[ad_1]

Installation of “Contemporary Muslim Fashions” at the de Young. Ensembles by Peter Pilotto, and Mary Katrantzou, Yves Saint Laurent and Rebecca Kellett.

COURTESY OF THE FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO/JOANNA GARCIA CHERAN

Thanks to the success of retrospectives devoted to designers like Alexander McQueen, Yves Saint Laurent, and Jean Paul Gaultier, fashion exhibitions have become staples at many major museums. But “Contemporary Muslim Fashions,” at the de Young Museum in San Francisco is a game changer. It has no big name, and it’s about a demographic that, in the West, is generally not associated with cutting-edge fashion, emphasizing modesty over sexuality. For many Westerners, the very idea of Muslim fashion may be an oxymoron.

And yet, this overdue exploration of the complex, multifaceted world of Muslim fashion has been largely well received, perhaps signifying a turning point in mainstream America’s appreciation of the interplay between faith, feminism, and identity.

The de Young is the first major museum to host an exhibition on the topic of this scale. Max Hollein, the former de Young head who is now the director at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, said he became intrigued with Islamic fashion while serving on the board of the Istanbul Modern museum. Through his travels to Istanbul and Tehran, he began to view fashion as a means of communication, one that could build bridges.

Naima Muhammad for House of Coqueta (est. United States, 2010), Ensemble: Asymmetric tunic, gathered ankle.

COURTESY THE ARTIST/IMAGE COURTESY THE FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO

“It can be about art, design, and everything else,” Hollein said in interview in San Francisco last year, before leaving for the Met. “It’s a coded language with multiple access points. To a certain extent, fashion sometimes can be a more complex, apt communicator than even a painting.” Though Hollein did not curate the exhibition, he was involved in developing the overall concept, forming an international advisory committee that included journalists, academics, and curators, and introducing its organizers to Sheikha Moza of Qatar, who lent couture pieces from her collection.

Not surprisingly, before the show even opened, some in the blogosphere questioned why a major museum would promote Islam while others accused the de Young of celebrating the oppression of women. “We certainly did not want to provoke,” Hollein said. “But one quarter of the world’s population is Muslim. So the idea that we shouldn’t be exhibiting Muslim fashion is completely bizarre.”

Women were the driving force behind the exhibition. The majority of the designers and artists featured are female, the stunning galleries were designed by Iranian-born sisters Gisue Hariri and Mojgan Hariri of the celebrated firm Hariri & Hariri Architecture in New York, and the show’s curators, Jill D’Alessandro and Laura L. Camerlengo, who are both curators at the Fine Arts Museums (which includes the de Young), are both women.

The 80 ensembles on display in the exhibition, which is on view through January 6, before traveling to the Museum Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt, Germany, come from across the Middle East, Indonesia, Europe, the U.K., and U.S. Among the highlights are London designer Sarah Elenany’s hip-hop influenced street styles, sumptuous batik ensembles by Indonesian designer Dian Pelangi, and couture gowns from Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, and Karl Lagerfeld.

The show comes at a time when an American president routinely makes Islamophobic comments, and hate crimes against Muslims are on the rise. “I think that museums are one of the few platforms where you can have a non-polemic debate about something or learn about other cultures without yelling at each other the way they do on a lot of talk shows,” Hollein said, explaining that he hopes the exhibition will dispel certain misconceptions and prejudices.

While some mannequins wear hijabs, others do not, and there are no face-covering burqas on display. Of the decision not to include them, D’Alessandro said, referring to her show, “It is about design, it’s about celebrating contemporary Muslim fashion. I think that it has to be pointed out that we are celebrating artistry.”

Installation of “Contemporary Muslim Fashions” at the de Young museum. Abayas and handbag by Oscar de la Renta, John Galliano, Marchesa, and Stephane Rolland.

COURTESY OF THE FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO/JOANNA GARCIA CHERAN

Reina Lewis, a professor of cultural studies at London College of Fashion at the University of the Arts London, was a consulting curator on the exhibition. She, too, views the show as a way of sparking dialogue. “Fashion is a fabulous conduit for a whole series of important conversations,” Lewis said. “Sometimes, precisely because fashion is trivialized as frivolous, talking about clothes is a good way to open conversations with people or groups you might not usually talk with, and about topics that might seem delicate.”

