[ad_1]

As we mentioned in our last post, the digitization project for the David C. Driskell Archive is in full swing. But right around that time, we hit an impasse. I’ll call it an “impasse” because that’s what it felt like (to me) at the time.

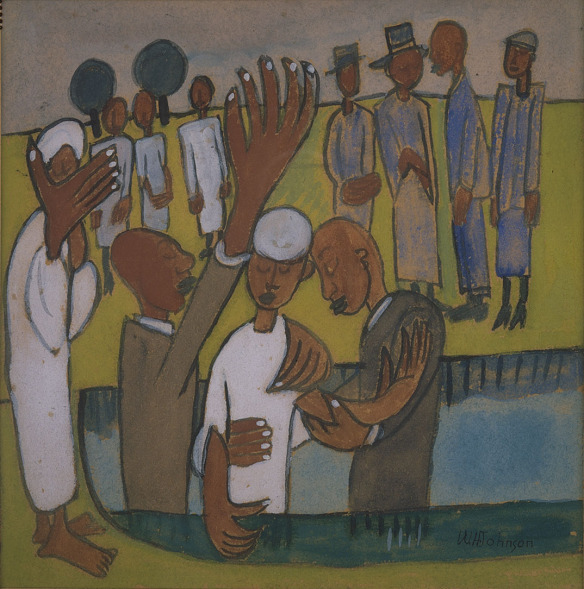

We were handling some requests from researchers for JPEGs of some of our photographs and transparencies to be reproduced in scholarly publications. This led to some critical reflection on the overall quality of the scanned images we had been producing as part of our larger digitization project. It’s misleading to compare an original photographic print source with a scanned digital image rendered on a computer screen. And, there’s a remarkable inconsistency across screens, even in an office like ours, using computers and monitors of similar make and age. But, when we really looked at some of our digital surrogates, we just weren’t satisfied with the quality of the digitized product in relation to the original. Specifically, many seemed to have a haze of sorts over the image and at the same time, oddly enough, the texture of the source was often overrepresented in the scan. It seemed that some scans did a better job of revealing the flaws in a print, than the content of the photo. Crinkles in an old print, even stains on the surface, were showing up better in scans than they did in the originals. This was particularly evident with Instamatic-type matte finish prints from the 1970s that have a bumpy texture you can feel (and see). Scans of photos were often too bright or bleached-out looking and transparencies too dark or dull. We thought we could do a better job of representing our archives.

One of the more intriguing aspects of working in an archives associated with a museum or gallery is the intersection of two perspectives on (re)presentation; one deriving from the art world and the other from the archives world. Museums and archives are both, for all their differences, memory institutions engaged in curation. Curatorial decisions are part and parcel of this and every digitization project. How will we best represent our collections? How will we tell the story of David C. Driskell’s legacy and the Center that bears his name?

I’m a neophyte in both of these worlds but as an aspiring archivist I try to bring the values of the profession to my work. So my perspective is that we should produce the most faithful representation of an object in our collection. But, as we began to think more about why we were digitizing—which is ultimately to tell Professor Driskell’s story, which is also the story of how African American art came to be recognized, appreciated, collected and taught about—we knew we had to produce better images for the scholars who will continue his work for future generations. Thus returning to the idea of curation as it pertains here, we need to present quality images that are not only more accessible in digital form but that genuinely encourage teaching.

Without dwelling on technical details here, what I discovered in the course of my research on the topic is that the mostly right-out-of-the-box settings we were using on our Epson scanner weren’t producing the results we needed to tell our story. But, we needed to find a range of settings that could be applied consistently across material, so that we weren’t changing settings for every image. It was a journey, but through consultation with our digital preservation advisor here on campus, reviewing FADGI guidelines (http://www.digitizationguidelines.gov/), Epson’s SilverFast 8 software manual, and writings and discussions across the web, and extensive testing, we made some progress.

First of all, we needed to properly calibrate our scanner for both reflective and transparency scanning. Additionally, minor adjustments to other settings in SilverFast can produce a better scan; one that is more faithful to the image than its imperfect representation as a printed photo. In the end, we arrived at settings which could be applied globally to reflective scanning, with a slight variation for transparency. These settings are being documented and will be consistently applied going forward. I will point out that the improvement with transparencies in particular, has been significant with the new settings.

Initially, I was reluctant to make changes to any settings. I was suspicious that changes to settings might alter the image, not make it more faithful to the original, as these changes definitely have. Perhaps that reflects my inexperience as much as anything, but I think that this is where the two perspectives I alluded to converge. When I think again about why we’re producing and preserving these images, I welcome any process that refreshes the dialogue and re-centers my work; that brings curatorial thinking to bear again and again on a process (like scanning images) that can easily become mechanical.

