[ad_1]

With “Robert Morris: Para-Architectural Projects,” Hunter College’s Leubsdorf Gallery spotlighted a seldom-seen portfolio by a postwar artist whose sculpture and writings helped define the Minimalist idiom of the 1960s and its eventual unmaking in “process art.” Illustrating Morris’s turn toward environmental scales, the show collected seven large-format drawings from 1971 that offer glimpses of what the late artist termed a “fantasy complex” of walkways, observatories, aqueducts, and courtyards. These ink-on-paper renderings chart a vast landscape of open-air structures that sit suspended between architecture and sculpture, movement and stasis.

© 2019 The Estate of Robert Morris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo Stan Narten.

The works belong to a larger series of twenty such drawings that debuted in Morris’s 1971 solo exhibition at Tate Gallery (now Tate Britain). There, the drawings were overshadowed by the main attraction: an assortment of “interactive” sculptures intended to be rolled, pushed, and climbed and balanced on by museumgoers. The show closed after four days on account of visitor injuries.

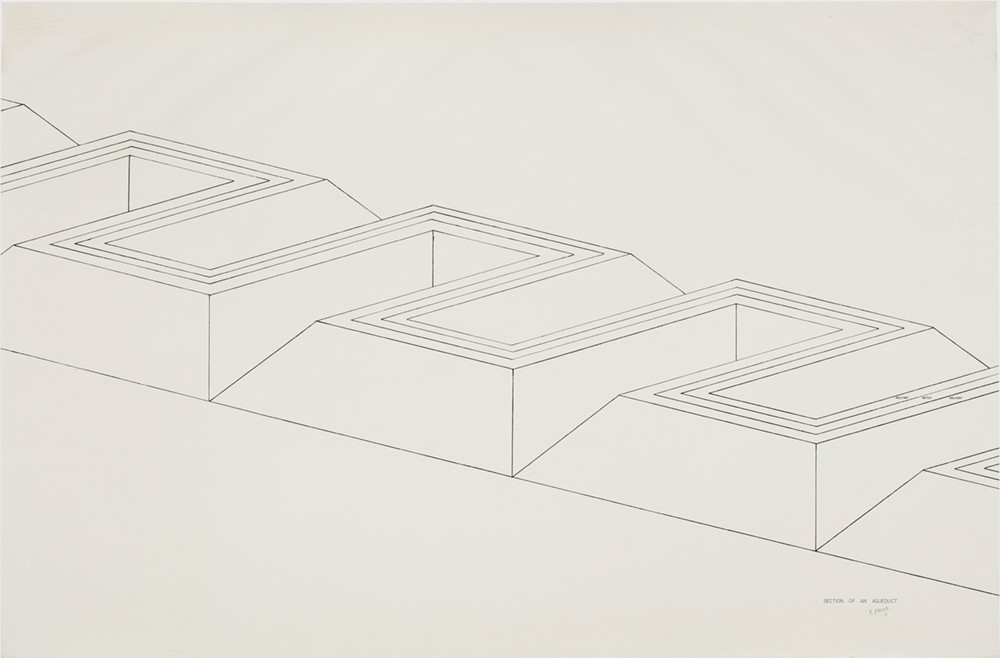

In the Hunter exhibition, only Morning Observatory—Exercise Complex, depicting a large space filled with pools, ball courts, and climbing walls, seemed to nod to the physically interactive playground at Tate Gallery; the rest favored more abstract patterns of use and movement by human walkers, swimmers, and loungers. With most of the drawings foregrounding platforms variously torqued, staggered, and zigzagging, and a couple (such as the serpentine Section of an Aqueduct) featuring flowing courses of water, Morris’s “para-architectural” works would seem to emphasize forward motion—the choreography of pure passage—over and against a sense of built structures as volumetric containers or monolithic forms.

© 2019 The Estate of Robert Morris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo Stan Narten.

The drawings portray only portions and details of the architecture, and thus withhold a sense of the overall size and shape of the “fantasy complex.” How, then, might we place that complex, cryptic as the images are? One can better grasp the artist’s intentions by looking at Observatory, an outdoor circular structure that he first constructed in 1971 for the exhibition Sonsbeek 71, in Arnhem, Netherlands, and that incorporates a component—a pairing of two canted steel plates—featured in the drawing Observatory Markers, Equinox Sunrise–Sunset. (The Sonsbeek iteration of Observatory was temporary, but was followed, six years later, by a permanent version elsewhere in the Netherlands.) Observatory courts comparison to earthworks by artists including Nancy Holt and Mary Miss. But while it is tempting to understand Morris’s para-architecture as a species of Land art, the artist deflected such characterization. He held his work at a peerless distance, asserting in the Sonsbeek brochure, for instance, that Observatory was “different from any art being made today.”

In interviews and essays from the 1970s, Morris suggested that he achieved his needed measure of distance by looking at the landscapes and architecture of South America, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. His article “The Present Tense of Space,” published in Art in America’s January–February 1978 issue, proves a most effective skeleton key for the works in the Hunter exhibition. In that article, Morris praises a “temporal-kinesthetic” model of experience cultivated less by what he terms “normal architectural space” (meaning, perhaps, Western architectural space) than by the “Mayan ball courts, temple platforms, and various observatory-type constructions” of Central and South America.

© 2019 The Estate of Robert Morris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo Stan Narten.

The “para-” that positions Morris’s structures at the edge of “normal architectural space,” and (in his estimation) at a remove from the work of his early-’70s contemporaries, thus denotes a distancing more cultural and historical than strictly formal. In a text accompanying the show, curator Sarah Watson bids us to acknowledge the romanticizing gaze that one might detect in these framing operations, and indeed, Morris’s works rehearse the classic trope of the European or American artist finding egress from formal strictures by reaching beyond the West. Regardless, the drawings here find Morris, like the imagined user of his fantasy complex, in a curious but compelling place of passage: roving, winding, and feeling out the boundaries of a space with no clear terminus.

This article appears under the title “Robert Morris” in the December 2019 issue, pp. 97–98.

[ad_2]

Source link