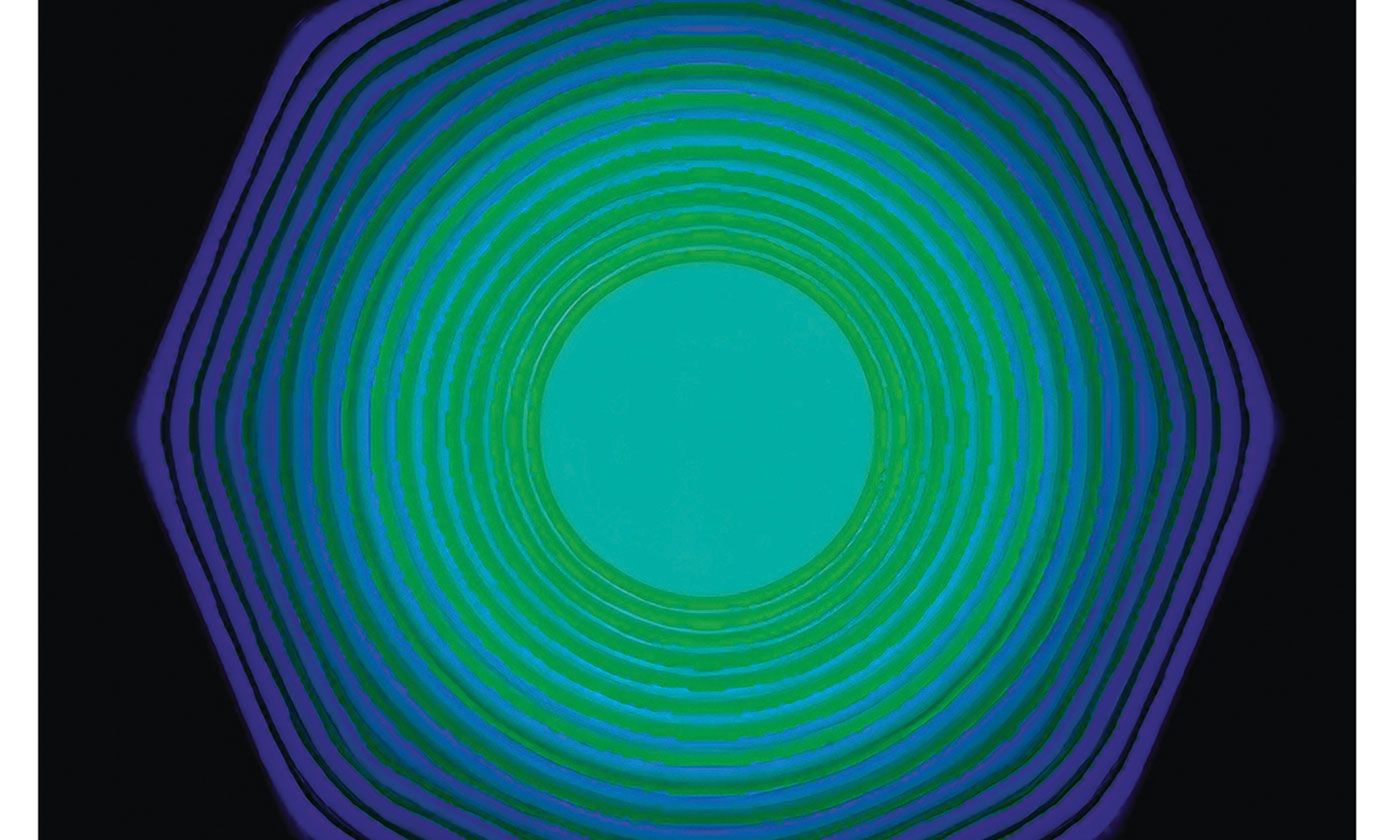

“This idea has refused to die”: Kevin McCoy, Quantum (2014), the first non-fungible token (NFT), a 179-frame screen recorded loop from a code-generated animation. From Robert Alice (editor), On NFTs (Taschen, 2024) Courtesy Kevin McCoy

The 10-year anniversary of a once-controversial new form of digital art, and disruptor of the art market, NFTs (non-fungible tokens), falls on 2 May.