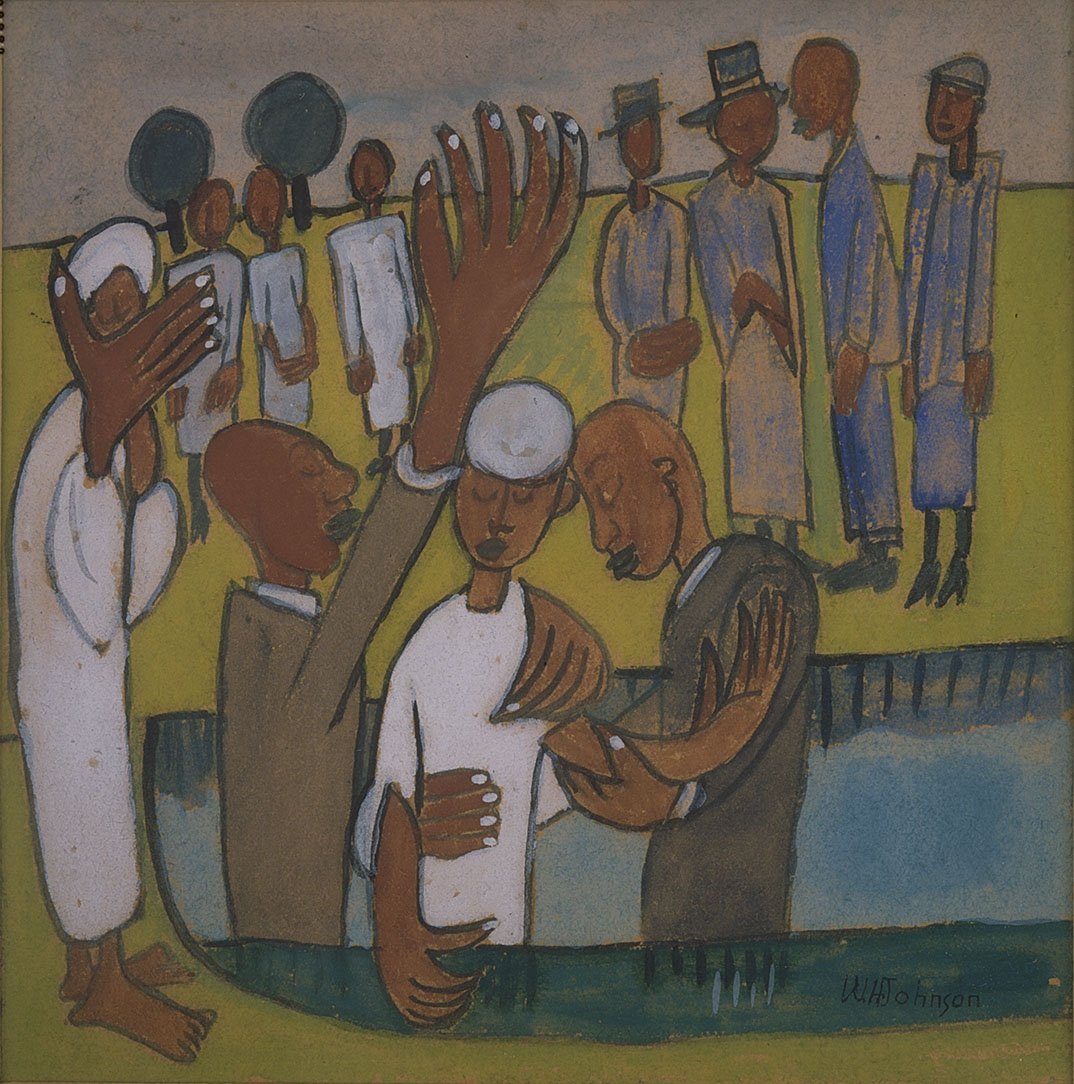

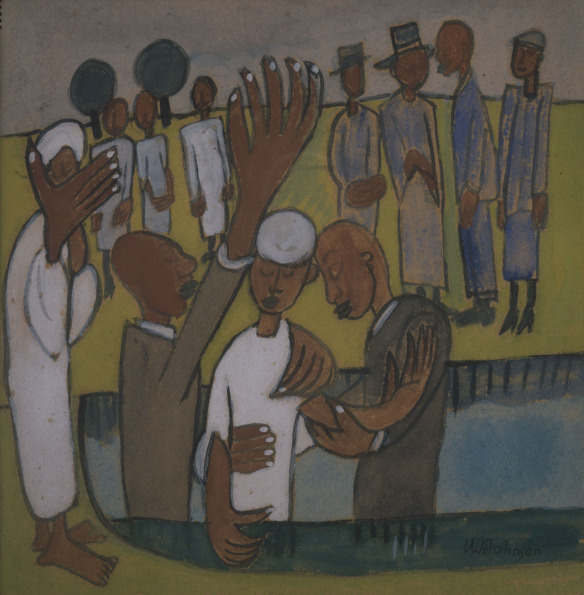

before & after (transparency scanning):

William H. Johnson

I Baptize Thee (study), n.d.

L1998.01.038

From the Collection of David C. Driskell, the David C. Driskell Center

Photography by Greg Staley

This post was written by David Conway.

[ad_2]

Source link