[ad_1]

Pearl Pearson Jr. was driving home from a Starbucks in Oklahoma City in 2014 when he noticed police lights flashing behind him. Oklahoma Highway Patrol troopers suspected him of being involved in a hit-and-run, but Pearson — a then-64-year-old Deaf Black man whom his daughter described as “gentle and kind” — had no idea why he was being pulled over.

He parked his car and placed his hands on the steering wheel as a trooper approached his vehicle with a gun drawn. Pearson couldn’t hear what the trooper was saying and reached for a placard he kept in his car that explained his disability. But before he could grab it, the trooper punched him in the face.

Pearson was dragged from his car, severely beaten and put in a chokehold; one of his arms was ripped from its socket. He experienced brain and eye damage from the encounter, but he survived.

Deborah Danner was a 66-year-old Black woman with schizophrenia. In 2016, an NYPD officer shot her in her Bronx apartment while responding to her neighbor’s call that she had been behaving erratically. She did not survive.

Chillingly, Danner wrote an essay four years before her death about the dangers of people with mental health conditions interacting with police that predicted her fate.

“We are all aware of the all too frequent news stories about the mentally ill who come up against law enforcement instead of mental health professionals,” she wrote. “And end up dead.”

The circumstances of Danner’s death echo those of Breonna Taylor’s. Louisville, Kentucky, police officers shot the EMT eight times in March after bursting into her home on a “no-knock warrant” related to a drug investigation.

Pearson’s story shares DNA with so many other stories about police violence toward Black people at traffic stops, like Philando Castile and Maurice Gordon.

Yet conversations and media coverage surrounding both Pearson and Danner’s cases zeroed in on their disabilities and largely treated their race as irrelevant.

Conversely, prominent victims of police brutality like Sandra Bland, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Elijah McClain and Tanisha Anderson all had disabilities or underlining health issues that may have played significant roles in their deaths — yet these aspects of their identities tend to get glossed over.

In cases of police violence against Black disabled people, the media tends to focus on either the victim’s race or the victim’s disability, instead of examining the overlap between the two identities, said Vilissa Thompson, a Black disabled social worker and activist who is a consultant for the Movement 4 Black Lives. This gives the public an incomplete story.

The “erasure of people’s disabilities when we talk about them” is a major issue when it comes to Black disabled victims of police violence, Thompson told HuffPost. “Either the complete erasure or omission, or leaving it as a footnote and not understanding the connection between race [and] disability … and who is being disproportionately impacted within the Black and disabled communities.”

Both people of color and people with disabilities are more likely to come in contact with law enforcement. And both groups have higher chances of negative things happening as a result.

Britney Wilson, a Black disabled civil rights attorney

There is no reliable national database tracking how many Black disabled people experience and die from police violence. In fact, there’s not even a public federal database tracking who dies in police custody in general. But the data we do have sheds some light on how the combination of being Black and disabled may have dire consequences when interacting with law enforcement.

In 2015, The Washington Post began work on a real-time database that tracks fatal police shootings. A 2016 report by the Post compared that data with the most recently available U.S. census figures and found that Black Americans were 2.5 times more likely than white people to be shot and killed by law enforcement.

And the Ruderman Foundation, a philanthropic foundation with a focus on disability advocacy, has estimated that one-third to one-half of all people killed by police are disabled.

The brutal killing of George Floyd has sparked nationwide protests and heated conversations about racial justice and police violence over the past few months. But the issue of disability has been largely ignored, even though disability can increase a person’s risk of death or injury by police, especially if that person is also Black.

For instance, the movements and actions of disabled people can be misinterpreted as out of the ordinary or threatening to law enforcement.

Heather Watkins, a Black disabled activist based in Boston, gave the example of how police could easily misinterpret the speech patterns of someone who has cerebral palsy.

“[If] they’re talking, then someone might consider them drunk,” Watkins said. “I’ve had friends who have cerebral palsy that say that they’ve been targeted for appearing inebriated.”

Police interactions can turn dangerous when a disabled person cannot immediately respond to an officer’s demands for compliance the same way that a non-disabled person would. And when law enforcement’s default is to respond violently to someone who doesn’t immediately obey demands, a disabled person is certainly at risk. For a Black disabled person, this risk is compounded by biased officers’ perception of them as more threatening than non-Black people.

