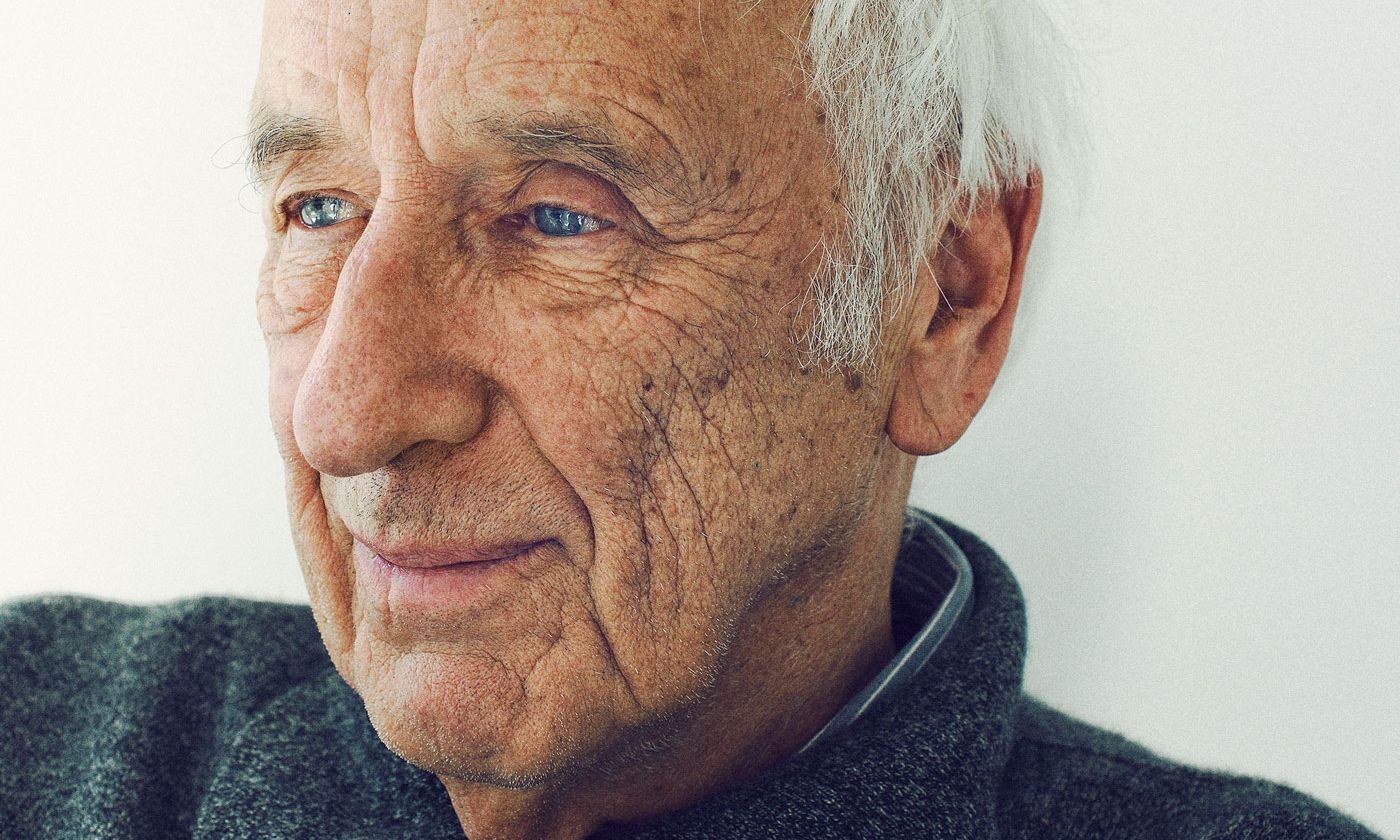

Thomas Hoepker at home. New York, 2012 © Christopher Anderson, courtesy of Magnum Photos.

“I have looked through this little hole for over 50 years to find images in reality,” the German-born photojournalist Thomas Hoepker said, reflecting on his career in the 2022 film, Dear Memories. “Good pictures are rare,” he reflects. “A good photo actually always shows the photographer’s view.”

Following Hoepker’s diagnosis with Alzheimer’s disease in 2017, Dear Memories follows his pursuit of creating one last reportage, travelling with his third wife, the film-maker Christine Kruchen, across North America — repeating a journey made in 1963 — to make the book The Way It Was. Road Trips USA (Steidl, 2022), juxtaposing past and present. Now, two years after the film’s world premiere at Munich Dok.Fest, Hoepker has died at the age of 88.

Hoepker was born in Munch in 1936, beginning his career two decades later while studying archaeology and art history. The recipient of two prestigious national awards for young photographers, he was encouraged to drop university to become a freelance photographer, starting out during the last years of a golden era for photojournalism and the picture press.

