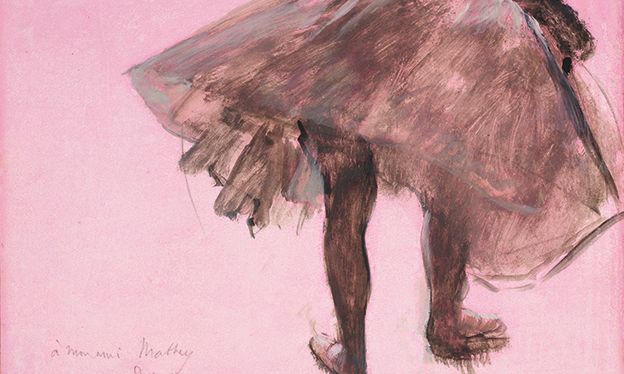

Edgar Degas’s Dancer Seen from Behind (around 1873) features in the RA show

© Collection of David Lachenmann

After decades of blockbuster shows, eye-watering auction sales, and books and films by the boatload, is there anything left to say about Impressionism and the Impressionists? A new exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA), called Impressionists on Paper, is suggesting there is. As its title indicates, this survey of the Impressionists’ pioneering works on paper, jointly curated by the RA’s Ann Dumas and the art historian Christopher Lloyd, will look at how the artists fundamentally changed what was considered acceptable in a finished work of art.

Dumas, who also co-curated the RA’s 2020 Picasso and Paper exhibition, says that the habits and instincts of Impressionist painters engineered a shift in the status of work on paper as opposed to canvas and wall painting. “In the past, drawings tended to play a secondary role: preparatory studies and that sort of thing. But in the period we cover—the second half of the 19th century—the portability of materials, colours, pastels and so on really supported the Impressionist aesthetic of wanting to capture life on the wing, and to capture spontaneity.”

Working on paper “allowed artists to be very experimental”, Dumas continues. And in breaking with the 19th-century tradition of historical and narrative painting, the Impressionists took advantage of new formats and advances in manufacturing techniques to create extraordinary new work, from Edgar Degas’s drawings of dancers and Odilon Redon’s highly coloured dream images, to Claude Monet’s pastel studies of cliffs at Étretat and Georges Seurat’s “fusain” drawing Seated Youth (1883) made using black conté crayon.

Dumas points out that Monet’s brother Leon was a research chemist who worked on the development of cheaply produced dyes that triggered the upsurge of interest in colour and optics in the second half of the century. It all, Dumas suggests, reinforces Impressionism’s foundational role in the march of 20th-century Modernism, as it set out on its path to find pure form and colour. “The much bigger point,” Dumas says, “is that out of this freedom, capturing colour as a means of expression really took over from subject matter in importance.”

These days, most of the works are in fragile condition: low light levels are required to display the pictures, and many of the pastels are in a delicate, friable state. As a result, institutions are often reluctant to lend paper works. Therefore, Dumas says, the show is a unique opportunity. “Drawings and works on paper are not normally on display in the collections they belong to. If you want to see a Degas drawing at the British Museum, for example, you have to make an appointment to go and look at it. So, in our show, people will see a lot of work by famous artists that they won’t have seen before and may not see again.”

• Impressionists on Paper: Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 25 November-10 March 2024