[ad_1]

Piero della Francesca, Madonna del Parto, after 1457, Musei Civici Madonna del Parto, Monterchi, Italy.

EDISONBLUS, VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

THE EYE

The Eye: An Intimate Memoir of Masterpieces, Money and the Magnetism of Art, by Philippe Costamagna, New Vessel Press

NEW VESSEL PRESS

Who decides what’s real and what’s fake? How do they determine it? Who can be trusted?

In an anecdote- and evidence-rich book, Italian Renaissance art historian Philippe Costamagna reveals how he unravels truth and fiction through close observation, teamwork, accident, and good fortune.

Here is a brave, hearty defense of connoisseurship presented in a straightforward, frank, and even generous manner—and without jargon.

Like a good diagnostician, knowing by touch, experience, and instinct, more than by technology, whether there’s a disease, what it might be, and how it can be treated, an Eye—as such an investigator is known in the field—brings patience, experience, and intuitive skills to detection.

As Costamagna explains: “Unlike discoveries in mathematics, chemistry, or physics—those of Newton or Einstein, for example, which are the product of the genius of an individual—the discoveries made by the Eye have more in common with that of Christopher Columbus. No genius was required. Merely a spirit of adventure and a happy accident.”

An Eye must be able to view works in situ to properly examine subjects such as Piero della Francesca’s mural Madonna del Parto, which, requires climbing a steep hill up to the church, getting the keys from the grocer, turning on a lamp, opening a heavy door, and only then coming face to face with the centuries-old fresco to feel the “pleasure of discovery.”

This book is in large part a memoir. It is about the coming of age of a connoisseur—that is, an unbiased lover of art who has the patience, curiosity, and erudition to observe closely, be willing to fail, and in the process, make important accidental discoveries—and even a few mistakes.

Costamagna begins his modestly picaresque tale by tracing his privileged, Catholic upbringing in Paris whereby he says he learned to question “all received wisdom.” He traveled through Europe and the United States, as well as Tokyo, visiting provincial museums, galleries, banks vaults, and private collections. Something of a maverick, he proved his mettle up against more- and less-traditional experts, from academics to journalists.

Philippe Costamagna.

©2016 JF PAGA – GRASSET

Currently the director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Ajaccio, Corsica, he is the author of a book on the Florentine Renaissance painter Pontormo. He situates his tale in literary as well as art history. “It was only with Stendhal,” he writes, “that the two distinctive elements of modern art history, entertainments and erudition, finally came together.” Costamagna credits Stendhal with being “France’s first art historian,” noting that he “had read Giorgio Vasari and Luigi Lanzi, saw art and learned to appreciate it, then communicated his appreciation. His History of Painting in Italy (1817), Rome, Naples and Florence (1817), and A Roman Journal (1829) express this new way of looking at art.”

The novelist was also the source of the Stendhal syndrome, a psychological phenomenon whereby a viewer is overcome by the beauty or power of a work of art to such a degree that it leads to physical symptoms like crying or dizziness.

Costamagna found himself enthralled with a more-recent antecedent, as well, though he never met him. At the end of the 19th century, Costamagna notes, there were many attributions being called into question. “Amid such aesthetic and intellectual ferment,” he writes, “there arose a unique figure, that of Bernard Berenson.” He was one of the big three Eyes, along with the more traditional Roberto Longhi and the flamboyant, journalistic Federico Zeri.

Berenson, who came from an immigrant Lithuanian Jewish family, quickly made his way into New England society and eventually settled in Florence. A small, impeccably dressed man, Berenson—who cut a Henry James-ian figure, Costamagna observes—“is the true father of the modern Eye.” He credits Berenson with being much more than simply erudite. He was also “an expert at the crossroads of science, commissioned by museums and universities, and increasingly solicited by the art market.” Costamagna also defends him against charges of dishonesty and points out that Berenson himself had been duped by forgers.

As he was doing his research, Costamagna acknowledges, his “oldest passion” has been American museums, with their emphasis on world art. At the same time, however, he scoffs at American collectors who favor brightly restored works and glitz.

For his own part, we are fortunate enough to observe, he has been driven to follow a passion outside the money game of art.

Bruno Ceccobelli, Gran Pupilla, 2017, installation view, “Painting After Postmodernism,” 2018, at Reggia di Caserta.

LUCIANO ROMANO

Greenberg Post-Greenberg

As the years pass, rambunctious and pivotal art critic Clement Greenberg remains a polarizing and influential presence. Critic Barbara Rose, who herself had succumbed to his spell, now reckons with her “mistake.”

