[ad_1]

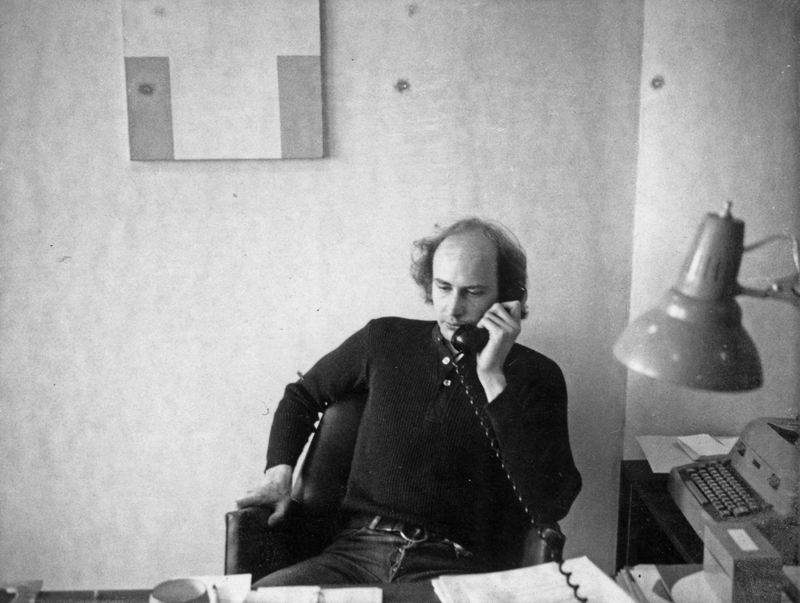

Douglas Crimp at the Guggenheim Museum in 1970.

COURTESY DANCING FOXES PRESS

When art historian Douglas Crimp died earlier this year at age 74, many paying tribute described him as one of the most important critics of our time. Before he would go on to write one of the century’s most important essays, “Pictures,” and to address topics such as art and AIDS, the nature of dance on film, and institutional critique, Crimp got his start at ARTnews, writing reviews of exhibitions around New York. Elizabeth C. Baker, then the publication’s managing editor and later the longtime editor of Art in America, was his mentor. Below, we’ve collected excerpts from his reviews, many of which focus on shows by artists who were, at that point, not widely known. Among the artists he writes about are feminist-art pioneer Hannah Wilke, Minimalist Dorothea Rockburne, and the Kamoingi Workshop, a group of black photographers who sought to define a new aesthetic for their community. The reviews follow below. —Alex Greenberger

“Reviews and Previews”

October 1972

Pat Steir’s new paintings (Paley & Lowe; to Oct. 18) are large canvas surfaces containing a wide range of penciled and painted images: birds, mountains, flowers, geometric figures, color scales; and marks: line, scribbles, letters, words, numbers, strokes, areas, drips. These are executed very freely in some cases, with painstaking realism in others. They are placed sometimes randomly, and sometimes according to a recognizable scheme, located on a grid or symmetrically balanced. Thus she combines methods of chance, even on automatism, with rigorous structural logic.

Steir’s marks and images are employed to examine the nature of signification. She chooses potent subjects—earth, air, water—which she analyses in terms of various formulations: a primarily green “landscape” painting includes green paint, the word “green,” hue and value scales of green; a “water” painting includes the word “water,” strokes and lines which conventionally represent water, characteristics of water like dripping and flowing. These paintings investigate what they are, as opposed to simply being what they are; they provide a lexicon of themselves and, by extension, of painting itself. The resolute disjunction of the bare canvas surface and everything that is done on that surface establishes the fundamental distinction between the language of painting and the neutral carrier of that language. In this way the paintings resist being read either as illusion, which requires spatial coherence, or as object, which requires the identification of the support with its subject.

These paintings have a firm footing in Minimal art; at the same time, they continue a reexamination of Surrealism and its tradition, which was fundamental to Steir’s earlier figurative and symbolic work. Steir’s visit to Agnes Martin in New Mexico in June, 1971, was clearly decisive; Martin’s grid paintings obviously play a major part in the development of this recent body of work.

Hannah Wilke’s wall pieces (Ronald Feldman Fine Arts; to Oct. 13) of rubber latex forms dyed pink/orange, snapped together and pinned to the wall provoke an irrepressible desire to touch them; touching them confirms their sensual appearance, achieved through luscious colors, all on the hot sexual side of the spectrum; and the latex feels organic, if not actually fleshy. Their vulnerability is underscored by their snapped-together structure: it can obviously be undone. The unsettling idea occurs that if you pulled the pieces apart, you’d never get them back together again. Yet beyond wanting to touch, one wants to unsnap—to violate. This metaphor of sensuality mixed with vulnerability is frank and touching.

