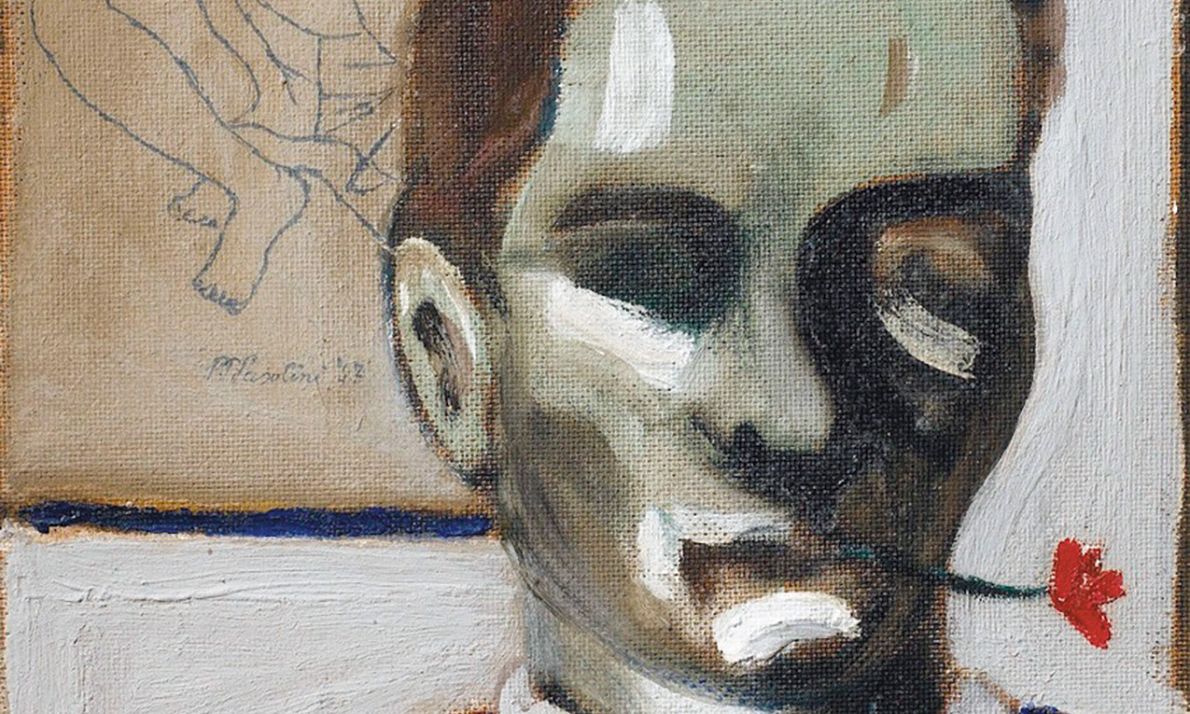

An intermittent painter: Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Self-portrait with flower in mouth (1947) © Gabinetto Scientifico Letterario G.P. Vieusseux; Florence. Courtesy Galleria d’Arte Moderna Rome

Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-75)—poet, filmmaker and a prolific journalist with stinging opinions—was a celebrity in Italy and beyond, thanks to an acerbic pen and films that included Mamma Roma (1962) and The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964). After he was murdered in Ostia near Rome in 1975, a court found that the killing was not for anything he wrote or produced, and convicted a youth from the rough trade where Pasolini sought sex.

Pasolini painted intermittently and said art was one inspiration for his films. In a photograph on the book’s cover, he poses with a carnation stem clenched between his teeth as he stands in front of his self-portrait—same pose, same flower. It’s a study in self-assurance.

Heretical Aesthetics: Pasolini on Painting is an eclectic and fragmentary mix of his writings: spirited, polemical, personal and contrarian, often mordant. (The branding of Pasolini as a heretic predates this volume with the 1988 collection of his essays on film and literature, Heretical Empiricism.)

