[ad_1]

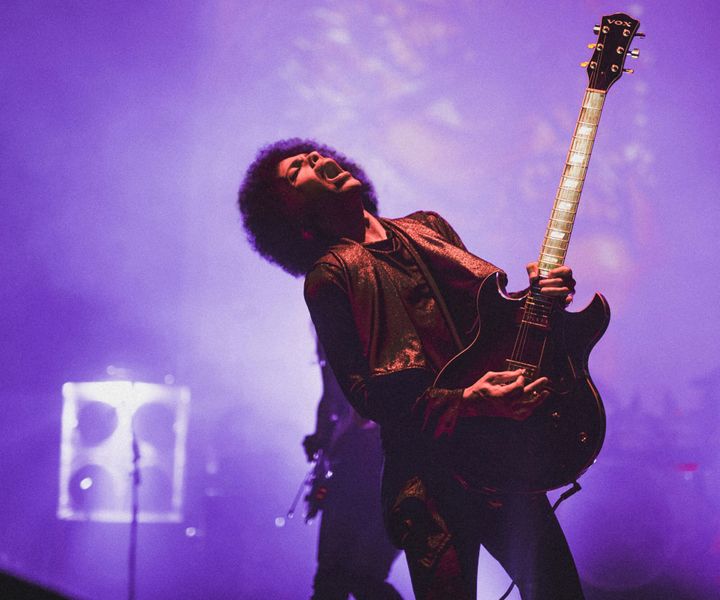

I watched Prince’s performance at the 2007 Super Bowl halftime show from my college dorm room, which was furnished with outdated devices from home. I popped a blank VHS tape into my VCR to capture what music lovers — and internet polls — still consider to be one of the greatest acts in the history of the NFL showcase. For an audience of more than 90 million, Prince sang with passion, shredded on guitar and projected his larger-than-life silhouette on a tarp during “Purple Rain” — in the actual rain. As a superfan who had taken every opportunity to honor his art and influence in my writing and music classes, I was exhilarated.

Years went by and I never stopped writing about him. But for some reason, I tucked my memory of the performance away with the VHS tape. After Prince died in 2016, I heard his hairdresser speak about that night in an interview with The Current, revealing how he’d had a split second of hesitation.

“They’re not going to make me go outside, are they?” he reportedly said. But he gathered himself, put on a scarf and asked the producers, “Can you make it rain harder?”

I shocked myself by weeping over the story. The nervousness he briefly displayed before the show was a reminder that, incredible talent aside, he is not magic — a description he rejected — but human. As a Black female fan with multiple insecurities, I felt pride. I felt seen. I felt like I could still do extraordinary things.

That Super Bowl performance is not in “The Beautiful Ones,” Prince’s posthumous memoir, published by Random House and out Tuesday. But that’s only because he died before completing the book. Still, the book is an affirmation of Prince’s Blackness and humanity. It also provides deeper insight into his relationship with his parents, which he only hinted at in the song “When Doves Cry” and the “Purple Rain” film. In Prince’s own words, the memoir is a “handbook for the brilliant community, wrapped in autobiography, wrapped in biography” — and thus, it’s an inspiration. It successfully captures what made me cry, looking back at Prince playing in his scarf on that wet Super Bowl stage.

Though practical in nature, the scarf has long been a symbol of Black culture — or “soul,” as Prince’s character, Christopher Tracy, said while wearing one in the 1986 film, “Under the Cherry Moon.” It signifies both Black utilitarianism, which dates back to slavery, and Black fashion that is still relevant today. The scarf’s presence, especially on a global platform, is an automatic statement of perseverance and creativity.

“The Beautiful Ones” embodies that same spirit. The memoir is divided into five sections, beginning with an introduction that provides a behind-the-scenes look at its creation. A large part of this section was previously published in The New Yorker, but there are new passages that readers should examine closely; Piepenbring’s conversations with Prince are just as important as the sentences Prince composed himself. And many of them were permeated by race.

As the memoir reveals, white critics’ statements about Prince “transcending” race are incorrect; the superstar was firmly rooted in his heritage. In his own words to Piepenbring, he subverted a racist music industry that sought to trap him on the then-“Black charts” — an offensive label that limited the breadth of Black musicians. Later, he undermined the industry again, fighting for ownership of his music while bringing attention to the oppression that Black artists have faced throughout the years. All Black artists should own their masters, he told Piepenbring.

“He saw it as a way to fight racism,” Piepenbring writes in “The Beautiful Ones.” “Black communities would restore wealth by safeguarding their master recordings. And they could protect that wealth, hiring their own police, founding their own schools, and forming bonds on their own terms.”

The next section of the book includes the 28 pages Prince wrote, bolstered by Piepenbring’s invaluable annotations, and never-before-seen pictures of Prince’s family. Prince writes about his childhood with clarity and poetic flair, effortlessly combining humorous anecdotes with deep self-reflection and musical analysis. His stories express the significant influence of Black women in his life, from the girls he dated to matriarchs in the community. It’s another truth about him that is rarely explored in the media.

But the most important Black woman in his life was his mother, Mattie Della Shaw. His commentary on her — the most he has ever shared — feels like an attempt to correct the narrative about his family. He also addresses the loving and tumultuous relationship between his parents, and how it informed his life and work. He was the true embodiment of his mother and father, of spontaneity and order.

“One of my life’s dilemmas has been looking at this,” said Prince, who also presents a human vulnerability through discussions of his insecurities and epileptic seizures as a child.

The remaining sections of the memoir tell the story of Prince’s ascent to superstardom. There is a photo album from the late ’70s, which was discovered at Paisley Park. He had kept it to document the making of his debut album, “For You.” It also includes handwritten lyrics and excerpts from his interviews throughout the years. It’s apparent that Piepenbring and Random House editor Chris Jackson wanted Prince’s voice to steer the project. It shows the promise of what Ava DuVernay would have done with the Prince documentary for Netflix — which was said to have been “narrated” by Prince — had she not dropped out of the production.

Prince’s memoir closes with his handwritten synopsis for “Purple Rain,” a bit of a dark read that draws on his complex relationship with his parents.

There are some missed opportunities in the book: Piepenbring could have included whatever he and Prince discussed about spirituality, a major aspect of the artist’s life and music, and he could have encouraged Prince to elaborate further on the impact of his father’s strong religious beliefs.

But so much was out of Piepenbring’s hands. We will never hear Prince’s take on milestones like marriage and fatherhood, the “bombshells” he had promised to share, or the lyric-by-lyric breakdown of “When Doves Cry”— a window into his psyche — which he’d expressed interest in doing.

And yet, “The Beautiful Ones” is still a guide, albeit a brief one. It shows that Prince is one of us — he just worked to manifest dreams that took him from the North Side of Minneapolis to the Super Bowl. It encourages us to tap into our power to design the lives we envision for ourselves and set a precedent for future generations to do the same.

“If I want this book to be about one overarching thing, it’s freedom,” Prince writes. “And the freedom to create autonomously.”

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link