[ad_1]

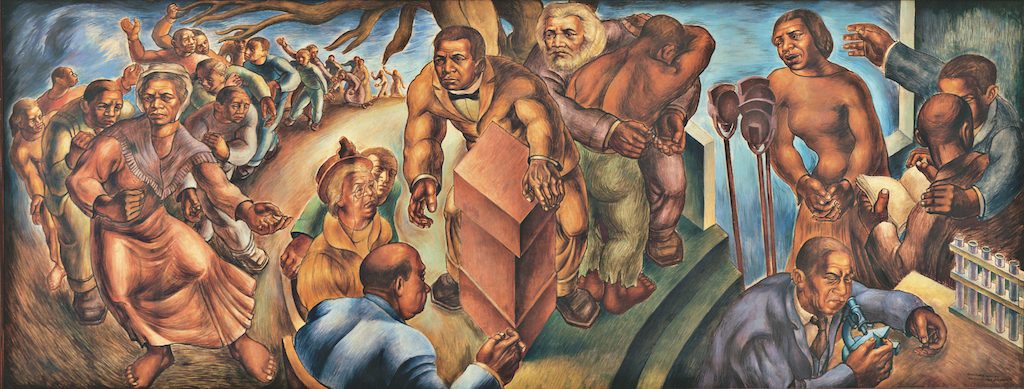

Charles White, Five Great American Negroes, 1939, oil on canvas.

GREGORY R. STALEY/©THE CHARLES WHITE ARCHIVES/COLLECTION OF THE HOWARD UNIVERSITY GALLERY OF ART

Currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York is a retrospective of the artist Charles White, whose richly textured portraits of black men and women have been an inspiration for many, among them his former students Kerry James Marshall and David Hammons. (The show traveled from the Art Institute of Chicago, where it was on view earlier this year.) With that exhibition in mind, as well as a concurrent survey of White and his artistic cohort at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in New York, we have reprinted, below, every review of White’s work that ran in ARTnews during his lifetime. White, who died in 1979 at age 61, was one of the few black artists whose shows were reviewed with some level of frequency by the editors during the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. —Alex Greenberger

“What the Artists Are Doing: Negro Mural”

August–September 1943

A mural by Charles W. White, one of the outstanding Negro artists of this country, has recently been unveiled at Hampton Institute, Virginia, where a round-table discussion of “Art and Democracy Today” was a feature of the occasion. A native of Chicago White painted the mural on a Julius Rosenwald Fund grant and spent many months of intensive research before beginning his work. It depicts his race’s protest against anti-democratic forces as personified in the historical figure of a Colonial Tory shown destroying a 1775 bill prohibiting the import of slaves to America. Here also appear the Negro heroes of the Boston Massacre and of the Civil War and the contemporaries George Washington Carver, scientist; Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, and Leadbelly, all Negro singers; and Ferdinand Smith, labor unionist. The central foreground shows the Negro family in the more socialized world of today. The twenty-five year-old artist was given a free hand both in the execution and the location of the mural. He selected the Hampton Institute for its progressive educational program and its traditional policy of a bi-racial personnel in all departments. The painting is executed in egg-tempera and measures eleven by seventeen feet.

Charles White, Preacher, 1940, tempera on board.

THE DAVIDSONS, LOS ANGELES/©THE CHARLES WHITE ARCHIVES/PHOTO: THE HUNTINGTON LIBRARY COLLECTIONS, AND BOTANICAL GARDENS, SAN MARINO, CALIFORNIA

“Reviews and previews”

October 1947

Charles White [A.C.A.], a Negro painter who has exhibited, taught, and received awards in various parts of the country before his recent New York one man debut, showed oils and drawings in a stylized, semi-abstract idiom akin to such Mexicans as Orozco and Dosamantes. Essentially murals, his compositions often consist of a single figure, starkly projects against the background. Strength and sadness pervaded his work, the grim resignation of WAR WORKER, or the pensive jazz musician of SOLO.

“Reviews and previews”

By Gretchen T. Munson

March 1950

Charles White [A.C.A.] has his second one man show with large pen and ink drawings which are social commentaries on discrimination and the Negro’s fate in past and present history. An undeniably expert craftsman, White stipples and cross-hatches with a delicate pen point to produce the sculpturesque faces which peer from behind bars or barbed-wire fences. Too absorbed with the drama of revolt—potential or actual—the artist denies himself a subtler exploitation of his black and white medium and seeks a hard monumentality which would be more suitable for mural painting, and which actually seems to have been derived in theme and form from Rivera and Orozco. $75-$200.

“Reviews and previews”