Massimo Listri’s Photograph of Pasolini before his self-portrait (1973) © Massimo Listri

Studying in Bologna with the art historian Roberto Longhi (1890-1970), a champion of Piero della Francesca, Caravaggio and Cézanne, Pasolini was too shy at first to approach Longhi and never completed his degree. He recalled his teacher’s critical rigour: “Back then, in the wartime winter of Bologna, he was simply the Revelation,” Pasolini wrote. “He always limited himself strictly to the internal logic of forms. The stakes were thus always high. Hence his caution, and his irony.”

Longhi introduced Pasolini to the light of Caravaggio’s “separate universe”, the former pupil wrote in 1974, “a process brilliantly accounted for by Longhi’s hypothesis that Caravaggio painted while looking at his figures reflected in a mirror”. Pasolini continues: “Such were the figures that he [Caravaggio] had chosen according to a certain realism: neglected errand boys at the greengrocers, common women entirely overlooked, etc … everything in the mirror appears suspended, as if by an excess of truth, of the empirical. Everything appears dead.”

The same could be said of Pasolini’s Mamma Roma, a family tragedy set in the slums of Rome. Pasolini bristled when critics saw Andrea Mantegna’s Dead Christ (around 1480) in a teenager’s corpse in the film’s final scene, declaring: “Mantegna had nothing to do with it. Nothing! At All!” He invoked his teacher: “Dear Longhi, please say something. Explain how foreshortening a body and placing the soles of its feet toward the camera doesn’t suffice to speak of Mantegna’s influence. Are they blind?”

Pasolini never warmed to abstract painting, echoing Palmiro Togliatti, leader of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), who also scorned the paintings of Giorgio Morandi—“full bottles, empty bottles and ghosts of bottles”. Yet Pasolini admired Morandi, and uttered political heresy in his poem Picasso (1953), questioning Picasso’s kitsch 1950 work Dove in Flight, which the PCI reproduced with a hammer and sickle on its membership cards. Communists were proprietary about Picasso, then a dutiful party member. In 1953 Rome was the site of the largest Picasso exhibition mounted to date. Pasolini wasn’t charmed: “He comes out / among the people, and gives in a time that does not exist: / feigned through the tools of his own old / fantasy. Ah, this merciless Peace / of his, this idyll of white orangutans, is absent from the people’s sentiment.”

The art historian T.J. Clark writes in the preface to Heretical Aesthetics: “Pasolini’s Marxism proved, in his lifetime, hardly more popular on the left than on the right. Processions of Marxist mediocrities reassured the faithful that the filmmaker was a bad Marxist. They still do. As if badness had not always been the point.”

More to Pasolini’s political taste, say the book’s editors Ara H. Merjian and Alessandro Giammei, were regional “dialectal” cultures, rooted in the local speech (stigmatised by “proper” Italians as “dialect”) in rural Friuli, where he grew up, or in the slums of Rome, where obscene local talk required translation for many Italians. Pasolini was drawn to Friulian painters, notably Giuseppe Zigaina (1924-2015), who was an adviser to Pasolini on his film Teorema (1968), a satirical allegory concerning a rich family falling apart, whose depressed teenaged son throws paint on surfaces, like Jackson Pollock.

Jargon-heavy but full of context, the collection ends with Pasolini’s thoughts on Andy Warhol from 1975. Italy was suffering from an encroaching sameness, fed by consumerism and commercial television, Pasolini thought, yet the United States seemed to be leading the way, with artists like Warhol exploiting that trend. In the catalogue for Italy’s first major Warhol exhibition, Pasolini observed: “I have before me Warhol’s silkscreen prints and several paintings. The impression they give is that of a fresco depicting various isocephalic figures, all of them, of course, posed frontally. The figures are iterated to the point of losing their individual identities and becoming, like twins, recognizable only by virtue of their clothing’s color.” It was one of the last things Pasolini wrote.

Alessandro Giammei and Ara H. Merjian (eds), with preface by T.J. Clark, Heretical Aesthetics: Pasolini on Painting, Verso Books, 224pp, $24.95/£16.99 (pb), published 1 August

• David D’Arcy is a correspondent for The Art Newspaper in New York