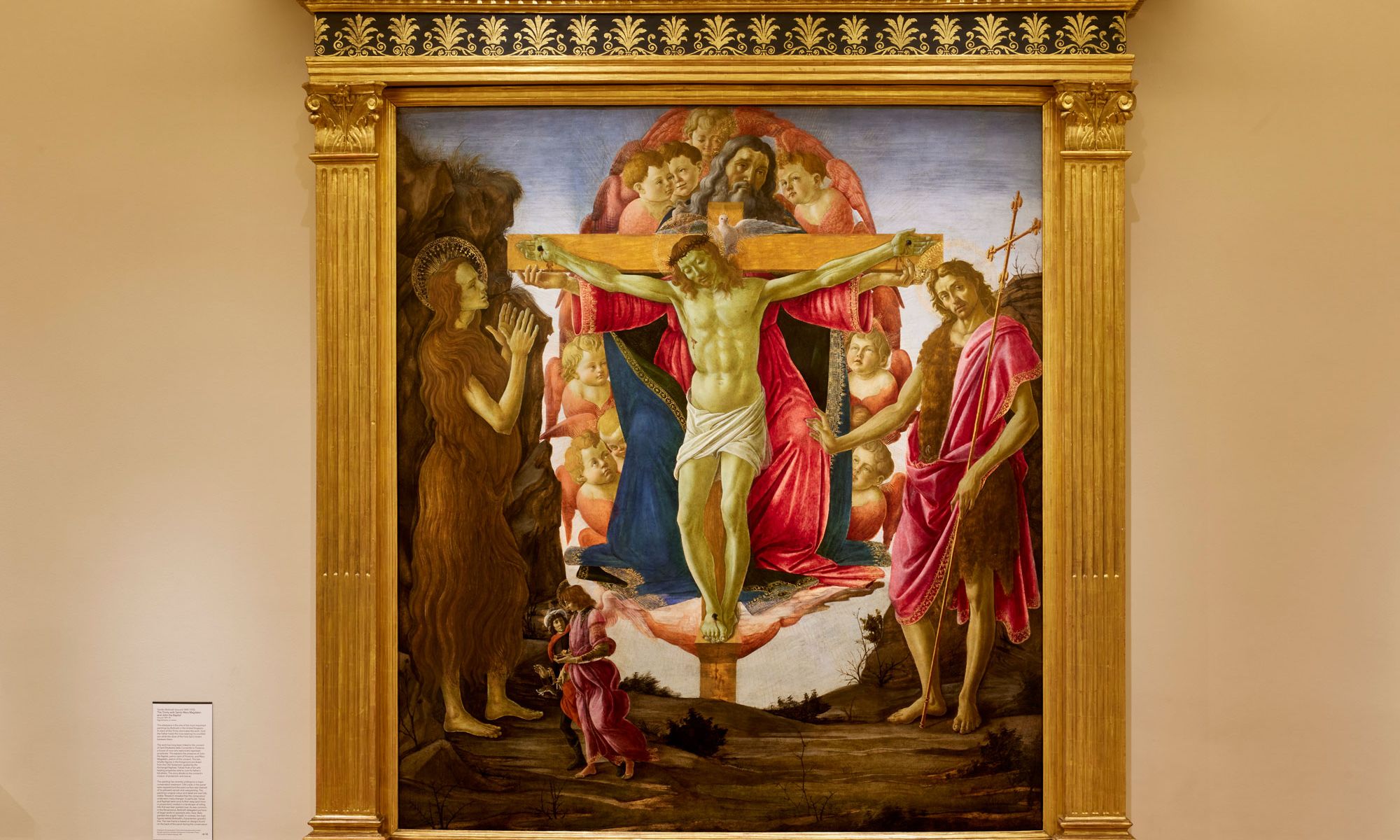

Sando Botticelli's restored altarpiece The Trinity with Saints Mary Magdalene and John the Baptist (around 1491-94) at the newly refurbished Courtauld Gallery © The Courtauld. Photo © David Levene

Among the highlights of London's refurbished Courtauld Gallery, which reopened on 19 November, is its newly restored Botticelli, The Trinity with Saints Mary Magdalene and John the Baptist. This 1491-94 altarpiece, one of the most significant works by the Renaissance master in the UK, had been in restoration since January 2018.