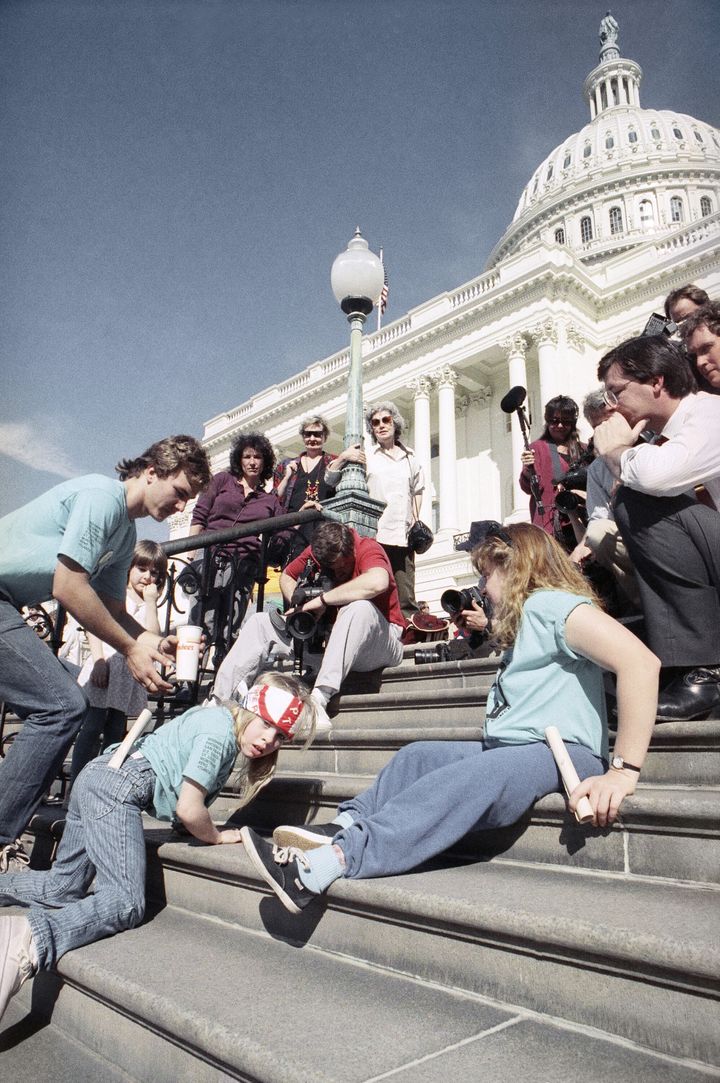

Disabled people also often face indifference ― from police, courts and the general public ― about the legal rights afforded to them by the Americans with Disabilities Act, which prohibits discrimination against disabled people, including discrimination by police.

“I’ve been in court cases where lawyers — police brutality lawyers — had no clue about the Americans with Disabilities Act,” said Leroy Moore, a Black disabled activist who is the chair of the Black Disability Studies Committee for the National Black Disability Coalition. “The ADA doesn’t count in court cases around police brutality. And if it does, it gets thrown out constantly.”

Black Americans are five times as likely as white Americans to say they’ve been unfairly stopped by police because of their race, according to a 2019 Pew survey.

Disabled people also wind up encountering police even though they are not posing a threat. They get the cops called on them for what others perceive as strange behavior or by family, friends or neighbors requesting so-called wellness checks on their mental health condition. In numerous instances, these situations have ended up deadly for people with disabilities.

“Both people of color and people with disabilities are more likely to come in contact with law enforcement,” said Britney Wilson, a Black disabled civil rights attorney. “And both groups have higher chances of negative things happening as a result.”

Lisa “Tiny” Gray-Garcia, founder of Poor Magazine and a self-described “formerly houseless incarcerated” person, told HuffPost that the tendency to silo a victim’s identities is “absolutely idiotic.”

“The connection or the intersectionality of disability, racism, white terrorism and poverty are almost always interlinked,” she said.

