[ad_1]

Sara Cwynar, Tracy (Gold Circle), 2017, dye sublimation print on aluminum.

COURTESY THE ARTIST; COOPER COLE, TORONTO; AND FOXY PRODUCTION, NEW YORK

Earlier this month, when asked what’s been on her mind recently, the artist Sara Cwynar rattled off a long list—the colors of the newest iPhone model, Lauren Berlant’s theories about desire and capitalism, plastic surgery in China, and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s writings about color. Cwynar, 33, was sitting in her studio—a third-floor walk-up in Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighborhood that looks out over an auto repair shop—on a sweltering day this past September, and was explaining that Wittgenstein theorized that two people might perceive hues in two different ways. In the 20th-century German philosopher’s view, those differences can’t be discussed, however, because it’s so hard to communicate the way we see color.

“If we don’t know we’re seeing the same colors,” Cwynar said, “how do we know anything is true at all? Why do we care about what someone is telling us about how we should be described by a whole history of photography or capitalism or advertising?” She paused for a few seconds, laughed, and added, “But that sounds really stoner-y.”

Cwynar’s photographs and films regularly tread this line between high-theoretical thinking and jokey self-criticism. Over the past few years, she has addressed the overabundance of advertisements today, investigating how such pervasive marketing defines notions of beauty and stokes consumerism. Though her concerns are reminiscent of some 1980s Pictures Generation artists, her art is attuned to the rush of advertising and persuasion that now flows through screens and feeds, and it has quickly earned her a following.

Having appeared in the 2015 edition of the Greater New York quinquennial at MoMA PS1 in New York, Cwynar is now showing her densely collaged work at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, in her first-ever museum show, and in a section of the 2018 Bienal de São Paulo curated by artist Alejandro Cesarco, where she debuted Red Film, the final work in a trilogy of films she’s made about color and desire.

Installation view of Sara Cwynar’s Red Film (2018) at the Bienal de São Paulo.

©LEO ELOY/ESTÚDIO GARAGEM/FUNDAÇÃO BIENAL DE SÃO PAULO

Red Film loosely focuses on the Japanese makeup line Cezanne, using its powders, lipsticks, and eyeliners as an entry point for an inquiry into how ideas are produced and disseminated. Shots of these makeup products being applied by pairs of hands (the “hands of advertising,” as Cwynar called them) are intercut with images of paintings being readied for storage and the artist herself hanging upside down against hotly colored backdrops. Two narrators—an unidentified male and Cwynar—read cooly from what sounds like a theoretical manifesto; their words accompany a rhythmic montage of dancers twirling, liquid makeup dripping, and reproductions of ancient artworks being printed. (Their dialogue is a bricolage of phrases and sentences from diverse sources, ranging from Roland Barthes in the 20th century to a speech by Queen Elizabeth I in the 1500s. It’s not until the film’s closing credits that viewers learn this.)

The film, Cwynar said, speaking with her usual exuberance, is about “the pressure to buy things and to look a certain way, which are very connected for women and are very limiting, since they’re sold to you as a freedom or a power, a way of having agency in the world.”

True to its title, the film is punctuated by shots featuring fiery scarlet lipsticks and smoldering crimson fabrics. But red only became key for the film after it was done, Cwynar said. As she was creating the work, she thought of how cameras can’t register reds as they appear in real life—a picture of a ruby-colored shirt may appear closer to wine-red on film or in a photograph, for example. She allowed this slippage to become part of the film’s framework. “I wanted to bring to the forefront the ways that intangible things get standardized,” she told me, “that notions of truth . . . are actually decided by someone and handed down.”