Despite its art-historical importance, beauty and scale, the altarpiece had received scant attention from the British public, due in part to its condition. An imposing work, with a fascinating history and iconography, its luminous egg tempera colours lay buried under darkened yellow varnish and its composition was disfigured by cracks in the poplar panel support.

Now, following treatment led by the Courtauld’s chief conservator Graeme Barraclough, the painting can be viewed afresh, and is presented in a specially designed tabernacle frame. Moreover, the technical studies undertaken during the restoration process have cast valuable light on both the workings of Botticelli’s studio in Florence during the 1470s, 1480s and 1490s, and on the question of attribution.

Botticelli’s The Trinity with Saints Mary Magdalene and John the Baptist, pictured before its conservation treatment Photo: courtesy of the Courtauld Gallery

The painting has long been associated with the convent of Sant’Elisabetta delle Convertite in Florence, which welcomed repentant prostitutes. This explains the focus on Mary Magdalene, the patron saint of the convent, and John the Baptist, the patron saint of the city. The Holy Trinity hovering at the centre of the composition is presented as the vision of the penitent Magdalene.

The iconographical importance of the two saints, whose hairy garments refer to their long periods in the wilderness, explains why they would have been the focus of Botticelli’s own contribution. The infrared discovery of subtle adjustments support this—for example, changes to the hand and eye positions of the Magdalene figure, which bears a close resemblance to Donatello’s unsparing and moving 1453-55 wooden sculpture of the saint. During restoration, a similar belt of hair, with light delicately catching it from below, has emerged from the hair that clothes her.

Nevertheless, as Scott Nethersole, an Italian Renaissance specialist at the Courtauld, explains: “It is still very difficult to understand the many stylistic inconsistencies between the figures of the Magdalene and St John.” He has concluded that the altarpiece must have started life in the 1470s, with some figures repainted and other passages initiated as late as the 1480s and 90s. The studio clearly played a key role in the picture’s execution, supplying, for example the array of relatively poorly painted angel heads. The whole is quite thinly and rapidly painted, though some of the rich glazes are missing.

The most surprising aspect of the composition is the inclusion of the tiny duo of Tobias and the Angel in the foreground, partly due to their sheer disparity of size. They also represent one of the most surprising aspects of the restoration. Originally, these two figures were entirely in scale, occupying a distant landscape that filled the lower right foreground, rolling up to the edge of the Trinity grouping—and which is now painted over with sky. “We always knew that Tobias and the Angel had been moved,” Nethersole says. “We knew there was under-drawing, but we never knew they had been fully painted in their original position.” Those painted figures, he suggests, were made by Botticelli’s assistant, Filippino Lippi.

Conservators discovered that the figures of Tobias and the Archangel Raphael were originally painted in a different position, seen here in infrared Photo: Tager Stonor Richardson

The revised figures—placed in a foreground position usually reserved for donor portraits—have been flipped, to give more emphasis to the protective figure of the Archangel Raphael. They are incredibly finely done, probably painted by Botticelli himself late in the painting’s gestation, and must have been of considerable significance to whoever commissioned the panel.

Other revelations come from a major structural treatment funded by the Bank of America Art Conservation Project, which focused on the reversal of a 19th-century attempt to reinforce the warped and split panel with the addition of batons to the back. The team always knew there were contemporary sketches on the back, but these had been partly obscured. Now they may be interpreted as sketched designs for a tabernacle frame, which would suggest that the architectural structure was designed at the same time as the panel was prepared. There is also a small sketched crucifix.

A detail of the back of the Botticelli altarpiece, showing contemporary drawings of a pilaster and capital Photo: courtesy of the Courtauld Gallery

Removing the later frame has also revealed foliage at the panel’s bottom edge, recovering the foreground and a sense of spatial recession. Adjustments to the way the elements sit in front of or behind the landscape have, however, made it an impossible space. For instance, the left upper arm of the cross has been moved in front of the rocky spur. Nethersole speculates that this landscape is deliberately “irrational” to emphasise the subject’s visionary aspect.

As for attribution, the picture is now displayed at the Courtauld as Botticelli and workshop. “I think it is a category of work that would have been acquired as a Botticelli in the 15th century, but it is not a full Botticelli in the 21st-century sense,” Nethersole says. It forms the glorious centrepiece of the restored second-floor galleries, the Blavatnik Fine Rooms, and will also be the subject of a special exhibition in 2023, where the full restoration findings will be published.