[ad_1]

Pierre Bonnard, Fenêtre ouverte sur la Seine (Vernon) [Window Open on the Seine (Vernon)], 1911–12, oil on canvas.

MURIEL ANSSENS/VILLE DE NICE MUSÉE DE BEAUX-ARTS JULES CHERET

With a major exhibition of Pierre Bonnard’s work having opened earlier this week at Tate Modern in London, we turn back to the Summer 1948 issue of ARTnews, which featured an essay by John Alford about the French painter written on the occasion of a memorial exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (Bonnard died the year before, in 1947.) Alford’s essay addresses the stylishness of Bonnard’s work, noting that in his paintings, “the impact of form, color, and luminosity are such as we can only experience at rare moments of hypersensitivity, when time, it seems, stands still.” The essay follows in full below. —Alex Greenberger

“Bonnard’s art for art’s sake”

By John Alford

Summer 1948

Relating the works of this “last Impressionist” to nineteenth-century ideas in his exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art

The first response of anyone visiting the memorial exhibition of the paintings of Bonnard now on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York will depend on the habits of mind of the observer. Most people will respond almost certainly to the vibrant but harmonious color of the pictures. The effect is of a light-filled space in which chromatic and linear patterns excite the senses as they are excited when going from a cool room into the glow of a hot afternoon in early summer, before the grass has seared and the leaves have taken on the flatter opaqueness of August. It is tremendously sensual, with an impact that affects not only the eyes, but the dilations of veins and the nerve-ends of the skin. To that degree the art of Bonnard is “abstract.” It creates a patterned stimulus to which we respond primarily with our senses, without identifying the source of excitation as a person, a house, a flower, or a tree.

But Bonnard’s painting is also concrete and representational, and it is quite possible that someone of more socially determined habits would first be aware not of the chromatic orchestration, but here are the interiors of rooms; scenes of family breakfast with bread and fruit and gay checkered line; views from open windows into gardens, or over suburban roofs with summer landscapes, with glimpses of river or sea.

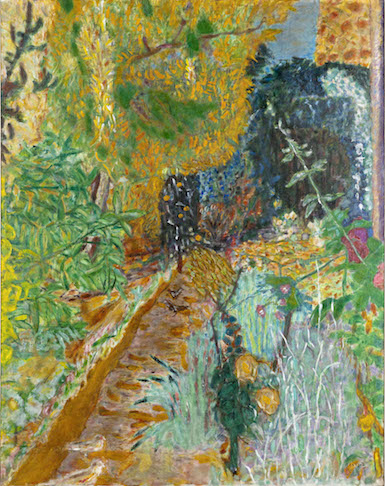

Pierre Bonnard, Le Jardin (The Garden), 1936, oil on canvas.

ROGER VIOLLET/MUSÉE D’ART MODERNE DE LA VILLE DE PARIS

Both observations are, of course, essential to a full understanding and enjoyment of his art. For, from first to last, it was fostered and determined by a sense of fragile well-being, by the love of a condition that was transitory either because of the mortality all organic life is heir to, or because of some sense of cultural culmination in the age in which he himself matured. More than a painter of domestic contentment, Bonnard is a painter of domestic love, not concentrated on a single person nor a group of people who by ties of blood he could call his own (though such an element is present in his observation of the children of his sister, Andrée Terrasse), but of a domestic love suffusing all elements of a pattern of life which he had good fortune to inherit and the skill to bring into being again in his imagination and by his craft.

Bonnard painted many “still-lifes” of fruit. But his fruit is never simply form and color, an ideal of abstract organic order, as it was with Cézanne. It is fruit that has the warmth of the sun on it; that is going to be velvety to the touch and cool and sweet in the mouth. It is part of the anticipation of getting up in the morning and of coming in from the garden for lunch; of going out again to cultivate or to pick for the next domestic meal. For though the subject of his painting may be merely a bowl of fruit, his theme is always the order of a sensuous and self-disciplined pattern of life.

His sensuous intensity, which was both personal and of great cultural significance, suggests that Bonnard was aware in some measure that the way of life he painted was under threat of dissolution. His art, in fact, is related to a particular moment in the history of French culture and of Western civilization. The praise of urban and domestic order was not at all new either in European or in Oriental art. It is the theme of Jan van Eyck’s portrait of Jan Arnolfini, and of Carpaccio’s Dream of St. Ursula. It is inspired Vermeer’s View of Delft and countless Dutch interiors. Watteau, doubly prescient, harps endlessly on its fragility. Chardin, for whom the bowl of fruit had the same significance as for Bonnard, lingers over it with patient affection. The English “conversation” painters of the eighteenth century treat it with an ostentatious assurance. But in the first half of the nineteenth century it disappears with the Romantic flight from urban actuality. Whatever the creators of the new industrial order thought of “self-help” and laissez-faire, the art they fostered and patronized shows little sensuous affection either for the new artifact shell or for the new mechanical disciplines they were bringing into being.

The greatest critic of the new drabness and of the ledger mentality of industrialized commercialism was Baudelaire, with his gospel of sensory and emotional vividness at any cost; the gospel of heroic humanism even if it must be achieved in Flowers of Evil. But the best known document in English expressing the critical doctrine, is the conclusion to Pater’s volume of papers on The Renaissance. That essay, written in 1868, is an astounding exposition of what was to become common practice in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. In it, he comments on the dissolution under scientific analysis of the objects we familiarly identify as permanent forms, into perpetually changing elements and forces not available to direct sensory observation; and on the similar dissolution of what we assume to be our permanent personalities or minds into an evanescent pattern of sensations or “impressions” finally disrupted and ended by death. “Our one chance” was to cultivate the vivid moment. “Great passions may give us this quickened sense of life . . . only be sure it is passion.” “Of such wisdom . . . the desire of beauty, the love art for its own sake has most. For art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments’ sake.”

