[ad_1]

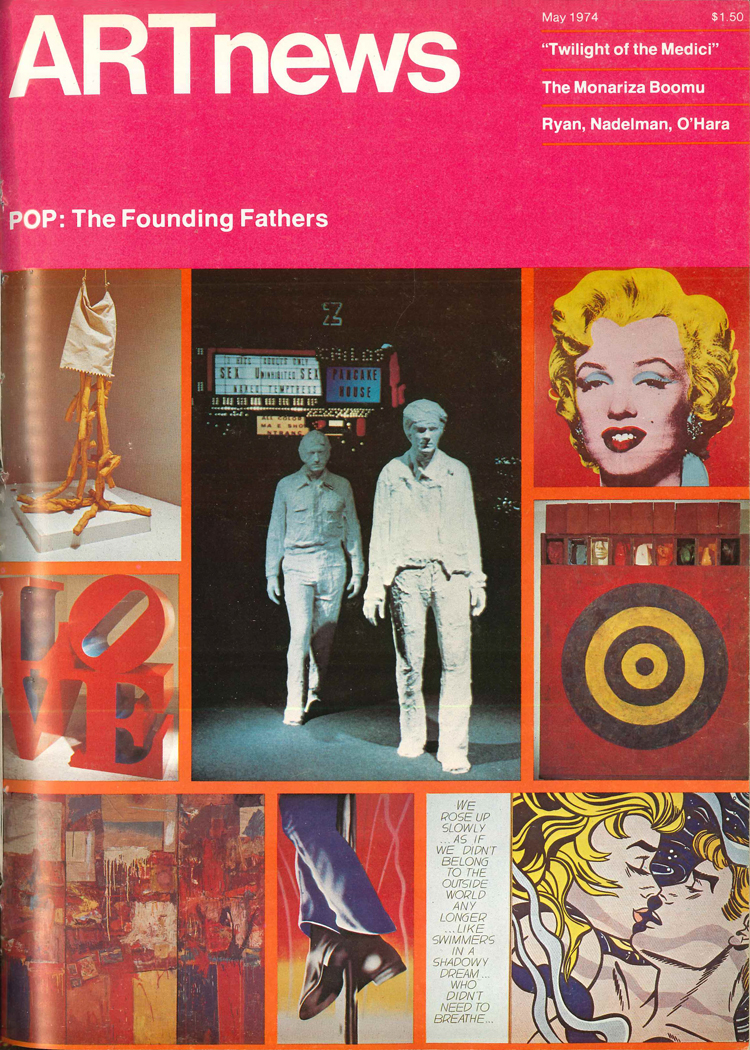

The cover of the May 1974 issue of ARTnews.

©ARTNEWS

In 1974, ARTnews contributor Phyllis Tuchman considered the careers of Pop artists George Segal, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Robert Indiana, interviewing each artist separately and asking questions about their practices. Writing ten years after the magazine’s publication of a series of interviews titled “What is Pop Art?”, Tuchman noted, “These artists are now in their forties. Their art has flourished, their thinking matured.” In her conversation with Indiana, the artist—who died last Saturday at the age of 89—reflected on the enduring and unexpected popularity of his Love sculpture, the nuances of his art, and the poisoning of the American Dream. —Claire Selvin

“Pop! Interviews with George Segal, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist and Robert Indiana”

By Phyllis Tuchman

May 1974

PT: Were you accurate when you predicted Pop art would last for ten years?

RI: It turned out to be accurate. As a movement, it’s been a shade less than ten years since it had force and impact. Pop artists continue to be Pop artists (which was not the case with all Abstract Expressionists).

Why did you tilt the O in Love?

For the dynamics of the design. A straight O is static and not very interesting. That little nudge sets the calligraphy into a dynamic structure. It suggests a movement that’s unexpected in letters.

Did you realize the image Love would be received differently than Eat or Die or Hug?

When I did Love, I thought they were equal. I presumed it was one more word to fit into my visual vocabulary. I had no idea of what would happen. I’ve always been mystified that Eat and Die didn’t catch on the way Love did. I find Eat and Die much more fun than Love.

When I look at your painting Jesus Saves, should I have a picture of Jesus saving us?

It’s certainly not my intention for you to project that way. I assume everyone drifts into some kind of projection from their own experience. When I look at Jesus Saves or think about it, what comes into my mind is immediate inspiration for the painting which has nothing to do with history or religion. One day my helper came in wearing a T-shirt made in Portugal that said, “Jesus Saves.” It was such a beautiful image—this workman on a hot summer day in New York wearing such a strange legend—that I asked him to take off the shirt and started to paint it. I had painted Crucifixions; I can appreciate the more profound aspects of the subject, but I was not trying to be profound in this particular painting.