In the lead-up to that anniversary, two important new publications combine to provide the first comprehensive history of a form that the art historian and critic A. V. Marraccini calls “a commodity, a provocation, a para-medium, a shibboleth, an inscribed artefact of capital at speed". On NFTs, edited by the artist and writer Robert Alice and published by Taschen, and a collected volume of essays drawn from the website Right Click Save, come with two complementary kinds of authority.

On NFTs is substantial in size and price—£750 for its cheapest first release (a general trade edition will follow later)—and has the feel and rigour of a catalogue raisonné. Its editorial aspiration, marked by that “On” in the title and each of its component essays, comes rooted in the grand tradition. “The title On NFTs is inspired by the art-historical and cryptographic tradition of the treatise," Alice writes, "exemplified best by the Renaissance artist, art historian, and cryptographer Leon Battista Alberti’s … two treatises De Pictura/On Painting (1450) and De Cifris/On Ciphers (1466). Before the advent of blockchain, there exists no one individual in history who has furthered the dual fields of art and cryptography in equal measure.” Alice tells The Art Newspaper that he sees On NFTs as “a slow look at a fast art”.

Right Click Save is witness to ideas taking flight as NFTs exploded, imploded then rose again. Writing in the introduction, Alex Estorick, editor of both the book and the online magazine, says the book's purpose is to create “a series of new media genealogies — what we termed 'crypto histories' — that situated ongoing developments within an expanded understanding of art.”

Both books are serious and compelling in their attempts to align NFTs with a wider perspective of the art market and art history. But looking back is only half the story. As NFTs begin their second decade it is important that their history is understood. Equally—as both books make clear—here is a compelling story still forming in a rich, complex artistic and cultural ecosystem around NFTs and the wider technologies of the blockchain and Web3 that they emerged from.

Robert Alice, On NFTs (Taschen 2024), showing the opening spread of the "NFTs are" section and the slip cover and stainless steel case for the Hard Code edition of the book, which was offered to the first 10 buyers at the auction sale on Christies 3.0 in March of Alice's related generative art series SOURCE [On NFTs] Courtesy of Taschen and Robert Alice. Photograph © Mark Seelen

Artists are adopting NFTs in their practice and leading museums have recently adopted them as part of their visitor experience. New kinds of cultural and public institution are forming around the blockchain technologies that NFTs are based on. And the sales market itself is in a new phase of growth after the wild explosion and near collapse of 2021 and 2022.

At a time when digital art is capturing public attention in numerous domains, now is a good moment to ask again why NFTs matter, and what they tell us about the future of art in a digitising world.

On 3 May 2014, the artists Jennifer and Kevin McCoy were attending the Seven on Seven conference organised by the the “born-digital” art non-profit Rhizome in New York City.

During a live presentation, they set out what they describe now as their, “vision of how blockchain systems could bring uniqueness to digital artworks and how such a system could create provenance, verification and markets in a natively digital way”.

The artwork they used to demonstrate this process was called Quantum, a 360×360 pixel, 179-frame screen recorded loop from a code-generated animation, minted on 2 May 2014. It would become the first NFT. From this simple beginning, the McCoys tell The Art Newspaper, “over the last 10 years this idea has refused to die and it is now bigger and more pervasive than we could have imagined.”

Three years later the idea of collectible, tradable, digital assets registered on the blockchain began to take off. The Ethereum blockchain offered a more flexible development environment than Bitcoin or other early blockchain platforms, and its launch in 2015 had given birth to the early NFT art movement by 2017.

That movement began with Curio Cards developed by Travis Uhrig, Thomas Hunt, and Rhett Creighton and released in May 2017. Soon followed by Cryptopunks and CryptoKitties, it established a style for early NFT art—simple illustration, sarcastic humour and pop-culture references —that seemed more an outgrowth of the depths of memes and social media culture than anything with a pretence to “art”.

Seemingly self-contained within its own edgy, sarcastic universe, NFTs and NFT culture grew over the next three years, but it was with the Covid pandemic that NFTs exploded into the mainstream and created their own strange detonation of the contemporary art market.

