Reporter, HuffPost

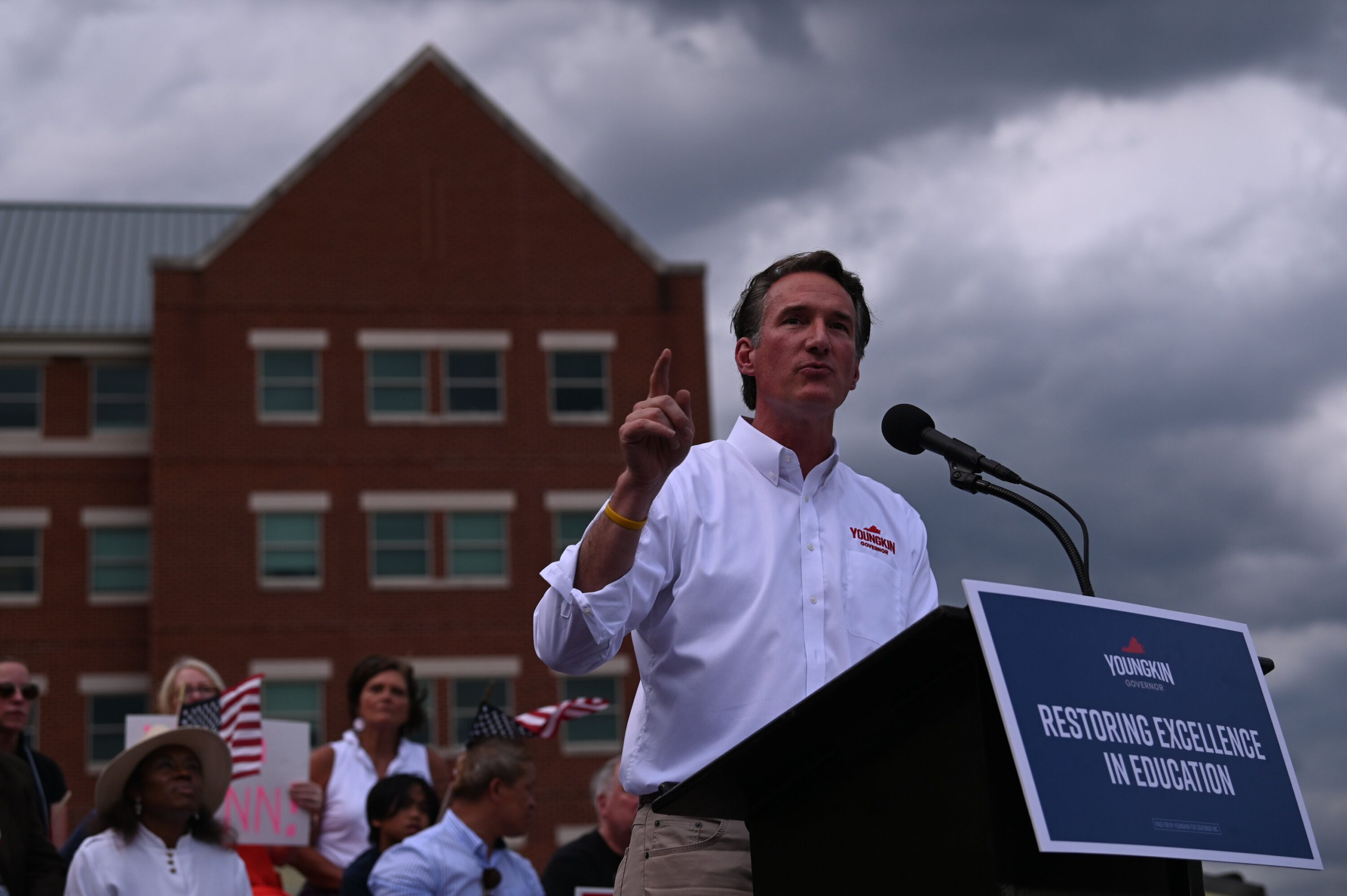

The Virginia gubernatorial election won by Republican Glenn Youngkin, the former CEO of the private equity firm The Carlyle Group, confirms that Donald Trump’s presidency inaugurated a new era of high-turnout elections.

He did so with a kind of racially coded appeal that Republicans have used to forge their winning coalition over the past 50 years but have updated for the Trump era. The issue of the teaching of “critical race theory” ― a post-civil rights era legal theory that racism is systemic in American law and institutions ― in public schools provided an ambiguous enough target to mobilize the rural Trump base to go to the polls while overlapping the issue with other education-related anxieties for persuadable suburban voters.

In Virginia, the critical race theory issue did not focus on the teaching of actual critical race theory, which is almost exclusively taught in universities and law schools. Nor did it solely focus on clumsy anti-racist teachings or the ideas that some anti-racist consultants promote that stem from critical race theory concepts.

