[ad_1]

Robert Frank.

KATHY WILLENS/AP/SHUTTERSTOCK

Robert Frank, one of the world’s most influential documentary photographers and filmmakers, has died at age 94, according to the New York Times, which first reported the news. A cause of death was not immediately reported.

Frank’s unsparing eye sought to portray things as they really were—unaestheticized, somewhat plain, more than a little dour. Yet, for all the bleakness of his images, both still and moving, Frank, though an immigrant to the United States from Switzerland, was able to capture gritty truths about the American experience that had previously gone undepicted by artists before him.

His 1958 photobook The Americans is a classic—an unsparing, at times even deliberately banal, portrait of class differences and alienation in postwar America. The scenes he shot are the ones that many people encounter every day: men shining shoes, waitresses presiding over luncheonette bars, ladies chatting over diner coffees, crowds on the street. Jack Kerouac, the storied Beat poet who wrote the book’s introduction, famously said that the book “sucked a sad poem out of America.”

There is nothing sentimental about Frank’s images, and in that way, they are unlike the hyper-stylized documentary images by pioneering photographers whose work inspired Frank’s, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, who found himself fascinated by sharp diagonal compositions that are so meticulous, they appear to have been staged ahead of time. The same could not be said of Frank, who preferred matter-of-fact imagery that could speak for itself. Indeed, he found Cartier-Bresson’s famous concept of the “decisive moment” as limiting, opting instead to capture ‘‘some moment I couldn’t explain,’’ as told the New York Times Magazine in 2015. The photographer Diane Arbus once said she appreciated the “hollowness” of Frank’s work.

[See images of Frank’s pioneering photographs.]

The Americans—which features 83 images assembled from the 28,000 that Frank shot while traveling across America on a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship—was published first in France and then in the U.S. It confounded its day’s critics, who had come to expect those “decisive moments” of Cartier-Bresson’s photography—something more refined and glossier than the raw, Walker Evans–inspired aesthetic Frank had on offer. Popular Photography, the preeminent photography publication at the time, famously decried the book’s “meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons, and general sloppiness.” Now, however, it has been embraced. New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl has called it “one of the basic American masterpieces of any medium.”

At the time The Americans was made, photography was not considered a fine-art form by many, and it did not help that Frank’s photographs did not look like art. A few institutions caught on early, however. The Art Institute of Chicago mounted a show of works from The Americans in 1961, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York included Frank in the 1967 documentary-photography show “New Documents,” placing him alongside Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and others.

Robert Frank, Parade – Hoboken, New Jersey, 1955.

©ROBERT FRANK/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL

Many critics have considered The Americans the defining work of Frank’s career. This is, to some degree, a mistake, even though it is an understandable one—his films have largely not been made as available as his photographs. (Laura Israel, Frank’s longtime editor, has been essential in remastering and releasing them. In 2016 Israel also made a film about Frank, the documentary Don’t Blink: Robert Frank.) A full-career film retrospective mounted in 2016 by the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York (with prints from the Museum of Fine Arts Houston in Texas, which owns the archive of Frank’s films and videos) has proven revelatory in this respect.

Starting the year after the U.S. release of The Americans, Frank began producing films that cemented him as one of the important figures in the then-nascent independent scene. His films, too, were done in a blunt and unadorned style, and they furthered themes that had been explored in his early photographs. Made with small budgets, the films tend to emphasize the modest conditions of their making—they are pieced together in a way that feels deliberately slapdash, and their vague narratives tend to feel only partly formed. When critic Nicholas Dawidoff told Frank that he couldn’t understand what the films were about, the artist said, “It was bigger than me. I failed.”

That’s debatable. Frank’s first film, Pull My Daisy (1959), is widely regarded as one of the most important countercultural works of the mid-20th century in America. Co-directed with Alfred Leslie and adapted from part of a Kerouac play, the film focuses loosely on a couple who invites a bishop to dinner at their apartment; their bohemian friends soon come over and start a ruckus. Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, dealer Richard Bellamy, and artists Alice Neel and Larry Rivers appear as part of the cast. Little happens in the film, which is shot like a documentary and features extensive narration from Kerouac.

