[ad_1]

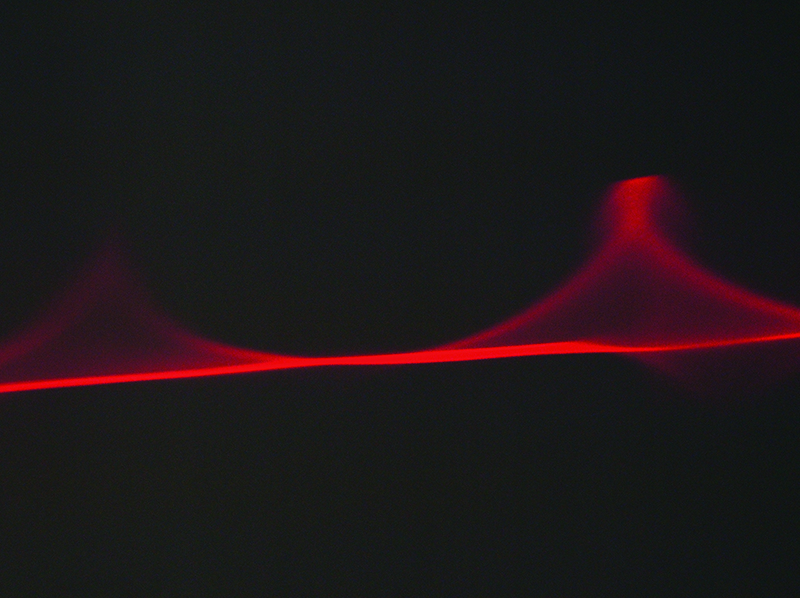

Robert Whitman, Wavy Red Line, 1967.

©ROBERT WHITMAN/COURTESY PACE GALLERY

‘This department has had the exhibits examined and I am of the opinion that exposure of the eyes to the beams can be dangerous to the eyes. You are, therefore, directed to discontinue the use of the laser permanently.” So wrote the Commissioner of Health for New York City in a letter to Pace gallery in 1967, condemning a show by Robert Whitman that could rightly be said to have lit up the art world.

The location was an old Midtown home for Pace, and the exhibition was “Dark,” a gathering of works by an artist then associated with Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) but also so much more. Now, one of Whitman’s E.A.T. works—with the laser that incited official governmental protestation—is back at Pace in Chelsea, with some of the “so much more” in addition.

Robert Whitman, Great Lakes, 1996.

TOM BARRATT/©ROBERT WHITMAN/COURTESY PACE GALLERY

For “61,” a career-spanning survey covering more than six decades of Whitman’s work and play, some two dozen pieces range from video and sculpture to painting and performance, with lots of blurring in between. Giant sculptures seeming to contain blue water in brown paper bags (Great Lakes, from 1996) greet gallery-goers at the start, and from there follow works like the laser-abetted Wavy Red Line (1967), the early video installation Shower (1964), and a piece of string (Untitled, from 1957) suspended from the ceiling with nothing more or less to show for itself or its intentions. Accompanying all of those pieces and more is video documentation of what Whitman is best known for: performance-theater pieces dating back to the early 1960s, when he was active in the midst of early Happenings and makeshift shows of varying kinds in downtown New York.

Common among all of the art on view is an allegiance to absurdity and intuition. “Didn’t they tell you you’ve come to the wrong guy?” Whitman said, when queried about the rationale behind his work. “I hate talking about my stuff. When you come back years later, you realize that what you said about it the first time was a bunch of bullshit. The key thing about any art: once I stop thinking, I got it. Like Dave Brubeck put it once, when he was talking to somebody about playing unusual rhythms: ‘If you have to count, you’re fucked.’ ”

Robert Whitman.

HOLLISTER LOWE

Whitman was at Pace a few weeks back to entertain questions about a career that has put him at the forefront of different movements and scenes. Certain lines of inquiry were non-starters—but not all. “One of the things I could talk about is that one of the materials I work with is time,” the artist said. “I tend to want to try to treat it like any solid object, a physical thing. The problem, of course, is you have to live long enough.”