But the issue still helped Youngkin turn out the base without scaring off swing voters in the way needed to win amid high turnout.

Finding an issue to do both was needed to win amid high turnout. Every election since Trump took office has seen increased turnout from a more motivated electorate. The 2017, the Virginia gubernatorial race saw turnout hit a record that was broken again this year. The 2018 midterms also saw record-high turnout, as did the 2020 presidential race. Each election appears to be building on the one that preceded it — and any lingering doubts that Trump’s effective absence from the political scene would dampen turnout have been quieted.

Though high turnout was once thought to confer an advantage to Democrats, with their base of support among lower-propensity voters, Trump’s mobilization of the electorate, on both sides, means that Republicans remain as competitive in a world of high turnout as they were when voter numbers dropped precipitously, as they has in elections prior to Trump’s election.

Youngkin’s win and the unexpectedly close New Jersey gubernatorial election, which had much lower turnout, also show that the GOP can do it without Trump on the ballot.

The main effect of Trump’s two presidential election campaigns has been radical polarization along lines of educational attainment. Not only did he reveal and turn out a whole new batch of non-college-educated white voters who lean to the right, but he also converted some non-college-educated Latino voters (and non-college-educated Black voters, to a much lesser extent) to vote Republican. At the same time, college-educated voters of all races went Democratic at the presidential level at higher rates than ever before.

Youngkin’s win is a warning to Democrats that Republicans have a strategy for maintaining sky-high support from non-college-educated white voters, especially in rural areas, that doesn’t deter them from persuading some suburban voters who had swung hard to Democrats. This augurs very poorly for Democrats in next year’s midterm elections unless the party finds a way to turn President Joe Biden’s low poll numbers around and mobilize their base.

Virginia’s turnout on Tuesday hit nearly 74% of the record 2020 turnout, which was the highest proportion of a previous presidential vote’s turnout seen in an off-year election in the state. It was nearly 10 percentage points higher than the 2017 gubernatorial turnout relative to the 2016 presidential election vote.

Youngkin won an unprecedented portion of his party’s presidential vote by netting 85% of Trump’s total in 2020. Democrat Terry McAuliffe won just 66% of Biden’s 2020 total votes. Youngkin’s gains came across the board in nearly every county.

Though much focus is on the swing to the GOP in the suburbs that Democrats have come to count on for their wins, Youngkin also hit higher margins than Trump did in heavily GOP rural areas.

The question this raises is whether Youngkin’s incredible vote total can be attributed to getting Republicans out to vote or to persuasion of swing voters. And there are points for both. Youngkin beat Trump’s vote totals in the hardcore Trump-voting rural counties, a huge accomplishment. He also flipped swing counties and cut into margins in the suburbs of Washington, Richmond and Virginia Beach.

Youngkin fought the election largely on the issue of public education. He targeted the suburbs and swing counties by stating his opposition to COVID-19 school closures and mask mandates, a huge point of contention in a state that saw one of the most extended pandemic school closures in the country, and he called for increasing teacher pay. For the rural base, Youngkin, with the aid of the conservative media ecosystem, provided opposition to the teaching of critical race theory that has become a stand-in for all issues related to race, diversity and inclusion in Virginia public schools.

There is an ongoing disagreement over whether Youngking’s win was tied to his campaign against critical race theory or the COVID school closures, or that it was merely the traditional political swing after a presidential election ― the so-called “thermostatic public opinion” in which the opposition party beats the president’s party in off-year and midterm votes, especially when the incumbent is as unpopular as Biden is today. But they can also all be true at the same time.

Just look at the most defining moment of the race, which took place at the Sept. 29 televised debate, when Youngkin attacked McAuliffe for vetoing a bill in his first stint as governor that would have required schools to inform parents about “sexually explicit” books in their libraries.

“What we’ve seen over the course of this last 20 months is our school systems refusing to engage with parents,” Youngkin said. “In fact, in Fairfax County this past week, we watched parents so upset because there was such sexually explicit material in the library they had never seen, it was shocking.”

“You believe school systems should tell children what to do. I believe parents should be in charge of their kids’ education,” Youngkin added.

“Yeah, I stopped the bill, that I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach,” McAuliffe replied. The latter part of that quote was a staple of Youngkin attack ads for weeks.

Youngkin’s attack on McAuliffe conflated the “20 months” of coronavirus school closures with the manufactured controversy over diversity and inclusion ― a school library contained books with passages depicting gay sex. In doing so, he turned McAuliffe’s defense of public school teachers and the LGBTQ community into a dismissive remark about parents being angry that Virginia kept schools closed longer than almost every other state in the country.

In this way, Youngkin’s turning of critical race theory into a framework for a broad-based critique served the purpose it was meant for when it was constructed in a conservative think-tank lab.