Hollein was also struck by the global momentum of what’s been termed modest fashion—that is, clothing that is less revealing, looser fitting, and worn either for religious reasons or personal preference. These days, modest fashion is everywhere, and from Dolce & Gabbana to Macy’s to The Modist, a luxury e-tailer modeled after Net-a-Porter, Muslim consumers spent an estimated $254 billion on apparel in 2016. With 43 percent of the world’s Muslims under 25, Muslim women—those who cover their heads and those who do not—are no longer being ignored by the fashion industry.

Author Shelina Zahra Janmohamed, who coined the phrase “Generation M” for Muslim millennials, and who contributed to the exhibition’s catalogue, has said that many young Muslims are embracing their religion and see dressing in Islamic fashions as a way to redefine cultural narratives.

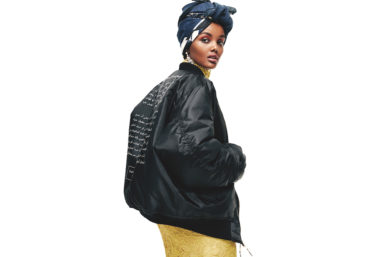

Céline Semaan Vernon (b. 1982, Lebanon) for Slow Factory (est. 2012, United States). “US Constitution and First Amendment” flight jacket and “Banned” scarf (worn as turban), 2017. Screen-printed polyester (jacket); screen-printed cotton and silk (scarf).

SEBASTIAN KIM/COURTESY THE FINE ARTS MUSEUM OF SAN FRANCISCO

To that point, the de Young show delves deeply into what Islamic style is and isn’t. Here it’s fashion-statement abayas, the language of Tehran street style, and female athletes wearing Nike’s sports hijab. It’s the voice of artist and musician Mona Haydar, a new face of “Muslim cool.” In “Wrap my Hijab,” Haydar, a Syrian-American artist from Flint, Michigan, sings with pride about wearing a hijab, and feminism. Her video, which is on display, has received more than four million views on YouTube and has drawn comparisons to Beyoncé’s visual album Lemonade (2016).

Some of the fashions on display are political. Céline Semaan, of the Brooklyn-based Slow Factory, has called her design of a Navy flight jacket with the U.S. First Amendment written in English and Arabic printed on its back, a piece of fashion activism.

Seemingly worlds away, the previous fashion exhibition at the de Young, in 2017, was “The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion, and Rock & Roll,” which explored the counterculture that blossomed in the legendary San Francisco summer of 1967. D’Alessandro, who’s curator in charge of costume and textile arts at the Fine Arts Museums, found a surprising number of similarities between the two presentations. “ ‘With Summer of Love,’ the counterculture was using dress as a means to express their personal point-of-view, their political affiliations, their social affiliations,” she said. “I think that both these projects are really interesting in the role of fashion as a signifier that goes beyond just style or trend.”

The powerful social media portion of exhibition, curated by Camerlengo, an associate curator of costume and textile arts at the Fine Arts Museums, tackles some of the more political aspects of the subject. This section includes coverage of the French burkini ban and work from the Iranian political-fashion blogger Hoda Katebi of JooJoo Azad. Among the 40 photos on view are images from Detroit street photographer Langston Hues, Iranian artist Shirin Neshat, and Moroccan artist Hassan Hajjaj. The voices of digital influencers and ordinary Muslim women come to life via Instagram feeds.

Installation view of “Contemporary Muslim Fashions” at the de Young.

COURTESY OF THE FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO/JOANNA GARCIA CHERAN

Nabila Siddiqi, who attended the exhibition with her mother Naila, who wears a hijab, and her aunt, Najia, who does not, was deeply affected by the show. “In an increasingly unwelcome world, it felt amazing to see Muslim women being recognized, simply for their courage of being themselves,” she said.

Najia, who grew up in England and who has lived in Chicago for the past 28 years, shared that sentiment. “This is the first time I’m seeing something like this and that’s astonishing to me. It’s taken a long time to get to this point where you can freely put on something like this without some sort of backlash.” Her sister Naila, who wears a hijab, said, “Hopefully it will show that Muslim women are not oppressed. [Wearing a hijab] is a choice.” She said that she chooses to because “I feel like I have a lot to be thankful for which is why I follow the rules of our religion.”

For Nabila, a lawyer and mother of two young children who was brought up in the U.S. and said she still sometimes feels like an “other,” the exhibition was empowering. “It just made me so happy that the rest of world might see Muslim women as we really are, not as they paint us to be,” she said. “Muslim women are lawyers and doctors and architects and teachers, and of course, extremely fashionable.”

[ad_2]

Source link