Pierre Bonnard, The Studio with Mimosas, 1939–46, oil on canvas.

PHOTO: ©CENTRE POMPIDOU, MNAM-CCI DIST. RMN-GRAND PALAIS/CENTRE POMPIDOU

The relation to Impressionism of this concentration on the quality of the transitory moment, in both its objective and its subjective aspects, is clear enough to need amplification here. For Baudelaire, it was already part of the characteristic structure of “modern” culture, as is explicit in his essay on the urbanity of Constantin Guys. And for the Impressionists, too, the spectacle of the dance hall and the theatre, the animation of picnics and race-courses, the bustle of the streets, the drift of smoke in railway stations are as frequent and characteristic types of stimulus as the shifting pattern of tones in landscape and sky. On these terms the city and urban culture are readmitted to the imaginative repertory of the creative artist. For a couple of decades or more the sensory aesthetics of Impressionism and the doctrine of art for art’s sake are inextricably interwoven. The alliance, however, was more an accident of history than a result of any necessary limitation in the creative process of the artists. Within a few years art for art’s sake had degenerated to the charming trivialities of Whistler’s Nocturnes and the smart-alec epigrams of Oscar Wilde. But Impressionist painting, though it is essentially an art of momentary record, is great art precisely when and because it is something more. The cultivation of the quality of the passing moment “simply for those moments’ sake” is actually the negation of great passion. Great passion is always concentrated on future ends of a stable and funded kind; on self-realization, on social and economic security, on the security of love in which the whole personality, including but not limited to the senses, is involved. That is why Toulouse-Lautrec, with his sordid sincerity—his real “flowers of evil”—is potentially a more intense and more moving artist than the detached Degas. And again, this moral inclusiveness is what gives the sense of an intimate, sensuous human order, to so many of the great paintings of Renoir.

The enjoyment of such painting is not simply the enjoyment of art for art’s sake, nor only of “moments as they pass and simply for those moments’ sake,” but also of the achievements of at least some of the basic purposes of human endeavor, with its essential disciplines and codes. For, though the purpose of such painting is not practical morality, it touches our interest at points where moral tension makes both artist and spectator are most aesthetically alive. The point is one around which criticism has been revolving for a century and on which it has still reached no stability. But it is fundamental for an understanding of the painting of Bonnard.

A perception of the weakness of Impressionist aesthetics led to the secession of both Cézanne and Gauguin, and it is significant that Bonnard started his artistic career in the shadow of Gauguin’s “synthesism” and in relation with the Nabis group. Less of an intellectual than Sérusier or Maurice Denis, more balanced and serene in temperament than Gauguin, his adherence was tentative and temporary. Yet his habitual procedure in painting was closer to theirs than it was to that of the Impressionists, whose “instantaneous” quality Bonnard so strongly recalls. Like Degas in his old age, he never drew from the model, but would watch and absorb and filter his impressions till an image crystallized to express the character of what he loved. If it was Gauguin’s intention to concentrate “all Tahiti” in a single image, Bonnard did this for his cultural environment, and with less ado.

Pierre Bonnard, Le Café (Coffee), 1915, oil on canvas.

TATE

Among the gestures of Gauguin, rebellious against the encroaching commercialism of his age, was his intermittent practice of the decorative crafts. Bonnard, too, in his youth, was more than touched by the ripples of the “art and craft” movement and by the prevalent cult of Japonaiseries. The roots of the habit flowers in more than Bonnard’s occasional screens and illustrated books. The life he records is suffused not only with the sense of domestic well-being, but with an equally strong sense of domestic “well-making,” of man’s functional and affectionate relation with the earth and its materials. The love of craftsmanship issues in the quality of all his painting, and is much more than decorative craftsmanship. It is part of the commentary on the Paris of the nineties and of the series of records of the intimacies of the house and the garden, the kitchen and the table. The furniture hardly needs the visible presence of the user to make its humanity immediately apparent. Indeed in a number of his canvases one’s discovery of the human figure is subsequent to one’s imaginative seizure by a patently domestic moment among food and crockery, or among the tables and chairs of a garden terrace. Bonnard’s serenity floated not seldom on a humor that was untouched by any sort of malice. In his old age, as the intimates of his own generation died, these things, and the nude human figure, and the humanized landscape of Le Cannet, remained as symbols of a culture that was also passing.

The quality of transience in Bonnard’s imagery is unique. For where, as in the work of Monet, it is recognized by an insistence on the momentary effect of atmospheric light, and in that of Degas by an attitude caught in transition from one posture to another, in the paintings of Bonnard it is not merely the movement of light or of a figure that have been arrested, but the whole passage of time. This is due, I think, to a combination of a highly sophisticated use of the Impressionists’ tricks of candid camera attitudes and of composition, with an extreme vividness of sensory quality. Monet recorded each season of the year and each hour of the day. With Bonnard it is always spring or early summer and high noon. But the impact of form, color, and luminosity are such as we can only experience at rare moments of hypersensitivity, when time, it seems, stands still. This is emphatically a savoring of the “quality of the moments as they pass,” but equally emphatically not merely “for the moment’s sake.” For the moment itself is both a symbol and a fruit, which in turn has a seed and a flower and fruit, as in all processes of growth and maturation.

In connection with the Bonnard retrospective, the Museum of Modern Art has published a catalogue of the exhibition with a long biographical and critical essay by John Rewald; 109 reproductions of paintings, drawings, and prints; and five colorplates. Distributed by Simon and Schuster, New York, it sells for $5.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 1948 issue of ARTnews on page 17 under the title “Bonnard’s art for art’s sake.”

[ad_2]

Source link