Frank’s most famous film, Cocksucker Blues (1972), made with Danny Seymour, is a documentary about the Rolling Stones touring America. The photographer had been hired by the band to shoot portraits of its members for the album Exile on Main Street, and he wound up documenting the drug use and group sex he witnessed while the Stones were traveling. Understandably, the band was concerned. Mick Jagger, its frontman, was successful in blocking the film from being released in the U.S. for several years. It has since been screened at Film Forum in New York and elsewhere.

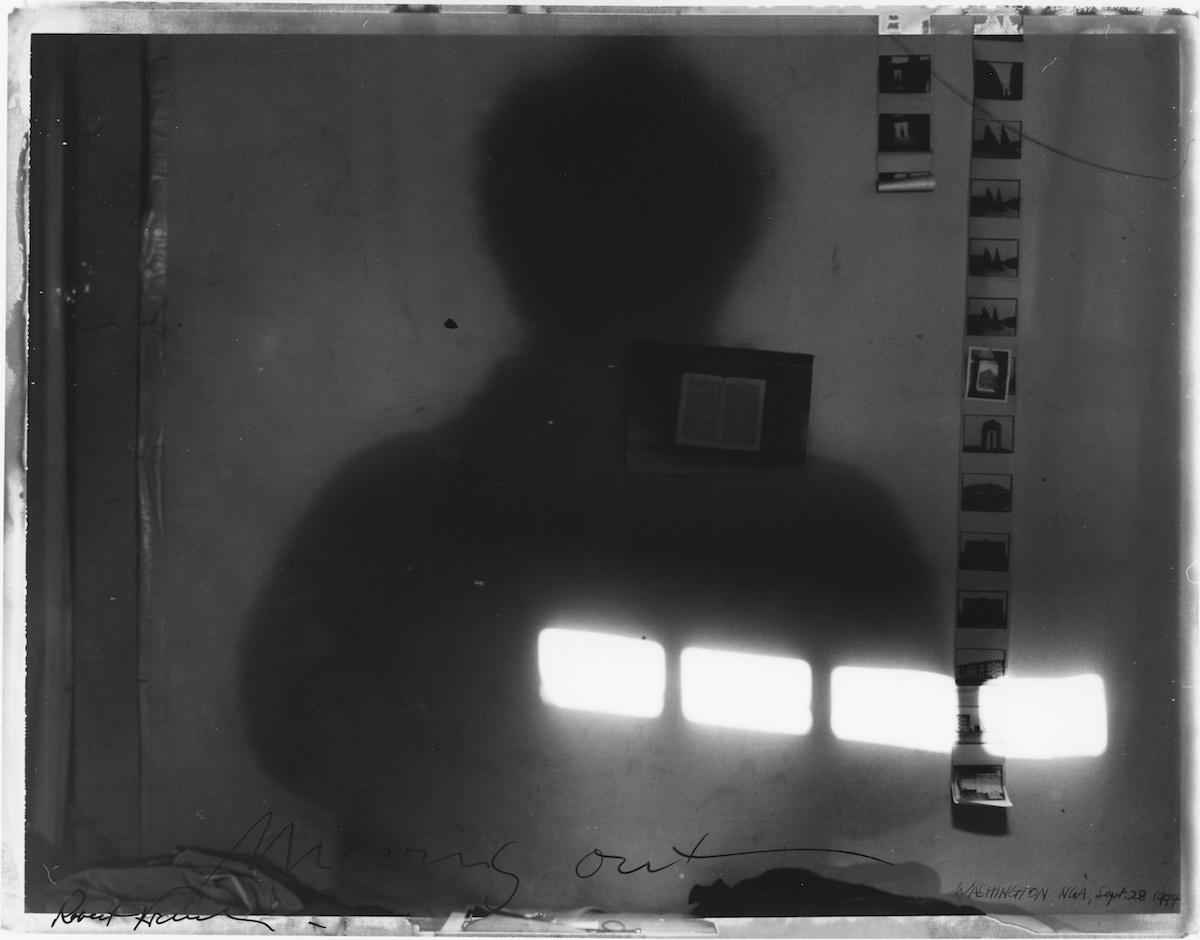

Shortly after Cocksucker Blues, Frank returned to photography, though his images this time around were more affected than they had been in the past. In 1974, Frank’s daughter, Andrea, died at age 20 in a plane crash in Guatemala. Frank began distressing his Polaroids, scratching them out. They charted a shift in his work “from being about what I saw to being about what I felt,” he told the Guardian in 2004. “I didn’t believe in the beauty of a photograph anymore.” Future works would also deal with the death of his son, Pablo, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and died in 1994. His children from his first marriage, to artist Mary Frank, had previously been the subject of his art—they figure prominently in his 1969 film Conversations in Vermont, which was made the year before he wedded artist June Leaf—but never before had his work seemed so emotionally naked.

Robert Frank, New York City, 7 Bleecker Street, September, 1993.

©ROBERT FRANK/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL

Robert Frank was born in 1924 in Zurich. When he emigrated to America in 1947, he began working as a commercial photographer, taking jobs for Life magazine (which was then considered the finest publication for photographic work) and Harper’s Bazaar. He was immediately struck by the strange sensibility of this country. “In Paris you’d see African people on the subway, and they were African,” he said in the 2015 New York Times Magazine interview. “Here in America they are Americans. There is no other place like this.”

Although Frank had been a successful commercial photographer, he wanted to move into documentary work. He began traveling around Europe and South America, and some of his early work figured in “Photographs by 51 American Photographers,” a 1950 survey at MoMA that was organized by influential photography curator Edward Steichen. But in spite of this, Frank was never picked up by Magnum, the pioneering photography collective that included the day’s most important artists working in the medium. According to Frank, photographer Robert Capa, then Magnum’s leader, “said my pictures were too horizontal, and magazines were vertical.”