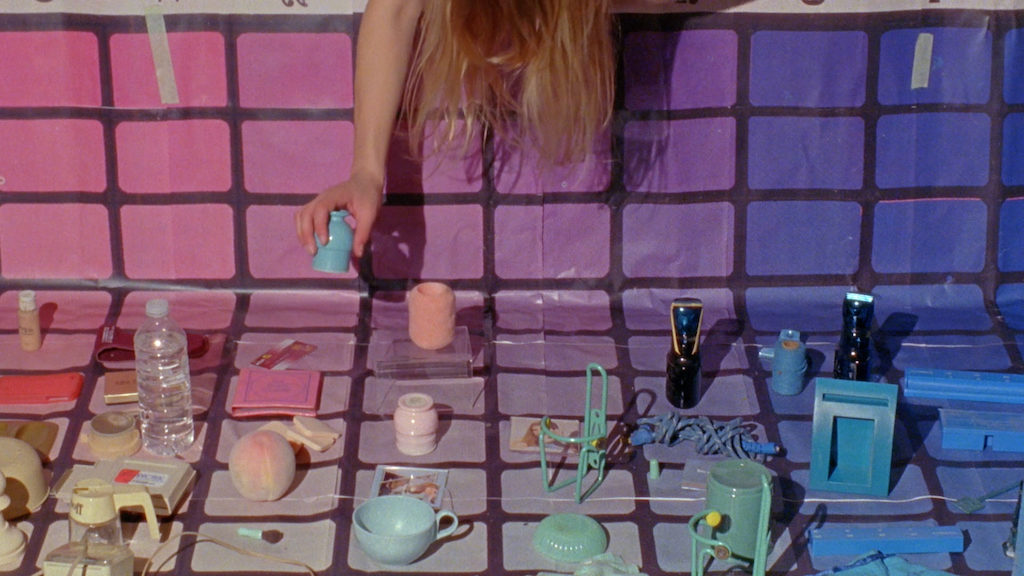

The day I visited her studio, Cwynar had one of her collaged-looking photographs on hand—a still life featuring a picture of her friend Tracy as its base, with all kinds of trinkets piled up on top of it. (The work would soon be shipped to Frieze London in October, where Toronto’s Cooper Cole gallery showed it.) Nearby, she was at work on another. An old-timey camera was suspended above perfume bottles, found pictures of women wrestlers, and makeup cases, some of which were placed between sheets of glass; when photographed, these objects would appear flattened like pressed flowers, or cut-and-pasted as though edited in Photoshop. The assortment of objects was drawn from Cwynar’s holdings, which sprawl across her studio and her apartment.

Sara Cwynar, Rose Gold (still), 2017, 16mm film on video, 8 minutes.

COURTESY THE ARTIST; COOPER COLE, TORONTO; AND FOXY PRODUCTION, NEW YORK

Though her works often survey their source material with a cold gaze, Cwynar has a sincere attachment to many of the objects that pass before her cameras, and she collects them avidly. To find objects for her films, she sometimes picks through boxes of refuse on the street, though most of her searching is done online, on sites such as eBay, where she will “tap out the whole market” for a certain object. “I think I own every gold presidential Avon cologne bottle that was on eBay,” she said, before admitting with a twinge of regret that “maybe there are some new ones now.” Melamine plastic cups were another obsession.

Most of Cwynar’s subjects evoke a certain fondness for the days of yore—and it’s no wonder their former owners no longer want them. She told me that her interest in nostalgia stems from her time at the New York Times’s graphic design department. Times editors would send the department profiles and trend pieces, and the designers would be charged with determining how best to visually communicate them. “We’d have these meetings about how an audience of millions of people was going to understand an image or design,” she said. “That’s something I still think about so much—how you can try to control things, but once you put it out into the world, it takes on a life of its own so quickly.”

Advertisers are engaged in a similar process, of course, passing along various biases and assumptions as they try to peddle things—Cezanne, for instance, borrows the name of a French Impressionist to sell whiteness to their consumers, many of whom are not white. It all makes one wonder who is ultimately in charge of shaping and transmitting such artificial ideals. “This is one of the reasons I make art,” Cwynar said. “It’s a way of controlling the world.”

[ad_2]

Source link