Chris Rufo, a fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute, began the campaign to attack critical race theory by highlighting materials used in corporate and government-issued “diversity, equity and inclusion” manuals and trainings. It’s not as though there was no controversy over these issues (or others, like transgender inclusion) prior to Rufo’s intervention, but he explicitly concatenated them into a political strategy. He created a political category label that could become a “master-signifier,” as the writer John Ganz called it, to encompass all anxiety about social efforts, no matter the content, directed toward diversity and inclusion, particularly around race but also around gender and sexuality.

“We have successfully frozen their brand ― ‘critical race theory’ ― into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions,” Rufo wrote in March. “We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category. The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’”

Critical race theory acted as Rufo wanted it to, and it became a master-signifier for all gripes about social change at schools.

Critical race theory came to encompass school libraries with LGBTQ books on the shelf, a phony transgender panic related to a sexual assault in a girl’s bathroom at a school, a mother wanting to ban Toni Morrison’s “Beloved”, lessons that said Andrew Jackson and the U.S. government committed ethnic cleansing and genocide and the elimination of some advanced placement math classes.

Opposition to critical race theory became a mainstay on Fox News. Republicans in the Senate used their time in committees to persistently hammer on the fake transgender sexual assault story, which got picked up on Fox and throughout the conservative media ecosystem. Youngkin closed his campaign with rallies where he promised to “ban critical race theory on Day One,” and an ad featuring the mother who wanted to ban “Beloved,” a book about slavery in America and an escaped mother’s decision to kill her daughter rather than allow her to becoming enslaved.

The critical race theory issue was red meat for Trump’s Republican base while serving as seasoning for suburban swing voters that they could adjust to their own taste.

Even though political swings against the current president’s party are normal in off-year and midterm elections, opposition party voters still need to be motivated and mobilized to turn out, even when the president’s approval rating is as low as Biden’s current 43%, the lowest of any president at this point in their term, aside from Trump. The critical race theory issue nationalized the election for base voters and kept them engaged and angry, whether they lived in the Loudoun County suburb where critical race theory activism was at its highest or in the rural areas where Republicans needed to stay highly motivated to compete.

And, just as crucially, it didn’t scare off swing voters the way Trump’s more vulgar racist appeals did. They could construct their own version of critical race theory to combine with preexisting anxieties about pandemic school closures. It enabled critiques of whether schools were prioritizing education or a confusing social theory, as can be seen around the elimination of some advanced placement classes. There are also critiques of some of the concepts that have become emblematic of what Rufo describes as critical race theory from liberal writers.

The critical race theory issue can then be seen as a Trump-era update to the coded racial appeals that powered the conservative movement to political dominance over the last 40-plus years.

In 1992, Tom and Mary Edsall wrote in their book “Chain Reaction” that GOP dominance emerged from the interplay of the race and taxation issues. Working-class white voters, once the bedrock of the Democratic Party, began to defect to the Republicans in this period as the GOP successfully linked anti-tax sentiment to opposition to government programs promoting racial diversity and inclusion, along with the bureaucrats and academics promoting such programs.

“At the core of Republican-populist strategy was a commitment to resist the forcing of racial, cultural and social liberalism on recalcitrant white, working and middle-class constituencies,” the Edsalls wrote.

This strategy started to change under Trump as his personal vulgarity and uncoded racism quickened a political realignment toward Democrats in the suburbs that was already under way. But Trump’s rhetoric also mobilized other segments of the electorate ― rural, non-college-educated whites and some non-college-educated Latinos ― to remain highly competitive. Keeping them motivated without turning off persuadable swing voters is essential to compete in this new day of high-turnout elections.

At least for the moment, critical race theory seems to have served its purpose in Virginia as an issue with a racial appeal just open enough to mobilize the base that Trump built since he entered politics and just coded enough for the suburban middle class that it could blend with complaints about how schools and state government handled COVID-19.

By threading the needle in this manner, the issue also forces Democrats to respond in the worst possible political ways: Claiming the issue doesn’t exist because actual critical race theory isn’t being taught in schools. Blaming whole racial and gender groups for their loss. And, as McAuliffe did in the debate, simply defending unelected state employees and government bureaucrats from voter outrage.

Democrats will need to find their own narrative to mobilize their base at increasingly high levels to remain competitive amid high turnouts. The invocation of Trump and the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol will only work in so many races. Perhaps enacting the policies they ran on will help, too. But what voters really need is a story that mobilizes them. Trump provided that to both sides. And critical race theory may continue to work for the GOP in other races.

Democrats will need to develop a different response and narrative rather than accept off-year and midterm election losses as simply a matter of scientific fact while ceding the field to the Republican Party.

Reporter, HuffPost