[ad_1]

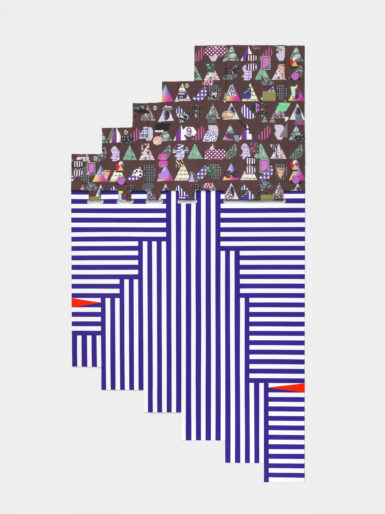

Installation view of “Ruth Root” at the Carnegie Museum of Art

BRYAN CONLEY/COURTESY CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF ART

Not long ago, one of Ruth Root’s friends told her that she had spotted a user of the dating-app Tinder posing in a photo next to one of her paintings. The artist’s reaction, she recalled with a laugh: “You should definitely go out with this person!” I concur.

That someone would pose with one of Root’s pieces can only be the sign of a great potential partner. Her paintings are, after all, some of the most joyful, generous artworks being made today. Composed of intriguingly shaped panels, riotous patterns, and fabric printed with wry found images, they are also master classes in balancing disparate competing forces—models of democracy—and they wear their unusual sophistication with a charming lightness.

Root, 51, has been at it for more than two decades, showing steadily at a handful of galleries, and she has just recently begun to step into the museum world—first with a solo outing at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, in Ridgefield, Connecticut, in 2015, and now another that runs at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh through August 25.

Ruth Root, Untitled 2, 2019, which is bedecked with images of the artist’s tools. Click to enlarge.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ANDREW KREPS, NEW YORK/EPW STUDIO/MARIS HUTCHINSON

In early March, Root was finishing work on her Carnegie show when I visited her in the Tribeca section of Lower Manhattan, in a studio jam-packed with swaths of fabric, a sewing machine used to make sails, a grommet press, and all the brushes, rolls of tape, and other items that one typically finds in a painter’s workspace

Images of many of the exact same tools were printed in a dense field on purple fabric that would soon end up in one of her new paintings. “These are all the materials that are in the show,” she said, comparing the array of photos to the brand-name-covered clothing that characters wear in the absurd futuristic world of the 2006 film Idiocracy. “That is just what this has become—it’s like the means of production,” she said.

In the work she made with that tool-printed fabric, the textile covers a flexible panel whose bottom section is threaded through a long, thin hole in a gray second panel, like a belt going through a buckle. Most of the 10 untitled works in the Carnegie Museum show have a similarly ingenious construction—two halves joined by one or more loops, one part supporting another.

They start as drawings, which eventually become templates that can be cut into panels. Root prints her fabrics through the website Spoonflower with designs she makes on Photoshop. “I’m just using it very folk artist-y,” she said. “I just watched all the demos on YouTube, and I have a best friend that uses it also and is an artist.”

Root evinces such a steady, easygoing presence, both in person and in her art, that I was surprised to hear her say, “It was a hard show for me. Sometimes they’re easier but something about this was really hard. It’s almost like because every painting fits into a little bit of a puzzle.” The works she has conjured connect in diverse ways—oddball shapes and patterns and colors recurring here and there, rhyming across space.

Ruth Root, Untitled 8, 2019. Click to enlarge.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ANDREW KREPS, NEW YORK/EPW STUDIO/MARIS HUTCHINSON

Part of the issue, Root said, was that she wanted the paintings “to relate to the Carnegie’s collection, but I didn’t want it to be so didactic or obvious.” She wandered the museum photographing art—by Sol LeWitt, Joan Brown, Lee Bontecou, Eva Hesse, and many more—and printed those images on fabric alongside portraits of artists like Lorraine O’Grady and Ana Mendieta, plus Anita Hill and Christine Blasey Ford as well as a slice of pizza and monsters from a television show watched by her son. It feels like a self-portrait by other means—an effervescent, unfiltered constellation of all the people and images that come to define and inspire a life. “The funny thing is, when I try and make sense of it, it doesn’t,” Root said. “It’s like a non-verbal way of relating my work to the history of painting.”

Another piece includes reproductions only of eyes from artworks owned by the Carnegie. They stare every which way, just like those of everyone who visits Root’s exhibition and tries to take in her delirious menagerie of references. “I’m really interested in how images relate to one another and travel through people,” the artist said.

Some paintings also explode with color in portions that she has hit with spray paint, and they come close to entering full-on Op-art territory. “At first, it was like: this is going to make the stoners crazy!” Root said of one such piece, adding that she later got used to its visual mania. (I suspect the stoners will still enjoy it.)

Elsewhere, though, Root is restrained, as in an 11-sided piece that is all white. It’s a tender work, a touch like a Robert Ryman, and its spareness lets her clever method of interlocking panels become the focus, recalling the work of another master of sui generis shapes: the veteran Chicago-based artist Diane Simpson.

Discussing her artistic influences, Root touched on Nathalie du Pasquier, Nicola L, Miyoko Ito, Sonia Delauney, and Chris Burden, whom she once saw lecture at the University of Miami when she was a teenager. (Her mother was studying architecture there at the time.) “It blew my mind—that this was a way of thinking,” she said of Burden’s harrowing performance work. She left with a realization: “There’s more out there in the world.”

Root’s art imparts a similar sense of wonder—freely borrowing images and patterns from throughout the history of art and design, and marshaling that material into something that is new and luminous and unusual in the best way, like a friendly-looking stranger you spot and instantly are sure you would like to get to know.

[ad_2]

Source link