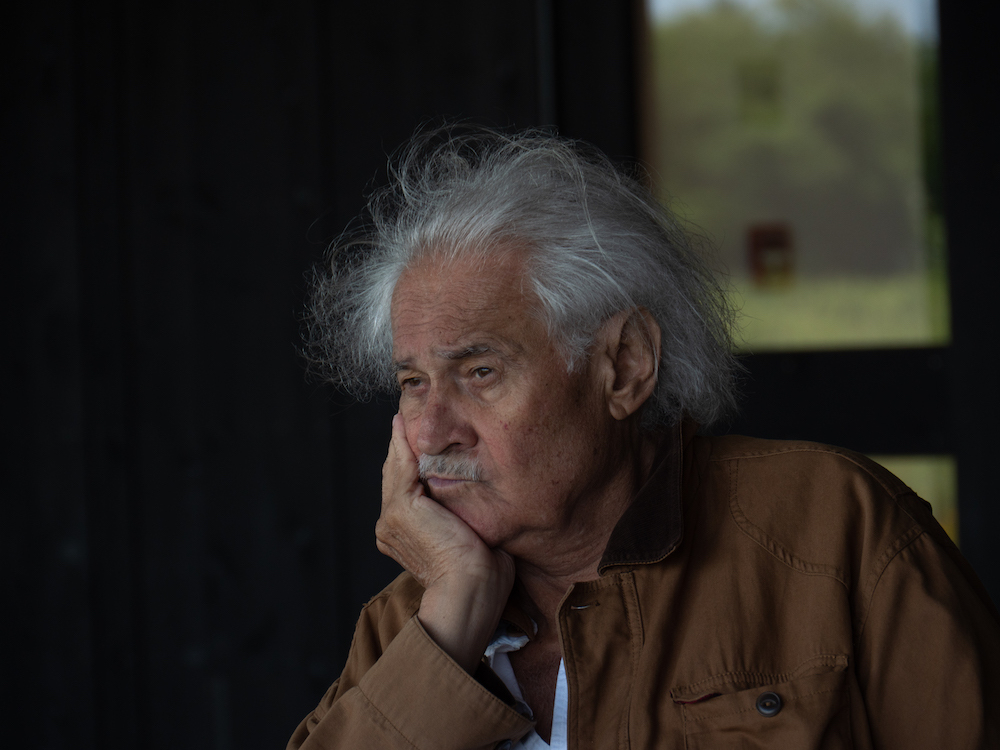

Courtesy Keith Sonnier Studio

Keith Sonnier was born in 1941 and grew up in a Cajun family in rural Louisiana, home to other Bayou State natives in his later downtown New York milieu including Lynda Benglis, Richard “Dickie” Landry, and Tina Girouard. He studied art as a graduate student with Robert Morris at Rutgers University in New Jersey and found a sympathetic home in a burgeoning SoHo scene charged by exploratory work by Gordon Matta-Clark, Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Barry Le Va, and many others.

Sonnier was not alone in his use of neon in the late ’60s. “But while figures like Joseph Kosuth and Bruce Nauman used the medium around the same time to wryly challenge the conventions and limitations of language, Sonnier embraced neon as a means to stretch the definition of drawing,” Charlie Tatum wrote in an Art in America review of a 2018 survey exhibition organized by the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York. “Early examples like Neon Wrapping Incandescent II (1968) use neon tubing as a way to sketch in three dimensions. This work’s interlocking loops of red and blue and its draped black cords are like luminous doodles.”

Courtest Keith Sonnier Studio

Sonnier spoke of his light works as passionate renderings. “A lot of the impulses came from an erotic, sensual—they were more understood if they were felt,” he said of his earliest neon creations in Bomb magazine in 1982. And the feelings they evoke can work in different ways at different scales, from smaller wall works to monumental ones like Lichtweg, an installation along a 1,000-meter corridor at the Munich International Airport that took form in 1992 and remains today to be experienced.

“Becoming engaged with neon was magical to me,” Sonnier told the Brooklyn Rail in 2018, reminiscing around the time of his Parrish Art Museum survey. “I think in art making there is always a magical element. I think it’s innate in art making and in art perception and viewing. And that’s why I like to get people to go and see art.”

[ad_2]

Source link