The NFT bubble of 2021-22 showed how digital markets and digital media frenzy are inseparable in the crypto domain. Whilst the $69.3 million that Beeple’s Everydays — The First 5000 Days sold for at Christie’s in March 2021 remains astonishing, it is the aspirations behind its purchase which seem ambitious even three years later.

Beeple’s collection of his work, popular on Instagram but barely known beyond it, was bought by a crypto-fund called Metapurse. For them it was an asset that would help build a financial ecosystem through the launch of their own crypto-coin, B20—a coin which offered fractional ownership of what was now one of the top three most expensive artworks in the world. Around the B20 coin, Metapurse built digital museums and signed licensing deals—at pace they were constructing not just a new world-famous artist, but also a new kind of financial and art market from that artist. There was little comparison for this, and it was happening so fast it was hard for anyone to keep up.

But people were buying. In 2021, NFT trading—conservatively—reached $13 billion. The NFT was everywhere, and in the depths of a Covid pandemic, it still came as no surprise when "NFT" was named as Word of the Year by Collins dictionaries.

But for Metapurse and others, it could not last. The bottom fell out of the market in 2023. In the wider crypto space, many Towers of Babel were falling all at once with the collapse of Sam Bankman-Fried’s FTX just the most notable of series of disasters that were closer to the avant-garde farce of Thomas Pynchon than the ubermensch fantasy of the books by Ayn Rand so beloved by Silicon Valley.

It was hard to turn away from the remarkable ascent, and then dramatic crash of the NFT from 2021 to 2023.

Digital markets have been prone to boom and bust driven by what the economist Robert J. Shiller calls “narrative economics”—online noise driving a hype-and-crash cycle of extreme speed. But whilst the world was watching, elsewhere, quietly and patiently, new organisations and institutions were building connections between NFTs and the wider Web3 and blockchain culture with art galleries and museums; significant artists were both adopting and emerging from the medium, and threads between NFT art and art history were being tied.

Making connections between NFTs and wider contemporary art and art history has been advocated by the website Right Click Save. Founded in 2021 by Jason Bailey, and edited by Estorick, Right Click Save has pursued three ideas: “to encourage healthy debate; to celebrate digital art for the vital cultural contribution it makes; and to blend the rigour of traditional art scholarship with a form of radical inclusivity that rejects elitism on the basis that art can be made and enjoyed by everyone.” The Right Click Save book, published by Vetro, is an elegant testimony to that purpose.

If Right Click Save has been the storyteller, then Diane Drubay, founder of We Are Museums and the WAC Lab has been its most successful connector. WAC Lab, launched at Art Basel in 2021, is an innovation programme and accelerator. Now in its third cohort, it guides museums and cultural institutions through a structured multi-week programme of understanding Web3, NFTs and blockchain. Each participant develops an early stage prototype project with a specialist blockchain start-up.

Their first notable success was with the integration of NFT collectibles into the digital artist Ian Cheng’s show Life After BOB (September 2022) with the Light Art Foundation in Berlin. Forty-four institutions have so far participated. In its second season, the Musée d’Orsay, in Paris, marked, as Drubay says, “another significant milestone”. After participation in the program, says Drubay, “the museum embraced a bold Web3 strategy, introducing digital souvenirs by Keru and collaborating with the artist and musician Agoria to offer a captivating artistic experience. Visitors were invited to participate in a contemplative artistic experience, blowing into their phones to generate live artwork inspired by the museum’s collection, subsequently minted as NFTs.”

The Musée d’Orsay is one of the largest museums to have shown significant and nuanced adoption of NFTs into its visitor offer. Also in Paris, the Centre Pompidou in February 2023 made a major acquisition of NFTs (and recently acquired a piece by Robert Alice, editor of On NFTs).

In New York, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) has also explored different ways NFTs might become part of its visitor experience. In just a few short weeks in October and November 2023, they launched an NFT collectible as part of their staging of Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised project, and then their Postcards project, which allowed you to create and share simple digital postcards through an NFT wallet. At a point when the SEC was clamping down on the commercial trading of crypto-currency, MoMA acted to show the non-financial way NFTs could be traded on values of friendship and sharing.

