[ad_1]

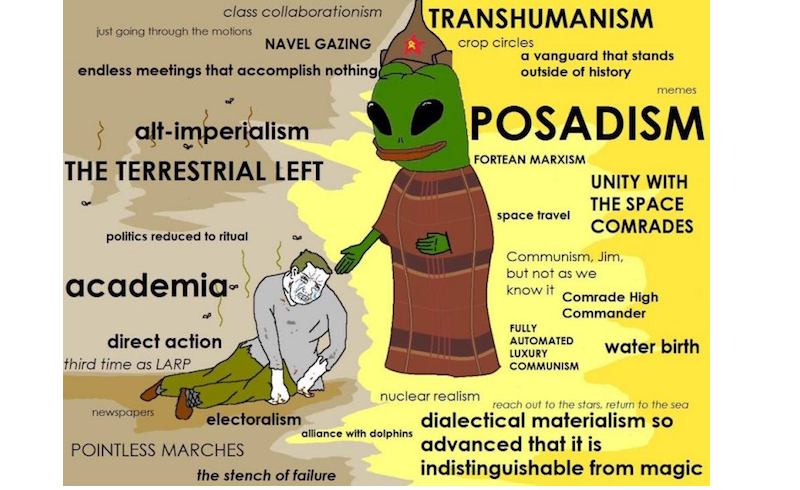

In the 1960s, the Argentine Trotskyist known as J. Posadas led an idiosyncratic socialist movement that embraced science-fictional ideas about nuclear war, UFOs, and interspecies communication. After his death in 1981, Posadism was virtually forgotten. But a few years ago, memes devoted to this obscure advocate of catastrophic communism began proliferating in leftist corners of social media. In one, a white-haired Posadas dons a pair of Morpheus sunglasses, inviting us to take the “gently glowing green pill.” Another detourns a drawing of ape-to-human evolution, charting a progression from Hegel to Marx to Posadas to, finally, the fully evolved extraterrestrial. Taking the memeification of Posadas as a point of departure, journalist A.M. Gittlitz’s book I Want to Believe: Posadism, UFOS, and Apocalypse Communism looks back at the history of Posadism to explore why this largely discredited movement has elicited so much recent interest. Though the memes adopt a tone of irony and ridicule, Gittlitz senses that they express something more: a desire among young radicals to understand an unqualified, lifelong commitment to a revolutionary project, regardless of how strange the path forward might become. Despite the image of the Posadists as “brainwashed Bolsheviks or socialist Scientologists,” they were sincere in their dedication to class struggle and their certainty that revolution was coming—a belief that today arguably seems no less farfetched than the existence of UFOs.

Pluto Press

Posadas was the nom de guerre of Homero Cristalli, a working-class militant, who, after an impoverished childhood and a short soccer career, found his place among the haughty Trotskyist intellectuals in Buenos Aires, in the late 1930s. He brought the proletarian experience that they pontificated about, and they brought the books and the theory. He started off as revolutionaries often do, organizing unions, leading strikes, and showing up for the study group, and climbed through the ranks of the Fourth International (an international socialist organization founded by Leon Trotsky and his followers in 1938 as an alternative to the Stalinist Comintern). In 1951, Posadas and the Uruguayan militant Alberto Sendic were put in charge of the Latin American Bureau (BLA), an organization that oversaw all Trotskyist activity in Latin America. Under their leadership, the BLA spearheaded revolutionary actions throughout the continent, organizing cadres involved with the revolution in Cuba, the guerrilla wars in Guatemala, and other uprisings throughout the Americas.

By the early 1960s, however, a bizarre turn was afoot. Posadas began to demand excessive discipline from his followers, including austere living conditions and prohibitions on nonreproductive sex, homosexuality, and abortion. He also moved to take leadership of the entire Fourth International, claiming that Third World insurrection now represented the front end of history on the way to a socialist world. Someone like himself, from the Global South and seasoned in struggle, should lead, and the politically stagnant European and North American workers’ movements should follow. Though this might have been a reasonable argument, it was delivered through erratic screeds. In 1962, Posadas and his followers broke with the Fourth International, soon declaring their own rival movement.

Posadas adopted a number of extreme positions that seem patently absurd today, chief among them his embrace of nuclear war. He proclaimed that the Soviet Union should preemptively strike the United States, based on the belief that a socialist world order would arise from the radioactive ashes. The logic behind this belief, familiar to any vulgar Marxist, was that history was inevitably unfolding toward communism; a nuclear holocaust would only hasten the transition. He is, however, most notorious for his pronouncements on extraterrestrials. At a 1967 meeting, Posadas delivered a speech in which he discussed UFO sightings and extraterrestrial life, speculating about the existence of beings capable of harnessing “all the energy existing in matter.” Organizations like NASA, he argued, were limited by a capitalist mindset oriented around private property; any species advanced enough to develop the technology for intergalactic travel would necessarily have evolved beyond, or bypassed, capitalism. One day, perhaps, they could be called upon to help resolve struggles on Earth.

Gittlitz suggests that the speech was intended primarily to placate Dante Minazzoli, one of Posadas’s closest comrades and a dedicated ufologist, but Posadas’s megalomania still compelled him to disseminate a transcript of the remarks in Posadist publications worldwide, under the title “Flying Saucers, the Process of Matter and Energy, Science, the Revolutionary and Working-Class Struggle, and the Socialist Future of Mankind.” Other unusual claims followed: after the birth of his daughter, Homerita, in 1975, he became preoccupied with strange pedagogical exercises and research into dolphin telepathy. As a result, the Posadists were cast as a space cult seeking contact with aliens, the predominant image of them that we have inherited today. While many of these theories and statements seem ridiculous, Gittlitz situates Posadas’s catastrophism within its historical context, a period marked by the escalating nuclear arms race and the Cuban missile crisis: even Che Guevara said he was willing to embrace the mushroom cloud if it would advance the cause of socialist revolution. Similarly, Posadas’s speech about UFOs coincided with attempts by respected scientists like Carl Sagan to locate and contact other intelligent life forms in our galaxy.

As Gittlitz’s research shows, Posadas’s ideas may not have been so out of tune with the historical moment in which he was living, but his movement took on an increasingly cult-like quality. After several months in a Uruguayan prison in the early 1970s, Posadas settled in Italy, organizing a compound for his inner circle to live communally. He eventually expelled veteran militants—including his own wife—and gathered around him young recruits with little organizing or political experience. Another world was coming, Posada began to preach, in which the separation of animate and inanimate worlds, the cosmos and humanity, would be abolished. It would be a world in which human lifespans would be extended, interspecies engagement would be flourish, aliens would make contact, and the need for jokes would disappear.

At a time like ours, when the language of revolution has been co-opted by ethnonationalists, political reactionaries, and corporations like Space X and Amazon, what does Posadas offer? His wacky ideas hardly seem useful in combating the impoverishment of our political discourse. But Gittlitz shows that their return to circulation is not without some merit. The revival of Posadas is part of a broader recuperation of “eccentric” figures who were exiled from the history of communism, among them Victor Serge, Alexander Bogdanov, Nikolai Fyodorov, and Hugo Blanco, based in the notion that these discarded figures might offer a way to revitalize the communist project without repeating the debacles of the twentieth century. What we can take from Posadism isn’t a belief in UFOs and core meltdowns, but the lunacy of optimism: the ability to imagine a politics guided by the needs of the weakest among us, a desire for more future and less past, and a willingness to leap into the unknown instead of opting for the shitty sure thing.

[ad_2]

Source link