Black Americans are, in fact, more likely than white Americans to be disabled, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Due to centuries of systemic racism, Black Americans tend to make less money and therefore are more likely to live in less affluent neighborhoods. These communities often have worse access to health care, worse access to healthy food, worse air quality and other environmental factors that contribute to residents developing disabilities, mental health conditions and other health issues.

Black Americans also often don’t have access to unbiased medical and mental health care. Because of this and the barriers to health care in general, disabilities and other health conditions that Black Americans develop can go undiagnosed and untreated.

And the fight for justice is harder when Black disabled people feel they are not fully accepted by either the Black or the disability community.

“We don’t feel safe in either community because we experience harm by both communities,” said Thompson, who created the Twitter hashtag #DisabilityTooWhite four years ago. “In many ways, where do we belong? We have the disabled community where the white folks or non-people-of-color can be anti-Black or racist, and you have the Black community where Black folks are ableist. So where do we (A) fit? And (B) feel safe enough to even proclaim that our lives matter too?”

If you want me to go back to the slave trade, we were brought here based on our ability to produce. That’s something that inherently links race and ability. That’s the function of capitalism, it’s instinctively and intrinsically tied to race and ability.

Britney Wilson

Thompson said she’s experienced racism from white disabled activists.

“They feel if you talk about anything other than disability, you’re taking away from the movement and it’s a distraction,” she said. “I think that a lot of white disabled people are not comfortable with understanding and knowing that they have white privilege even though they’re also disabled. So I think there’s a reckoning internally with many of them in seeing how you can be the oppressor and be oppressed at the same time.”

There’s also a stigma against disability within the Black community, which Wilson attributes in part to centuries of oppression.

“If you want me to go back to the slave trade,” she said, “we were brought here based on our ability to produce. That’s something that inherently links race and ability. That’s the function of capitalism, it’s instinctively and intrinsically tied to race and ability,” Wilson said. She also discussed this idea in a 2016 article she wrote for The Nation.

“When you already have one societal strike against you,” Wilson said, referring to race, “who’s going to sign up for two?”

Proposed solutions to police brutality ― both against Black disabled people and in general ― are wide-ranging, and advocates often don’t agree on what strategies are best.

Gray-Garcia and Moore, who work closely together through Poor Magazine, stressed the importance of people not calling 911 about behavior they may perceive as suspicious.

“Most humans in the United States have been told that the way to solve all their problems is to call those three numbers,” Gray-Garcia said. She described a situation in which an Indigenous man died in police custody after someone called 911 to report he was having a mental health crisis on the streets.

“The reality is somebody called those numbers because they wanted to, quote, ‘help him.’ Their heart wasn’t necessarily wanting to get him killed. But that’s the system we have.”

Some initiatives aimed at decreasing police violence, particularly toward people with disabilities or mental health issues, include programs to enhance police training or to redirect some 911 calls to other kinds of responders.

The White Bird Clinic in Eugene, Oregon, for instance, runs a program called CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets) that redirects non-emergency 911 calls that involve mental health, substance abuse and homelessness to a team of medics and crisis-care workers.

The Arc, one of the country’s largest disability rights organizations, launched its own program in 2015 that teaches criminal justice professionals how to identify people with disabilities in order to interact with and accommodate them better.

But not everyone agrees these reforms are enough. Gray-Garcia and Moore argue that solutions focused on better training for law enforcement won’t work and believe the police should be disbanded entirely.

“Let’s expand our search for models and talk about actual livable models without the police when we’re having this conversation,” said Gray-Garcia, pointing to efforts outside the U.S.

Both also think that in order to combat police violence, American society needs to grapple with a myriad of issues facing marginalized communities.

“There’s not one big answer for everything. It’s the small things that are going to make it happen,” Moore said. “So there’s the solution ― educating the community about mental health, about disability, about the ADA, about being a neighbor, about reshaping your disabled neighbor as a person.”

Gray-Garcia underscored that the situation is messy and it will take all people — regardless of race, ability, gender or class — to do the hard work needed to create change.

“It’s a mind shift,” she said. “It’s not a simple answer. And that’s the hardest part. Because you’re looking for a nice clean line for your story. But … it’s a complicated, multilayered process of unpacking 527 years of genocide, lies, racism and murdering. You do not get over that in one day.”

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link