[ad_1]

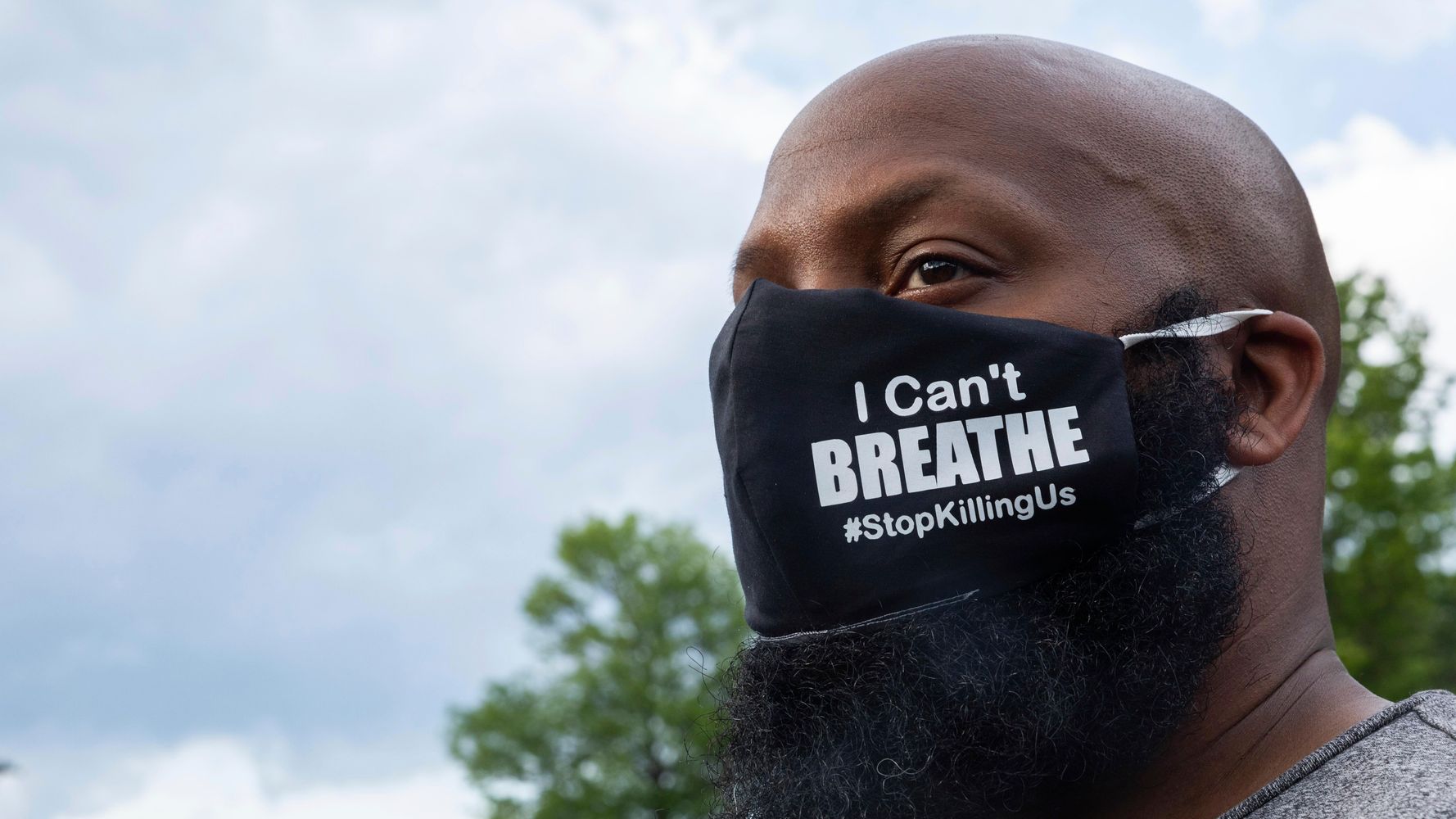

As nationwide protests continue over the death of George Floyd, a Black man who was killed when a white Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck last month, Ohio is trying to declare racism a public health emergency.

Other jurisdictions are exploring similar declarations, but if this measure is successful, Ohio would be the first state in the country to name systemic racism as a public health emergency.

“Ohio must address racism by developing policy to address racial equity to protect all Ohioans, not just certain people,” said State Rep. Juanita Brent (D-Cleveland). “There are racial disparities in healthcare, housing, workforce development, and every fabric of our system. That is why we must continue to stand together, let our voices be heard, and fight just as our ancestors did.”

Ohio’s resolution — identical versions of which will be introduced in the Ohio House and the Senate — calls for commitment to 11 actions, including education to address and dismantle racism; promoting and encouraging all policies that prioritize the health of people of color; and securing the resources needed.

Racism is a pervasive social outrage, one that touches every area of racialized people’s lives, especially Black and Indigenous people. Police brutality, environmental racism, and the psychological toll of racial aggression are all health issues.

“Revolutions are not a one-time event,” Brent added, a sentiment that feels particularly urgent during this current uprising, as Black people risk our health during the coronavirus pandemic, fighting for our lives against a militarized police force that keeps killing us. As Brent said, the fight is far from over.

COVID-19 is disproportionately killing Black people

We cannot ignore the fact that this surge of national outrage comes during a global pandemic; one that has, in the U.S., disproportionately impacted Black communities. According to an analysis of demographic data, Black people are dying at a rate “nearly two times greater than would be expected based on their share of the population. In four states, the rate is three or more times greater.”

This isn’t because we’re inherently more susceptible to this virus, but because of social inequities that have led to more preexisting conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and HIV. Communities of color breathe in the pollution that white communities create, and this environmental racism has also led to much higher rates of cancer and asthma (which is a risk factor for COVID-19 complications) in Black communities.