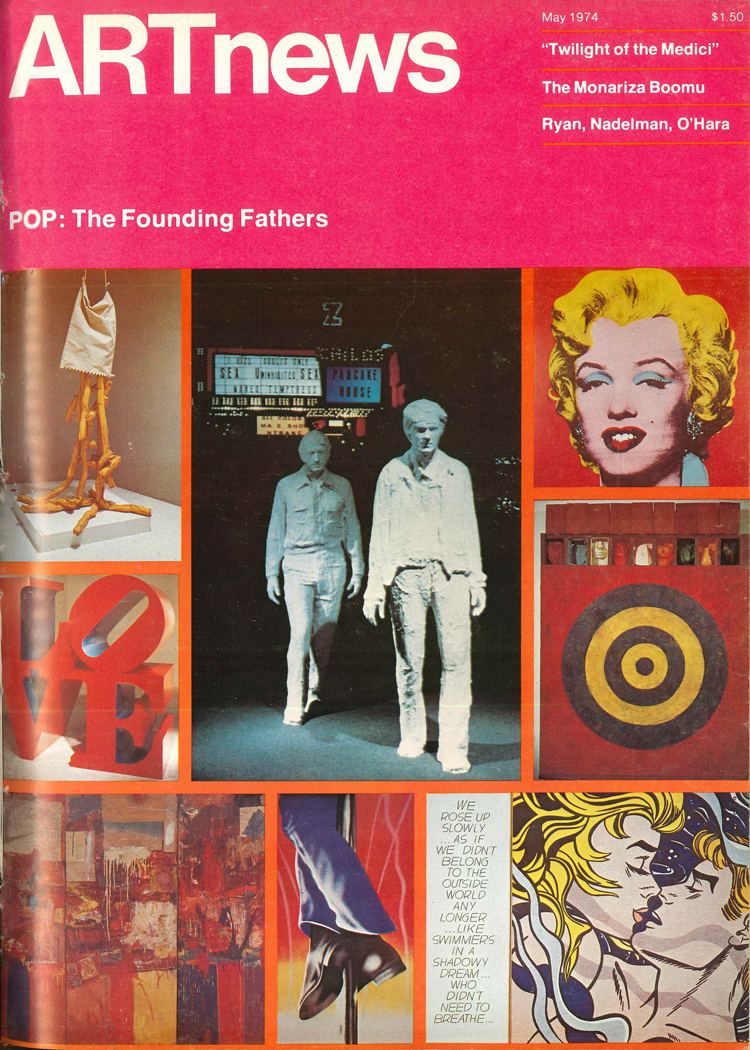

A composite of the original layout of this article in the May 1974 issue of ARTnews.

©ARTNEWS

How do you determine whether an object works or doesn’t work?

It’s always been a matter of impact: the relationship of color to color and word to shape and word to complete piece—both the literal and the visual aspects. I’m most concerned with the force of its impact. I’ve never found attractive things that are delicate, or soft or subtly nuanced. They’re not unattractive to others, but I’ve never found them attractive myself.

How did you arrive at your word constructions? Do you have models?

Material influenced content. The wooden beams were so narrow. I could not have long words. So my visual vocabulary became terse and telegraphic. The constructions have three-letter words; once in a while, they go to four or five.

Do you consider your constructions sculptures?

Yes. Basically, they’re stelae. They’re also herms. I had a great interest in classical art—the wood forms are based on the herm figure minus the heads. That came about gradually. They preceded my paintings. First the words appeared on the herms and then, as I began to be able to afford canvas and stretchers, the paintings happened—although they started out, as you can see, very small.

Do you use a different strategy for sculpture than painting?

My polychrome sculptures are more of a challenge. There’s more to do. My paintings are really rather simple and uncomplicated. Surfaces are easily arrived at. With my sculpture, I carved away relief letters; I bound the pieces in wires; I attached ropes and wheels. It’s just a more involving medium.

Do you still regard “the American Dream as optimistic, generous and naive”?

The American Dream has gone enormously sour. It has become the American Nightmare. The phrase “The American Dream” relates to something my father had. It wasn’t something I had. He had an American dream that turned out to be hollow. Given the war and what’s happening in Washington now, I think it is very difficult to be optimistic, innocent and naive. The dream aspect of the American character is probably all washed under now.

[ad_2]

Source link