One offering in the show that stares down time directly is Dressing Table, a video work presented in its original form from 1964 as well as a remake from earlier this year. The star of them both is Susanna Wilson, an old friend of Whitman’s from the Lower Manhattan milieu. Married for a time to the artist Walter De Maria, Wilson (then Susanne De Maria) got to know Whitman when he was wed to the dancer Simone Forti. “The four of us were really close. We used to make dinners together and travel together,” Wilson said. “Simone would make the most beautiful simple dinners. I always appreciated how easy it was for her to poach a fish.”

One time they traveled to a small town out of the city, on a trip during which De Maria recorded his cryptic audio piece Cricket Music (“We had a reel-to-reel tape recorder and he set it out in the field all night,” Wilson said) and Whitman shot Dressing Table, with Wilson as the woman who, over the course of a silent spell, slowly applies makeup and earrings before eventually aggressively covering her face with paint. “I would do anything for an artist,” said Wilson, who also worked with Andy Warhol and Joseph Cornell, among others. “Having done other things with [Whitman], I knew he was like a poet, that things would be slightly abstract and the viewer would be able to interpret it in different ways. I thought of it as an abstract painting.”

Robert Whitman, Dressing Table, 1964 and 2018.

©ROBERT WHITMAN/COURTESY PACE GALLERY

“One of the things I’ve realized is how brave people were, and how generous,” Whitman said of a kind of free-flowing collaboration that was common in New York at the time. “There was never any question. “Like ‘9 Evenings’ ”—the fabled 1966 series of “theatre and engineering” performances at the Park Avenue Armory for which Whitman was an organizer—“there must have been 100 people involved. There wasn’t money to pay anybody. People who got paid were professionals, like riggers, union guys. Everybody else just showed up. I’m looking to see if that’s going on in some of the little art enclaves now, like in Brooklyn, to see if they have that same spirit. I hope they do.”

The oldest work in the show, which runs through December 21, is the untitled string, which Whitman conceived as a student at Rutgers University in 1957. “That piece wouldn’t exist if Lucas hadn’t seen it,” Whitman said of the artist Lucas Samaras, who glimpsed it a few years later at his apartment in the Bronx and took a liking to it.

Another work from that same early year is Red Square, a tattered construction of wood slats painted red, like a frame with nothing inside. “I would leave stuff around to get beat up, to show age,” Whitman said. So he was, even at the beginning, working with time? “Yeah, but I didn’t know it—I won’t take responsibility for it!” he said, with a laugh.

More elaborate works include Inside Out, a film installation from 1963 that Pace founder Arne Glimcher said he believes may be the first multi-screen artwork ever made, and Window (also 1963), which broadcasts filmed footage of a woman cavorting in the woods behind a window built into a sculptural wall. Similarly, Shower, from 1964, features the image of a woman cleaning herself in a stall with a water pump installed.

Robert Whitman, Window, 1963.

©ROBERT WHITMAN/COURTESY PACE GALLERY

The most technically complex piece is Wavy Red Line, the laser installation that shoots a moving beam around by way of a motor. “I wanted to draw a red line around the room and have it undraw itself,” Whitman said. “The Board of Health got scared and shut it down.”

“They thought it would make people go blind,” Glimcher recalled. “We had people from Bell Labs working with us and they guaranteed us it was all fine.” But such assurance might not have mattered, in any case. “We were so committed that we would have showed it even if it blinded everybody!” Glimcher laughed. “There was a different sense of purpose at that moment. You never thought of an audience to buy these things. You just were forging ahead with the history of art.” (It’s a notion worth pausing to consider: a gallerist who blinds his audience with the art he shows.)

Glimcher called Whitman “a great unsung genius” for all the different kinds of work he’s done. “He processes the world in a different way. He sees absurdity as reality. Things beneath notice, he amplifies.”

Whitman himself attributed some of that—especially as it has manifested in his theatrical performances and happenings—to a favored source of entertainment going back to his youth. “People don’t understand, at least in this country, the history and tradition of clowns,” he said. “I look at some of these things in the context of clowns—there’s absolutely no reason for some of these things to have occurred.”

His favorite clowning moment was seeing the storied American circus performer Emmett Kelly sweep up a spotlight on a floor with a broom. “The character he had, the ragamuffin bum, was sweeping up a light,” he said. “He can’t do it, but he finally scoops it under the rug—and the light goes out. When I saw that happen, I was thunderstruck. I couldn’t understand why the rest of the people weren’t struck dumb.”

“I mean, for me,” he continued, “time stopped.”

[ad_2]

Source link