Still, over the course of his career, Frank achieved widespread fame, and went on to become one of the most celebrated photographers of our time. In 2004, he was the subject of a full-career survey that showed at Tate Modern in London and the Museu d’Art Contemporani di Barcelona. Another survey toured America starting in 2009, making stops at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. And, in 1996, he received the Hasselblad Foundation’s International Award in Photography, one of the highest prizes of its kind.

But Frank often kept himself out of the spotlight. For a large part of his late-career period, he lived in Nova Scotia, far from New York City, where he had initially achieved fame, and he was known to skip out on opening receptions for his biggest exhibitions.

Artists and critics of all sorts have drawn inspiration from him and his aesthetic. His influence can be felt all over, from Danny Lyon’s immaculately composed shots of outsiders to Curran Hatleberg’s unsentimental images taken across America, some of which are now on view in this year’s Whitney Biennial. Artist Nan Goldin, who famously turned her documentarian lens on the Downtown New York scene of the 1980s and ’90s, once said that Frank was “famous because he made a mark.”

It is unsurprising that, as other artists have begun reexamining American identity in a time when it is in flux, The Americans has seen a revival. In 2017 the New Yorker asked eight photographers, including Mary Ellen Mark and Joel Meyerowitz, to pick their favorite images from the book; they each selected different ones, but all brought up the complex ways the tome visualizes forms of oppression inherent in American society.

A less-often-discussed image from the book, but one still as highly effective as the more commonly seen ones, is a vertical picture of Frank’s family in the car on the side of a road in Texas, cropped so that only the artist’s wife and son are seen resting in the passenger seat. It is the final picture in The Americans, and an unusually personal one within a book that seems otherwise disaffected. The photograph’s subject seem exhausted by their travels, and the road in front of them is never shown to us. Frank has brought them on a cross-country search for what it means to be American, one that is seemingly endless.

[ad_2]

Source link