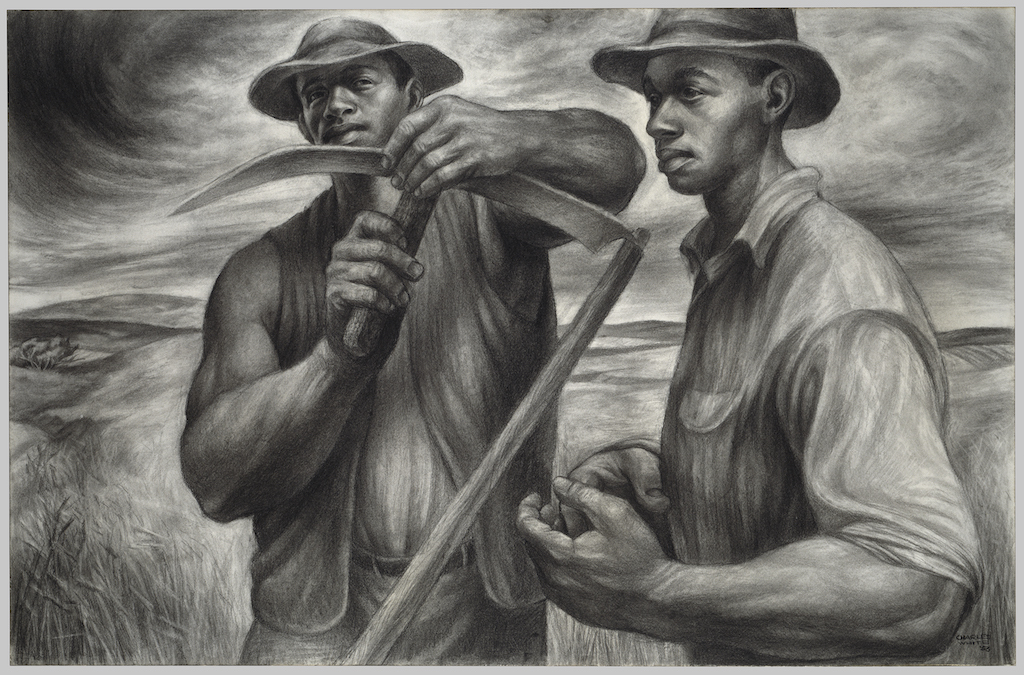

By Larry Campbell

February 1953

Charles White [ACA; Feb. 7-28], whose drawing won a $500 prize at the Metropolitan Museum’s exhibition, makes his latest offering of figures and heads, which are conceived with considerable sensitivity within the confines of a quasi-academic realism. The social implications of his subjects, which are always Negroes, are in expressions—a peaceful, rather indifferent resignation, the way prisoners of war look. But contained within the expression is the tacit understanding that there is a war, and these are its victims if not its prisoners. His best work continues to be his drawings. They are executed in pencil which he reduces to powder, then rubs in with a chamois. The drawing proceeds in different stages: each layer is fixed before going on with the next. The paintings, massive semi-sculptural figures, are not unlike Mexican murals. $75-$350.

Charles White, Harvest Talk, 1953, charcoal, Wolff’s carbon drawing pencil, and graphite, with stumping and erasing on ivory wood pulp laminate board.

©1953 THE CHARLES WHITE ARCHIVES/THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, RESTRICTED GIFT OF MR. AND MRS. ROBERT S. HARTMAN

“Reviews and previews”

By James H. Beck

October 1961

Charles White [ACA; to Oct. 7] is an artist dedicated to the human form and especially the single figure. He is a careful and exacting draftsman in large black-and-white drawings and prints and rarely does he deviate from the anatomical structure of his models while rendering them with precision and accurate chiaroscuro. Charles White is also a romantic and his pictures and their subjects, almost exclusively Negro women, transcend the photographic image to produce a moody world of melancholy, isolation, struggle and his women seem to have a kind of awful primordial self-knowledge. Awaken from the Unknowing shows a robust African, muscled from manual labor, pouring over a table laden with documents and texts as if these sheets contain some concealed mystical power which, once possessed, can free her from her travail. In this large drawing, the scale and the prevailing blackness add to the monumental task of its reader and it stands out as the most striking in the show. Prices unquoted.

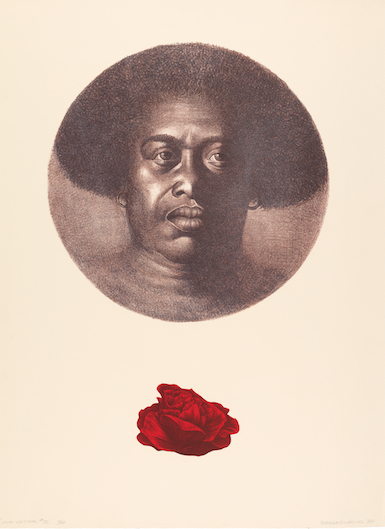

Charles White, Love Letter II, 1977, color lithograph.

©THE CHARLES WHITE ARCHIVES AND THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO/THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, MARGARET FISHER FUND

“Reviews and Previews”

By Claire Nicolas White

April 1970

Charles White [Forum; to April 3] found a series of posters, dating from the Civil War, advertising slaves for sale. Inspired by these he made a series of brown and white drawings, portraits of women and children priced as in the posters, which are an ironic, moving appeal.

“Reviews and Previews”

By Margaret Betz

May 1976

Charles White (Forum): Through purely formal means and sensitive rendering of human faces, White presents an image of his race. Mainly portraits of women, the lithographs and drypoint etchings leave rhetoric far behind. Lilly C. is a quiet face, as are all Charles White’s faces, depicted in the rich dark tones of the drypoint medium. The realistically rendered face and shoulders are caught in a web of crossing lines. The tension between the abstract and the realistic aspects of the work are precisely balanced. Much the same balance worked out in the lithograph Love Letter, 1971, and in the etching Missouri C., 1972, the intense bust profile of a large black woman; the hatching of lines in the latter produces an extraordinary illusion of atmosphere that takes nothing away from the work’s purely abstract perfection. Cat’s Cradle, 1972, perhaps sums up White’s basic concern in the portrait prints of these years. A young boy sits on the ground, legs extended toward us, weaving an enormous cat’s cradle about his hands and feet; the web then expands to envelop the entire surface of the print.

[ad_2]

Source link