[ad_1]

Safe and affordable housing is a basic human need and one that is vital during a public health crisis that cannot be brought under control if people do not have the ability to self-isolate when necessary. And yet for a huge swath of the American population, it is increasingly out of their grasp.

There is not a single state, county or metropolitan area in the U.S. where a minimum-wage worker can afford a modest two-bedroom rental without spending more than 30% of their income. And full-time minimum-wage workers cannot afford to rent a modest one-bedroom home in 95% of U.S. counties.

These bleak figures come from the “Out of Reach” report published Tuesday by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), which every year for the past three decades has revealed the increasingly stark mismatch between what people earn and the cost of a decent rental.

“What the report shows us is just how steep of an affordable challenge low-income renters had even before the coronavirus,” Diane Yentel, CEO of NLIHC, told HuffPost. “And it highlights the tremendous challenges that these same low-income renters face now during the coronavirus and its financial fallout.”

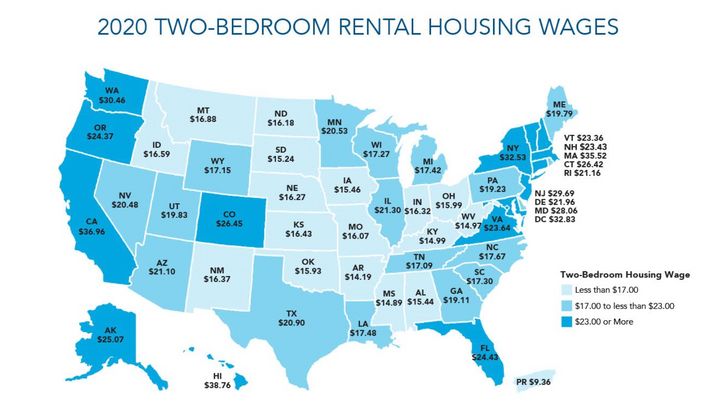

The report calculates a “housing wage,” which is the minimum a full-time worker must earn in order to afford to rent a modest one- or two-bedroom home without spending more than 30% of their income. Above that percentage, they are considered cost-burdened and therefore vulnerable to unexpected financial pressures. This vulnerability is exacerbated for the almost 8 million renters in America who spend more than 50% of their income on housing costs. Considered severely cost-burdened, they are forced to choose between housing and other basic needs, such as food, transportation and child care.

“When you have such limited income to begin with,” said Yentel, “and pay so much of it for your home, you’re always one emergency away from missing rent and facing potentially eviction and, in worst cases, homelessness. So for many of these renters, the coronavirus is that emergency.”

To afford a modest two-bedroom rental, according to the report, a full-time worker needs to earn $23.96 an hour, which is $16.71 above the federal minimum wage of $7.25. For a modest one-bedroom rental, a full-time worker must earn $19.56, or $12.31 above the federal minimum wage.

Some states have higher minimum wages, but even taking these into account, the average minimum wage worker would need to work nearly 97 hours a week (equivalent to more than two full-time jobs) to afford a two-bedroom rental, and 79 hours a week to affordably rent a one-bedroom.

It’s not just minimum-wage workers who are affected. The average renter earns $18.22 an hour, according to the report, which is less than what’s needed to afford a modest one- or two-bedroom home.

Particularly stark in the context of a pandemic is the fact that many essential workers don’t make nearly that much. Grocery store cashiers, for example, earn a median wage of $11.61 an hour, while home health and personal care aides earn $12.94, according to the report. Respectively, they would have to work 83 hours and 74 hours per week to afford a basic two-bedroom apartment.

“We know who the essential workers are,” said Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) on a press call to discuss the report. “We know the anxiety they face at work, where they could get infected, and then we know the anxiety they face at home, when they’re with their families knowing they could spread the disease. Much of this is about housing. Much of this starts with housing.”

There is a huge variation in housing costs per region. The most affordable state is Arkansas, where the fair market rent for a modest two-bedroom is $738 a month, meaning a full-time worker needs to earn $14.19 an hour to afford it without spending more than 30% of their income. At the other end of the scale, in Hawaii, the fair market rent for a two-bedroom rental is $2,015, meaning a renter needs to earn $38.76 an hour.

In neither state is the rent affordable for a minimum-wage worker.

As with every crisis, people of color are hit the hardest. Historic and continuing racist practices, such as redlining, segregation and discrimination, mean affordable homes are even more out of reach for renters of color. While 26% of white renters spend more than 30% of their incomes on housing, that figure rises to 42% for Latinx households and 44% for Black households, according to the report.