The artist Christo with a drawing for his Berlin Reichstag project in his Manhattan studio. New York, 1993 © Thomas Hoepker/Magnum Photos

It was for Kristall that he made that first journey coast-to-coast across the US in 1963, during the last months of racial segregation, shooting a three-month assignment that was turned into a series of photo essays across multiple editions of the magazine, challenging West Germans’ rose-tinted perspective of American consumer culture. And on his return road journey more than a half-century later, travelling during the early days of the Covid pandemic, he found an America similarly divided.

It was Hoepker’s knack for revealing nuanced perspectives on complex social realities through long-form pictorial narratives that marked him out from others, telling stories punctuated by quick-sighted observations that performed as visual metaphors for troubled times. He identified with the humanitarian impulse of “concerned photographers” who sought not just to record the world, but to change it through their images of injustice, and prioritised assignments that gave him the freedom to explore issues over days, weeks or months, rather than chasing headlines.

“He never stopped being curious about the people in front of him,” says Katharina Mouratidi, artistic director of f3—freiraum für fotografie in Berlin, which staged a retrospective of Hoepker’s work last year titled Intimate History. “He was always empathetic, wanting to know about the world, emphasising a humanistic approach. And, besides his excellent technique, that’s what made him an outstanding photographer and human being.”

In 1964 he was given a contract by Stern, Europe’s leading illustrated news magazine, and two years later shot his most iconic images of Muhammad Ali. He travelled the world on assignment over the next decade, while continuing his long-term study of a place closer to home, crossing the border into East Germany as an officially accredited photographer, living there alongside his second wife, Eva Windmöller, a journalist, creating an unrivalled portrait of this now vanished nation.

Downtown Manhattan seen from "lover's lane". Jersey City, New Jersey, 1983 © Thomas Hoepker/Magnum Photos

In between his two epic road journeys across the US, Hoepker spent much of his time living and working in the country, moving to New York in 1976, and becoming the director of the short-lived American edition of Geo two years later. One of his most memorable images, made on his return to full-time photography, captures the Manhattan skyline from the New Jersey shore, framing young couples in “lover’s lane” against the backdrop of the World Trade Center's twin towers in 1983. The landmark buildings would become the subject of his most notorious photograph, shot two decades later.

Hoepker also photographed the city’s elite artists in their studios, starting in the early 1980s and continuing over the coming decades. Among them are memorable images of Andy Warhol as a living screenprint, Jasper Johns reflected in the American flag, and Christo with a drawing for his Berlin Reichstag project.

Hoepker returned to Germany for two years in the late 1980s to become art director at Stern, but returned to New York at the end of the decade and joined Magnum Photos as a full-time member. Besides his obvious gifts as a photographer, his Magnum colleagues remember him as a talented editor.

“He was the visionary driving force behind [American Geo], which was the best magazine I ever worked for,” says Alex Webb, who first met Hoepker in 1979. The two went on to work together at Stern. “There, amongst all the other projects he oversaw, he produced the single best layout of my work that I have ever had in a magazine.”

“Thomas had a smart lens on the world,” says another Magnum colleague, Susan Meiselas, “but his generosity included seeing and celebrating the work of other photographers — whether as an editor at Stern, Geo, or with us at Magnum. His dedication and vision was at the centre of our collective initiative to bring together images from 9/11 [New York September 11, published by PowerHouse, 2001] within weeks of that dramatic event. We raised nearly one million dollars for the families of the victims, which made that book project especially meaningful for us all.”

A picture that overshadowed much of Hoepker's life work: Young people relax during their lunch break along the East River while a huge plume of smoke rises from Lower Manhattan after the attack on the World Trade Center. Brooklyn, New York, 11 September 2001 © Thomas Hoepker/Magnum Photos

One picture missing from the book was one of Hoepker's own. It captures the World Trade Center from the reverse angle of his 1983 picture, this time foregrounded by a small group of Brooklynites, seen in conversation as the smoke consumes Lower Manhattan across the East River. It’s a picture that has overshadowed much of his life’s work, despite the fact that he held it back until five years after 9/11, rightfully judging that it didn’t “feel right” in the immediate aftermath of the attack. For many, including two of the subjects, the picture appears too casual. It is the opposite of the shock and awe we saw in almost every other photograph from New York that day — pictures that made for powerful propaganda for America’s enemies.

“I think the image has touched many people exactly because it remains fuzzy and ambiguous in all its sun-drenched sharpness,” Hoepker wrote in Slate in 2006. “On that day five years ago, sheer horror came to New York, bright and colourful like a Hitchcock movie. And the only cloud in that blue sky was the sinister first smoke signal of a new era.”

Thomas Hoepker; born Munich 10 June 1936; died Santiago, Chile 10 July 2024.