Herewith, my interview with her:

Barbara MacAdam: What conditions have changed since Clement Greenberg dominated art criticism?

Barbara Rose: The publication of Greenberg’s essays in Art and Culture in 1961 was decisive for a new generation of critics disgusted by the hyperbole and sloganizing typical of Harold Rosenberg and his epigones. I was an art-history graduate student at Columbia when David Rosand, a brilliant young Renaissance scholar interested in contemporary art, published Greenberg’s “How Art Writing Earns Its Bad Name” in his magazine The Second Coming. The clarity, consistency, and concrete philosophical basis of Greenberg’s critique of what Meyer Schapiro called “night-school metaphysics” impressed the most intelligent and well-educated young historians and became the point of departure for a new kind of criticism one might describe as formalist, although rigorous is more accurate. I began writing criticism to support my studies in Spanish Old Masters, and Greenberg was certainly my point of departure.

Nino Longobardi, Trimegisto, 1993, installation view, “Painting After Postmodernism,” 2018, at Reggia di Caserta.

LUCIANO ROMANO

BM: How has your opinion evolved?

BR: Rereading what I wrote in the early ’60s, I am aghast at how thoroughly I was mesmerized by Greenberg simply because he made sense when the rest of art writing seemed like puffery. I disagree with almost everything I wrote during the short time I bought in to Greenberg’s theories regarding flatness and opticality as the defining characteristics of advanced art. For example, today I would totally disavow anything I wrote about [Morris] Louis and [Kenneth] Noland, who appear to me now decidedly second-rate. The technique of staining thinned acrylic paint into raw canvas in order to unite the surface with the support was an obvious technical error, since those works are disappearing as the colors dim over time with the pigment literally sinking into unprimed cloth. I totally renounce what I wrote [about Louis’s veils] as a young, impressionable critic under Greenberg’s powerful influence. Looked at now, [they] appear sad, listless, and formulaic.

BM: What do you think is the future of painting? What effect will digital life/materials have on it?

BR: All I know is what I see in studios and what I see is individual experiments in style, technique, and materials. Most impressive to me are artists stretching the classical media—painting and sculpture—in new ways that are obviously affected by the world around us. I look for energy and originality and the internal need to go against the prevailing current, which, of course, is now the triumph of postmodernism and technology-based works using reproductive media. I was involved with the formative years of Experiments in Art and Technology with Bob Rauschenberg, Billy Kluver, Bob Whitman, and Robert Breer, and I continue to believe in its premise that technology can be used as a medium in the same sense as paint and canvas. But it is not a means of expression or of meaningful imagery. The greatest aesthetic use of technology remains film—not video but cinema.

BM: Any thoughts on who the next Clement Greenberg opinion-shaper might be?

BR: The problem is not that the emperor has no clothes. It is that there is no emperor. I read very little of what is called art criticism because it is really little more than undigested press releases. But I do read Roberta Smith, Holland Cotter, Barry Schwabsky, and Jed Perl. Although I may disagree with them, they are first-class writers and serious critics who have something relevant to say.

Installation view of “Painting After Postmodernism,” 2018, at Reggia di Caserta.

LUCIANO ROMANO

BM: Where do you plan to take your work?

BR: I am concentrating on finishing three books I’ve been working on for years. One is a memoir, one is a study of why Pollock virtually stopped painting, called The Last Days of Jackson Pollock, and the other is a study of the impact of the medieval Beatus manuscripts on modern art. Everything I write is based on documentation—not free association about what I think so-and-so was thinking. The decline and gradual disappearance of French theory is a huge relief, and an opening for fresh thinking about the art of the recent past.

BM: Are you still curating shows?

BR: Yes, my exhibition “Painting after Postmodernism” has been shown in three vastly different venues—the 1930 modern-style seven-story former department store the Vanderborgh in Brussels, the Rococo Palacio Episcopal in Malaga, Spain, and just now at the Reggia di Caserta, the extravagant 18th-century palace of the Spanish Bourbon kings of the Two Sicilies. Each installation was a different kind of challenge in terms of the relationship of the art to the architecture. It was a huge and probably crazy experiment I’m still recovering from.