“The pandemic is magnifying the racial and gender disparities that already existed in our country’s housing market,” Linda Morris, a Skadden Fellow in the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), told HuffPost.

Not only are people of color disproportionately affected by the virus, but they are also disproportionately employed in the sectors, such as retail and hospitality, hit hardest by the economic fallout of the coronavirus.

An Eviction Tsunami

The housing wage calculated by the report predates the economic crisis that started this spring. “The situation facing many low-wage workers is considerably worse today,” said Dan Threet, a research analyst at the NLIHC.

Even before the pandemic, more than 20 million families struggled with rent. The addition of COVID-19 has had a devastating effect. Almost one-third of U.S. households did not pay their July rent on time, according to a report from Apartment List, with young and low-income households and renters in dense urban areas making up the majority of those who missed payments.

Without a significant federal intervention, there will be a wave of evictions and a spike in homelessness throughout the country.

Diane Yentel, CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition

Around 20% of America’s 110 million renters face eviction by the end of September, according to the COVID-19 Eviction Defense Fund, a Colorado-based legal group fighting eviction and homelessness, with Latinx and African American renters the most affected.

Government assistance has been put into place to offer some protection for renters, but it is limited in both scope and duration. In March, lawmakers increased unemployment benefits by $600 a week as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, but the extra money is set to end July 31, and there is not yet an agreement to extend it. A $1,200 stimulus check sent to most U.S. taxpayers helped, but it was a one-time payment, and it didn’t reach everyone.

Meanwhile, the patchwork of federal and state eviction moratoriums strung together in response to COVID-19, which only ever covered some renters, is now starting to lift.

“Once those protections expire, millions of renters are going to be at immediate risk of eviction and losing their homes at a time when the pandemic is actually worsening,” said Morris.

States that have lifted their moratoriums have seen a surge in eviction cases. In Milwaukee, for example, eviction cases increased by 13%, two-thirds of which were in majority Black neighborhoods.

“It’s really disheartening to see pictures and images of tenants lined up at housing court right now when we’re in the middle of a pandemic and people are supposed to be social distancing,” Morris said. “The impact of the pandemic right now is going to have lasting consequences, consequences that we will see for decades to come unless our government takes action.”

The ACLU is calling for an extension of eviction moratoriums and for courts to provide increased protections for renters, including preventing landlords from filing eviction cases unless they can prove the filing is not in violation of any moratorium.

“It’s very clear that without a significant federal intervention, there will be a wave of evictions and a spike in homelessness throughout the country,” Yentel said. “Our work now is to try to prevent this wave from becoming a tsunami. And we’re running out of time.”

The Solutions Are Simple, Even If They’re Not Easy

In the short term, momentum is gathering behind the campaign to cancel rent. In June, Ithaca, New York, became the first city to pass a resolution to give the mayor approval to cancel rent. The proposal, which still needs approval from the New York State Department of Health, would also ban evictions in the city, where 70% of people rent.

If it’s successful, the move will be vital for renters in the city but still a Band-Aid for a desperate situation.

Grassroots organizing is also pushing the issue of affordable housing up the agenda. “We’re seeing rent strikes, we’re seeing low-income renters show up for each other, to try to prevent their evictions from happening,” Yentel said.

But, ultimately, she said, it lies with the government to act both in relation to the pandemic and to attack the underlying causes of the housing crisis.

“We have to work to build something better that lasts beyond this pandemic,” Sen. Brown said. “After generations of housing policy causing segregation and inequality, we have an opportunity to make it part of the solution.”

In May, Brown introduced a bill to provide $100 billion in emergency rental assistance to help people pay their rent and avoid eviction during the pandemic. The bill passed in the House but has had little support from Republicans in the Senate.

NLIHC, which has been campaigning for a national moratorium on evictions for the duration of the pandemic, supports this bill, calling on the government to provide significant federal emergency assistance to protect those experiencing homelessness and provide additional resources for public housing authorities and housing providers.

In the long term, the NLIHC wants to see a significant investment in public housing, increased investment in long-term rental assistance and the ongoing provision of emergency assistance to families experiencing a temporary financial shock, to help them avoid eviction in the first place. It is also calling for the government to ensure housing policies prioritize those with low incomes and the greatest need.

“Allowing homelessness and housing poverty to exist in our country has always been a public policy choice that we make,” Yentel said. “We can instead choose to end it. We have the data, we have the solutions as a country, certainly we have the resources. What we’ve lacked all along is the political will to fund those solutions at the scale necessary, and I do believe that the will for sustained long-term solutions is growing.”

For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to thisnewworld@huffpost.com.

A HuffPost Guide To Coronavirus

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link