Of a different character is a wall piece of natural latex units reinforced with parallel lengths of twine. Each of the 14 units has a built-in strength. One has a sense of multiple possibilities of arrangement and extension, and thus a sense of fecundity.

Wilke also shows drawings whose only relationships to the sculptures are pictorial concerns and feminist metaphor. Each of them employs a single collaged piece of memorabilia: greeting cards, advertisements, postcards from the early part of this century. I suspect that their little-girl/little-old-lady insipidity is meant sarcastically, as are their “insipid” pastel stripes. Wilke acknowledges her taste for the “feminine” with a vengeance, harnessing that taste to make tough ambiguous drawings.

“Reviews and Previews”

December 1972

The three concurrent exhibitions this fall at the Studio Museum in Harlem included selections of the work of Henry O. Tanner, photographs from the Kamoingi Workshop and the George Jackson Series of prints of London-based West Indian artist, Llwellyn Xavier.

Culled from the Friedrich Douglas Institute in Washington, D.C., the 35 paintings and drawings by Tanner, dating from the 1880s to the 1930s, record the career of America’s most notable black artist of that period. The exhibition also includes the well-known portrait Eakins made of Tanner, a tribute paid by teacher to pupil, who sat for his portrait on one of his few returns from Paris to this country; Tanner lived abroad so that his race would not inhibit his artistic career.

Tanner’s stylistic range is seen in the juxtaposition of a chalk Study for Portrait of Mrs. Atherton Curtis, a distinctly Eakinsian realist drawing, and an oil portrait of Mr. and Mrs Curtis, a dark washy painting of expressionist turn which almost seems to anticipate Kokoschka. Other paintings of Moroccan or religious subjects have richly glazed surfaces, somewhat like Ryder, although not so darkly romantic. Tanner worked and exhibited in Europe during modernism’s heroic period but never fully embraced the avant-garde; rather, he remained close to his American training and early religious inspiration (his father was a minister). The paintings he made in Tangier hark back to Delacroix, via American romantic realism, rather than looking forward toward Matisse.

The work of 12 photographers was represented at the Studio Museum workshop exhibition. “Kamoingi” means “a group of people acting together” in the language of the Kikuyu people of Kenya. The workshop was established in 1963 “to alleviate the atmosphere of isolation under which black photographers operated in America in the 1960s” and “to serve as a photographic mirror of the black community.” Although a number of these photographers have moved by now to more universal or abstract subjects, those who keep a documentary quality seem to me the most moving and successful. For example, the interiors and portraits by James Francis, like Walker Evans’ work of the ’30s, record harsh poverty so honestly and simply as to be both beautiful and heartbreaking. The power of many of the photographs in this show is achieved by the relation of the image to the way it is framed: Albert Fenner’s architectural subjects, absolutely dead center, symmetrical, isolated; or the squeezed, caged feeling engendered by Herb Robinson’s pictures of black children. Adgar Cowans exploits more experimental pictorial devices—in a photograph of three people on a street taken from directly above, what is seen is not the people but their shadows standing vertically in the frame.

The George Jackson Series of prints by Llewllyn Xavier is a combination of images and words derived from Xavier’s correspondence with Jackson—photographs, passages like those in Soledad Brother—and comments and postal documents from various political activists like Jean Genet, to whom Xavier mailed his work for their contributions. The artist calls his work “contributory art,” a form of art as political action.

“Reviews and Previews”

January 1973

In her one-woman show at the new Nancy Hoffman Gallery (Jan. 6-25), Marjorie Strider is represented by a large body of work from the last two years. The unity behind her disparate ideas stems from her use of brightly colored urethane foam, which appears to ooze out of or around everything. Included are two large-scale sculptures and a number of smaller works. The latter, some in the form of brooms and dustpans, look like those animated cartoons in which everyday objects come to life; the brooms seem to sweep futilely on their own at some amorphous liquid substance. Certain pieces are cast in bronze and painted to look like shiny plastic, thus absurdly contradicting their actual weight.

The most striking works in the show are painting-reliefs of motifs from antique Greek vases, executed in acrylic on gessoed masonite that stimulate the mat surface of pottery. The masonite is cut in several pieces and bonded together with urethan foam; the pottery “fragment” appears to have been shattered by the expanding foam. This work has the comic-horror of those lowbrow films from the late ’50s in which monsters threaten to swallow up the entire world in amorphous ooze.