Even Beeple, the original renegade outlier of the NFT market, has started drawing threads between his work and the wider art world. After opening a 50,000 sq foot studio in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2023, he has begun working in partnerships with the Gibbes Museum in the city and others. Everywhere now, new connections are being made that tie NFTs to the contemporary and to wider culture, recasting them as another part of art’s rich story.

Playing nice between the world of NFTs and the contemporary and institutional art world is all well and good, but it risks overlooking the crypto-world’s radical roots.

Whilst these bridges are being built, elsewhere NFTs and the blockchain have inspired entirely new visions for what artistic practice, galleries and museums might look like in a Web3 world, rewriting institutional rules and behaviours of cultural institutions for a digital world.

Of the different ways to do this, the blockchain and the Decentralised Autonomous Organisation (the DAO) offers the most potential. It presents a system for alternative hyper-democratic forms of digital governance on which new organisations can grow. Ruth Catlow, founder of Furtherfield, brilliantly explored this in her book Radical Friends (2022), which looks at the different ways in which DAOs could lead to inclusivity, equity and eco-social change.

In London’s Hackney Wick, one model of how DAO’s might shape tomorrow’s art institutions is taking shape: ArtSect Gallery. ArtSect offers one glimpse of an alternative future. But perhaps the key decentralised museum project is Arkive, which emerged out of the mainstream West Coast crypto community. Arkive describes itself as “a museum curated by the people", with a mission to build “the most expansive and representative collection of culturally significant art & artifacts”.

What Arkive represents is a serious, well-funded attempt to build a digital-age museum around the principals of the DAO—and then place it in the middle of the contemporary art world. Founded by the tech industry-veteran Tom MacLeod, Arkive has very rapidly built a community of real action and system-changing potential.

Core to what Arkive does is collective acquisition of art and artefacts—building a collection that, whilst still in its early stages, represents a search for objects that reflect, embody, and witness turning points in art or culture driven by technological advances. From Nam June Paik to Lyn Hershman Leeson, to key video from the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, the community-curated acquisitions are building a collection of significance and with a real point of view.

What Arkive is doing is building leverage. As Arkive grows it will lend its collection. A virtual institution with a collection of real value holds some power to influence change, making new rules that others may need to bend to. It is an example that will inspire others and deserves close attention.

Where will this lead us? What will NFTs, Web3 and blockchain look like when they are 20, 30 or 40?

At a point where digital art is becoming hyper-visible through the rise of what, in February 2024, The Art Newspaper called “the immersive institution”, it may be that what we are seeing is the coming into being of an integrated digital art market which has both end-points where new work by major artists can be both seen by—sometimes—millions of people, and bought by collectors.

That possibility has opened doors for artists of a previous generation of digital art for whom the fragmentation of digital art has meant both creative opportunity but also a terrible fragility in the preservation and market-access of their work.

Auriea Harvey is one of this wide body of artists who’ve worked across web and net art. The retrospective of her work now on show at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image brilliantly captures her experiments in 3D printing and other physical, preservable digital technologies. But a body of her work is absent—the net art, websites and games she has made which over the last 25 years have depended on obsolescent technologies—and are now a sad list of increasingly inaccessible links on her website.

This ultimately is why NFTs matter, and why we are at a transitional moment. As the McCoys saw right back with Quantum, NFTs and the permanent record they create are a chance to document, preserve and build a viable market for digital art that the earlier decades of experiment lacked. They are a common technical standard from which a medium can grow—the closest thing we have to canvas for digital art—in the permanent certification they provide to images, video and other digital formats.

Out of that commonality, the rest of the NFT’s and the blockchain’s rich promise may begin to be realised. As Diane Drubay says, “With blockchain, decentralisation, immersive experiences, and AI advancements, we face a seismic shift in content and culture creation as well as in distribution and ownership. More than the technologies and their applications, it is a redefinition of roles, timelines, and spaces.”

The first ten years have been just the start of the NFT journey. There is much more to come.