[ad_1]

If Minimalist artist Donald Judd is known as a writer at all, it’s likely for one important text—his 1965 essay “Specific Objects,” in which he observed the rise of a new kind of art that collapsed divisions between painting, sculpture, and other mediums. But Judd was a prolific critic, penning shrewd reviews for various publications throughout his career—including ARTnews. With a Judd retrospective going on view this Sunday at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, ARTnews asked New York Times co-chief art critic Roberta Smith—who, early in her career, worked for Judd as his assistant—to comment on a few of Judd’s ARTnews reviews. How would she describe his critical style? “In a word,” she said, “great.”

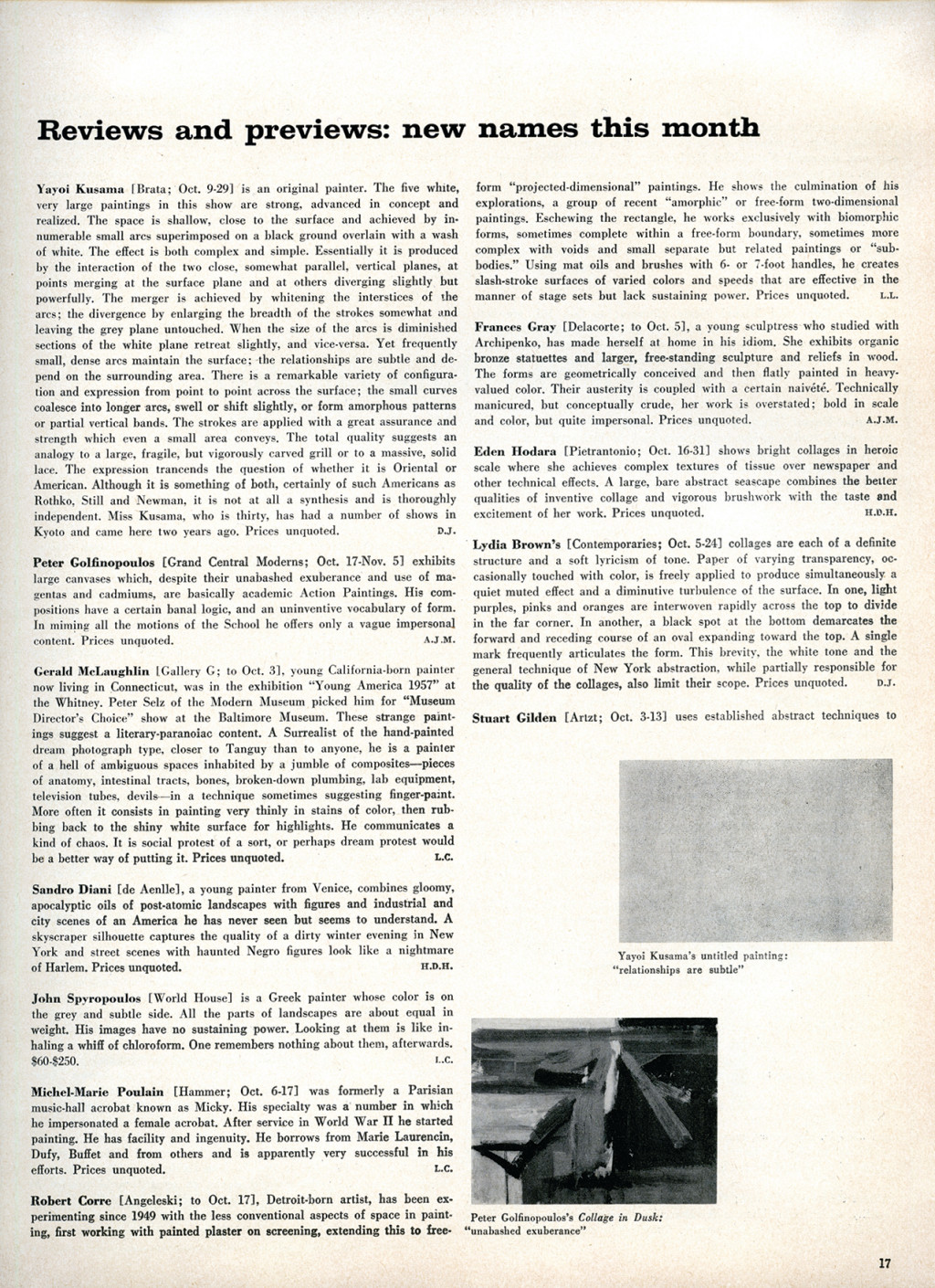

Yayoi Kusama is an original painter. The five white, very large paintings in this show [at Brata gallery] are strong, advanced in concept and realized. The space is shallow, close to the surface and achieved by innumerable small arcs superimposed on a black ground overlain with a wash of white. The effect is both complex and simple.

The Kusama [review] is classic Judd. It’s him recognizing and arguing for something he feels is new. He has this understated exultation for her. He writes, “The strokes are applied with a great assurance and strength which even a small area conveys.” You know that’s a big compliment.

In large oils of Arizona landscapes and smaller watercolors, [Richard] Artschwager uses a quick spiked stroke, elongated and communicative of abbreviation, a clipped dissolution. There is a sensitivity immanent in the stroke, especially when the technique is used in the sparse context of two effective watercolors of dunes. The more abstract watercolors are less telling, too casual and airy.

You can learn a lot about him from reading his reviews. You get this great template for criticism—for ideas about short reviews, tone, and pace, and for looking and writing about looking. In the beginning, he had this formula—describe and judge, describe and judge. If you’re interested in criticism, it’s such a great place to see it in its most essential qualities—that is, making a case for an opinion.

[Harold Altman’s] technique of creating planes with fine parallel strokes is derived from the Cubist etchings of Villon. Altman uses the method with exceeding finesse and much about the configurations the planes assume is personal.

ARTnews at the time was a bastion of Abstract Expressionism. From ’58 on, he’s very uncomfortable with what’s happening, in terms of what he saw as the dilution of this style by a younger generation, who he thinks are following it too devotedly and in a way that starts echoing Cubism. Judd said he was always left alone [at Arts magazine, where he began writing for its editor, critic Hilton Kramer, after he stopped contributing to ARTnews], and ARTnews likely had more editing, which he probably wasn’t crazy about.

Joseph Stella retained a lifelong interest in portraiture fundamentally at odds with the methods of his well-known bridge and city paintings. … A profile Self-Portrait characteristically combines such elements as the sophisticated line and flattened, gradated, shading of Stella’s coal mine drawings with the naïve anatomy renderings of a primitive, and a conspicuously textured wash in the background. Stella accepted too simply the idea that the span of expression is that of a technique, yet, at the time, even the attempt to unify such a range was a contribution.

He’s so confident that his negative opinions, at least in these reviews, are never really mean. Sometimes, he’s sarcastic in an opening line. But he really gives people their due, particularly in the Joseph Stella one, where he’s offering different opinions about different kinds of work in the show. … Judd worked in a much different time, when art’s linear progress had a credibility that it doesn’t today. This moment calls for a different kind of criticism.

A version of this article appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of ARTnews, under the title “Describe and Judge.”

[ad_2]

Source link