These pieces seem to imply that the tradition of Western art is being consumed by the tawdry, ludicrous plastic of the present, and seem to suggest a perverse pleasure in that idea. The incredible vulgarity of Strider’s work is immediately hilarious, but on reflection it becomes disconcerting. It is difficult to know just how seriously to take Strider because when you arrive at her more serious ideas you still feel you must be joking. For example, in the “Greek vase” pieces, her hybridization of painting and sculpture is so slapstick that one wonders if such an esthetic proposition can seem any less absurd than the tradition which it would overthrow.

“Reviews and Previews”

February 1973

The new work of well-known Californian Larry Bell is current on view at Pace (to Feb. 7). The two examples in the exhibition are further elaborations of the huge, free-standing glass panels joined at right angles that Bell showed last season. The glass slabs, mineral coated by an elaborate industrial process which modulates the surface from reflective to transparent, are placed in a configuration which forms a corridor that acts like a maze as the viewer walks through it. The effect is perceptually confounding when one is inside the corridor; but seen from a distance, the shapes are simple and obvious. Bell has introduced ambiguity and vertiginous reflections by treating his surface to provide spatial illusion; he thereby unequivocally parts company with the Minimalists, who strove against pictorial illusionism with all their might.

An artist more closely aligned with Minimalism than Bell, Fred Sandback recently showed several works at Weber. These were all composed of lengths of colored elastic cord (one color per sculpture), stretched taut between points on the floor, on the wall, or across corners. The gallery was empty except for these lines “drawn” here and there; but ultimately the works encroached on the space, incorporating space into their own strategies. Thus the lines defined by floor meeting wall, or by two walls meeting, became measuring devices for perceiving the placement, relative length, angularity and actual visibility of Sandback’s lines.

“Judd, LeWitt, Rockburne”

March 1973

“Drawing Which Makes Itself” is the title of an exhibition of new works by Dorothea Rockburne, recently at the Bykert Gallery. Four of these works have as their nucleus double sheets of 34-by-40-inch carbon paper, from which lines are traced directly onto the walls and floor of the gallery, both of which were painted white for the occasion. They are drawings whose image represents a conjunction of elements directly related to the carbon sheet itself—its shape size and potential for repetition….

What we gain through our investigation of the work is a sharing of Rockburne’s particular insight into the relationship between conceptual and perceptual aspects of thought process. I was struck, for example, by the difficulty in determining whether lines are parallel or skew, whether a figure is a square, a rectangle or a parallelogram when these figures were only partially drawn, when their sides intersect, or when my angle of vision caused distortion. That is to say, the simplest aspects of plane geometry cannot be isolated or reconstructed mentally directly from the visual evidence, but require a constant interchange between what is seen and what is known.

“Reviews and Previews”

Summer 1973

The drawings of German artist Hanne Darboven (at Castelli downtown) perfectly fulfill the promise of serial art. Darboven invents arithmetic systems which provide a working procedure for pages of pencilled notations; these take the form of charts, lists or drawings of numbers and rows of regular, wavy pseudo-writing. The exhibition included indices to the extended drawings and portions of the drawings themselves.

Darboven’s notational systems are so ambitious that a given drawing might stay in progress for years. The systems are indecipherable because they are personally invented and inherently meaningless; thus, they simply provide the framework which allows her always to know precisely the next step, never to falter. Darboven exhibits an uncommon sense of artist purpose and her work has a clarity, precision and scope unimaginable in a less systematic art.

Work by Joel Shapiro and Richard Tuttle, comprising the first two shows at the Institute for Art and Urban Resources Clocktower, nearly ceded the spectacle of the exhibition to the spectacle of the space itself. The Clocktower is indeed an exhilarating space; it consists of two nearly cubical rooms, one atop the other and connected by a spiral staircase, plus a balcony with a dazzling lower Manhattan view.

In the larger of the two rooms, Shapiro placed a tiny metal bridge on the floor; upstairs a miniature balsa wood ladder leaned against the wall and two life-sized bronze birds sat on a small shelf. Shapiro’s work suggests a retreat from the enormousness of recent American art almost to the point of zero visibility. So fragile that its very existence seems tenuous, Shapiro’s work avoids preciosity even as it approaches the size of jewels. One thinks of the kinds of objects of no economic worth so cherished by children, which are totally invested with their own special meanings. Similarly, it seems that Shapiro’s concern is that the viewer impart his own meaning to these diminutive objects.

Richard Tuttle showed 12 versions of his 1969-1970 white paper octagons, glued flat on walls. Some were affixed well above eye level at Clocktower, and because the white paper was only faintly different in tonality from the whitewashed walls, the works took some time to locate. Once found, their irregular octagonal shapes subtle commanded and concentrated attention. Tuttle achieves an absolute presence by rejecting the muscular impact on expects from New York art.

[ad_2]

Source link