[ad_1]

She was called the “Angel of the Confederacy” and Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí, of all people, was nearly chosen to create a statue of her in Virginia, the state with the most Confederate monuments in America. It would have been one of just a handful of statues of women who have been construed by some as Confederate heroes, and it would have stood on Monument Avenue in Richmond, not far from a controversial monument to Confederate States Army leader Robert E. Lee that is now slated for removal.

The female figure in question was Sally Louisa Tompkins, who operated a Richmond hospital during the Civil War that regularly welcomed Confederate soldiers. The high success rate of treatment at Robertson Hospital caused Tompkins’s star to rise. So esteemed was her enterprise that, in 1861, when Confederate President Jefferson Davis closed all private hospitals, he allowed hers to remain open by commissioning her as an unassigned captain in the Confederate Army, making Tompkins the only woman to hold that title. High-ranking Confederate soldiers fawned over her—one aide to Lee wrote in a letter that she was “an angel on earth—or should I say she is a true woman.”

Tompkins was one of many Confederate figures who neither promoted slavery nor outright decried it. (Another was Lee, who called slavery “a moral & political evil,” despite owning slaves.) In the book Captain Sally: A Biography of Capt. Sally Tompkins, America’s First Female Army Officer (2018), historian Thomas T. Wiatt claims Tompkins was an apolitical person, writing, “there is no hiding the fact that Sally was pro-Confederate, but she was a nurse first.” Wiatt later notes that, toward the end of the war, even when it became clear that the end of the Confederacy was nigh, Tompkins herself owned slaves. During the war, she paid them wages in order keep them from “running off and joining the Union Army since a ‘colored’ Union soldier would make much less,” Wiatt writes.

That would seem to make Tompkins, who died in 1916, a strange subject for a work by Dalí, whose dreamy Surrealist tableaux rarely had any real-world referents. Making a statue of Tompkins could be construed as some kind of political gesture: when he started working on it during the mid ’60s, at the height of the civil rights movement, it’s unlikely that Dalí would have been unaware of what it would mean to monumentalize a figure from Confederate lore. But it is unclear, based on local coverage from the time, how much Dalí knew about Tompkins’s history, or how much he cared.

The road to Dalí’s would-be monument kicked off in 1965, after Richmond officials came up with a new plan to honor the Confederacy’s role in the Civil War. The last time the city had erected a Confederate monument was in 1929, when Richmond built a statue of Matthew Fontaine Maury, a Confederate Naval Officer who, before the Civil War, proposed a plan to resettle slaves from the United States in the Amazon, in a failed attempt to rid his home country of slavery. (When that strategy didn’t work, Maury tried to force Brazilian leadership into accepting American colonialism in the form of trade; that also failed.) It was time for something new, local politicians thought. They issued a report calling for seven commissions for Confederate monuments, none of which were ultimately executed.

In January 1966, Roland Reynolds, a young member of the Virginia family that then owned Reynolds Metals, makers of Reynolds Wrap, convened a group of experts to discuss a monument to Tompkins that would make use of aluminum foil produced by his family’s company. According to the American Civil War Museum, that committee included a Civil War expert, a Confederate Museum house regent, two Virginia politicians, and a representative of the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s president general. The Reynolds family had supported Dalí’s art in the past, and two months after the committee’s meeting, Reynolds was telling the press that the Surrealist had “expressed interest in” taking on the commission.

Local press greeted the news enthusiastically. “Salvador Dalí may be one of the world’s greatest artists, but he’ll have to prove it if he wants to do a statue of Capt. Sally Tompkins,” a reporter for the Richmond Times-Dispatch wrote.

To that committee Dalí offered his own out-there concept that was in line with the artist’s predilection for Freudian weirdness and perplexing imagery drawing on art-historical tradition. His concept recast Tompkins as St. George, who, according to Christian mythology, rescued a princess from a dragon that demanded payment in the form of human flesh. Reynolds Metals said it would give 1,000 pounds of aluminum to the project, which Dalí wanted to be colored a garish shade of pink. According to Dalí’s design, Tompkins’s shield would have a Confederate flag on it, and the 20-foot-tall sculpture would be sited atop an enormous model of Dalí’s finger.