Other factors contribute to our heightened risk of coronavirus: Black people are more likely to have jobs that force us to expose ourselves to the virus, and we are more likely to use public transportation for our commutes.

Financial circumstances often cause Black families to live in multi-generational households, which can endanger elders or simply provide more opportunities for the virus to transmit. COVID-19 testing was also initially more difficult for Black people to access, because Black neighborhoods are more likely to be “health care deserts” — neighborhoods without doctors or medical clinics.

We can not discuss health, especially in these times, without discussing systemic racism.

At protests against police brutality across the country, police have fired tear gas — which can cause respiratory damage — into crowds, potentially exacerbating future cases of COVID-19, which is a respiratory disease.

We cannot discuss health, especially in these times, without discussing systemic racism.

Racism and other health outcomes

Declaring racism as a public health emergency — all over the country, not just in Ohio — is crucial because we have to understand that these disparities are intentional, and therefore preventable. Race is not a genetic construct, but a social one. So we must find social solutions.

Dr. Lauren Powell, who leads work at TIME’S UP that focuses on reducing sexual harassment and discrimination experienced by providers and patients, said that one way to do this is setting up “health equity task forces that are codified in state legislation and come with financial resources to create programs specifically to dismantle the impacts of racism from multiple levels.”

She also stressed that these policies must be permanent. “The challenge with government declarations is they can fade away with changes in leadership,” she said. “And so my challenge to states who are considering this is, how do you make this permanent?”

Dr. Nia Heard-Garris is a Black pediatrician working in Chicago, who studies racism and its impact on children. She’s a native of Cincinnati who lived through the city’s 2001 protest against the police killing of Black teenager Timothy Turner, and sees Ohio’s step towards declaring racism a public emergency as an encouraging step: “I’m really proud of Ohio and I think other states should do the same. Institutions like schools, universities, companies should also follow suit in dismantling racial inequities.”

But she also said that “without any kind of fiduciary responsibility, I think it’s going to be just talk. If people don’t have incentive to end these racist health disparities, it’s easier to refuse to move towards meaningful change.”

The current version of the Ohio resolution would be non-binding, meaning there would be no sanctions for those who do not follow it.

These changes must address health disparities caused by racism. Heart disease is the leading cause of death for Black women but according to the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, this is largely due to race-related stress, barriers to care, and racism from health care providers. Black women are 69% more likely to die from coronary artery disease than white women, and 352% more likely to die from hypertension than white women. These differences are because of racism. But not everyone is willing to face that.

“When [doctors and officials] see health differences between Black and white people, they often think there’s a genetic underpinning,” said Heard-Garris. “But we’ve said time and time again that structural racism is the reason for most of the disparities that we see; not biology, not genetics.

“Those ideas have had to pervade our society in order to devalue Black life … to serve not only white supremacy, but to also serve the financial and economical aims of the slaveowners, who needed to prove that we were built for labor or less than human.”

In a statement, the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) ― a group of 3,000 local health departments across the U.S. ― expressed support for actions like “eliminating discriminatory policing practices, such as racial profiling and stop-and-frisk, which disproportionately target Black people and communities,” and “holding police accountable for discriminatory actions and discriminatory use of force.”

But most of NACCHO’s proposals are not comprehensive enough. And while Ohio’s proposals are somewhat more specific, we have been “committing” ourselves to these same actions for years. Governments and officials will have to work much harder to solve this issue and present much more detailed plans.

Policing and mass incarceration

Prison and police abolition could also play a role in addressing these health issues. Police alone killed 1,004 people in 2019, and the victims were disproportionately Black. Mass incarceration threatens public health in multiple ways, not least of which is its high mortality rate.

Even witnessing police brutality — on video or up close — can lead to mental health issues. After the deaths of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and many others, Powell said she finds herself crying and mourning. She recognized that for Black protestors on the ground and people watching videos of police brutality, that anguish is also present.

“We have these visceral and visual illustrations of the metaphors that we have said all along in the Black community, like ‘Racism is like a knee on my neck.’ And then we actually see someone die that way,” she said. ”I no longer can watch the videos because they replay in my head and they give me nightmares.”

And for those close to the victims of police brutality, the stress and grief can kill them. Fifty-eight-year-old Marquis Jefferson died from cardiac arrest and heart complications after his daughter Atatiana Jefferson, a 28-year-old Black woman, was shot and killed by a white police officer while she was playing video games with her nephew in October 2019. Erica Garner, 27, died of a heart attack shortly after giving birth in 2017. She had been fighting tirelessly for justice for her father, Eric Garner, who died in 2014 after a white police officer used an illegal chokehold on him. Eric Garner’s stepfather, Ben Carr, also died of a heart attack.

When I think of these stories, real solutions seem further and further away. But then I remind myself that there are real solutions — abolishing prisons and police, increasing the Black and native birth worker force, passing “Medicare for All” and more. We just need leaders with the courage and conviction to act.

Heard-Garris said that “racism has always been a public health issue since the day slaves were brought to this country.” For her, it seems medicine and governments have been slow to realize this because “to acknowledge racism as a public health issue is to acknowledge our [complicity].”

Powell says that “recognizing racism as a public health emergency brings additional resources and a spotlight on the importance of eradicating racism. It also makes it clear that it’s not the job of those who experience racism’s impacts to dismantle racism.”

And during this extraordinary time in history, this revolutionary time, we must be honest about how this country has threatened the health of Black people and other communities of color for centuries. This is not a simple problem, or a new problem. But it is a problem we can solve.

For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to thisnewworld@huffpost.com.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link