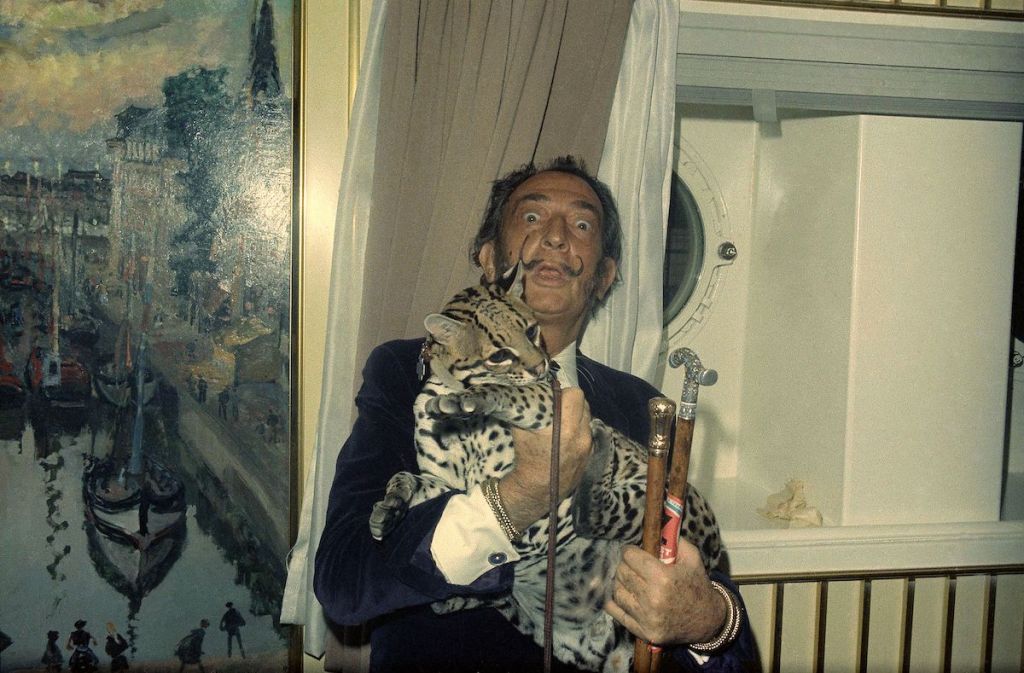

But when it came time for Dalí to reveal that concept, as well as two other more conservative versions in which the figure of Tompkins cares for an ailing Confederate soldier à la the Pietà, a mysterious emissary named “Captain” J. Peter Moore appeared in his place, along with the artist’s pet ocelot, Babou, and a female companion. “This is an obvious extension of tradition—not just a crazy hamburger nouveau riche idea,” Moore told the press, adding that the work would “pay tribute to America this way—a kind of Statue of Liberty, you know.”

Locals did not take kindly to such an avant-garde vision for the monument. One member of the committee, sensing a kind of narcissism in the outré concept, quipped, “Are we erecting a monument to Sally or Dalí?” By April 1966, the Richmond Times-Dispatch was reporting that Dalí was “not on the best of terms with the group of Richmonders attempting to encourage the erection of a statue to Captain Tompkins.” Reynolds died after walking into the propeller of an airplane, and Dalí’s project perished along with him.

Dalí’s politics have never been easy to discern. He flirted with fascism—he once claimed that Hitler “turned me on”; he was friends with Wallis Simpson, a Nazi sympathizer; and he professed admiration for Francisco Franco, the Spanish fascist dictator. André Breton even expelled Dalí from the Surrealist group after the artist painted The Enigma in Hitler in 1939. But some art historians have claimed that Dalí was merely using fascist statements to shock—or trigger, in today’s parlance—his leftist colleagues. “For Dalí, [Surrealist activity] was inevitably an end to itself and therefore in some way inoculated against the real world,” Dawn Adès, a British art historian, once wrote. “Hitler was not in his view different in kind from William Tell or his nurse, because all that mattered was their existence in his mind as dream subjects.”

What did it mean, then, for Dalí to conceive a Confederate monument? Was he promoting Confederate ideology, or was he making fun of it? Was this just another dream vision, or could it have signified something more? To those questions, you might add another: Does it even matter what Dalí was trying to say when his subject was integral to a legacy partly responsible for systemic racism that still survives in the United States? Monumentalizing a figure such as Sally Louisa Tompkins, who has been praised by some Southerners for kindness and heroism, is also a way of upholding the ideals of Robert E. Lee and the Confederacy—which, as Adam Serwer has written in the Atlantic, place “tribe and race over country” and in a sense helped “form the core of white nationalism.”

Dalí’s sculpture of Tompkins was never realized, but her image is still memorialized in the form of a stained glass window at Richmond’s St. James’s Episcopal Church. Art historian Kevin Concannon has written, “She is portrayed as Richmonders prefer to remember her, with her medicine bag, her Bible, and her hospital at Main and Third.”

[ad_2]

Source link