The main thesis was a rejection of Greenberg’s definition of painting as exclusively addressed to the eye since all the paintings were involved with complex surfaces that stress not mechanical applications but the visible work of the hand and body. The show at the Reggia di Caserta includes nine Italian artists, several of whom, like Bruno Ceccobelli, Nino Longobardi, and Gianni Dessi, once had New York galleries. But since the Italian government doesn’t spend money promoting its great living artists, Italian painters hardly have a presence internationally. One lucky exception is Roberto Caracciolo, who has a show now at Loretta Howard gallery in New York. But he is half American and studied at the Studio School, so he has a permanent presence here. Howard also shows Larry Poons, who was in many ways the star of “Painting after Postmodernism.” Like me, Larry had his Greenberg moment, and like me, he managed to survive and define his own individual path.

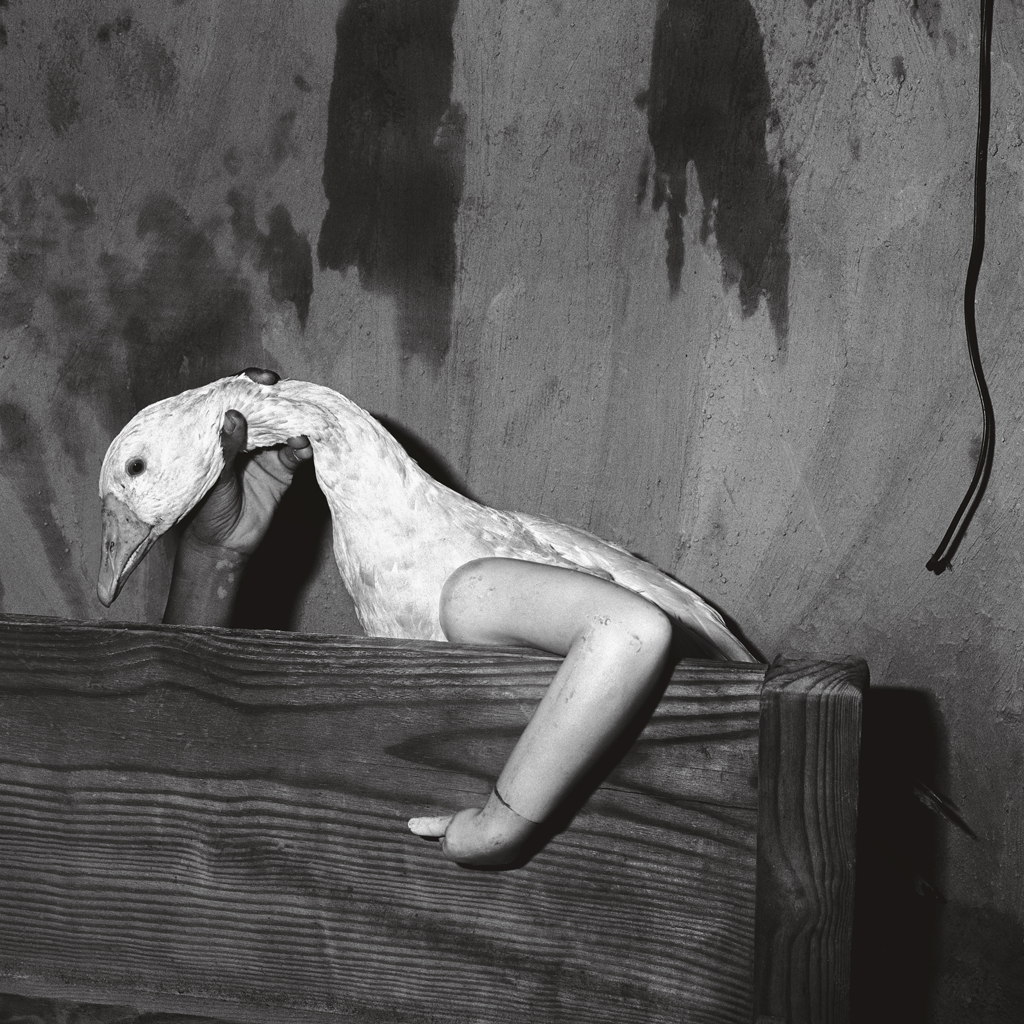

Roger Ballen, One Arm Goose, 2004.

©2017 ROGER BALLEN

Roger Ballen

South Africa–based, New York–raised photographer Roger Ballen has long been excavating and creating parallel worlds. His theater of photography probes the psyches of man and animal and the anomalies of earth. He continually stages his own autobiography. In a new book he calls a “retrospective,” Ballenesque (published by Thames & Hudson), he documents, traces, and analyzes his life, through words and images, making “concrete,” he told me, his mostly inner reality.

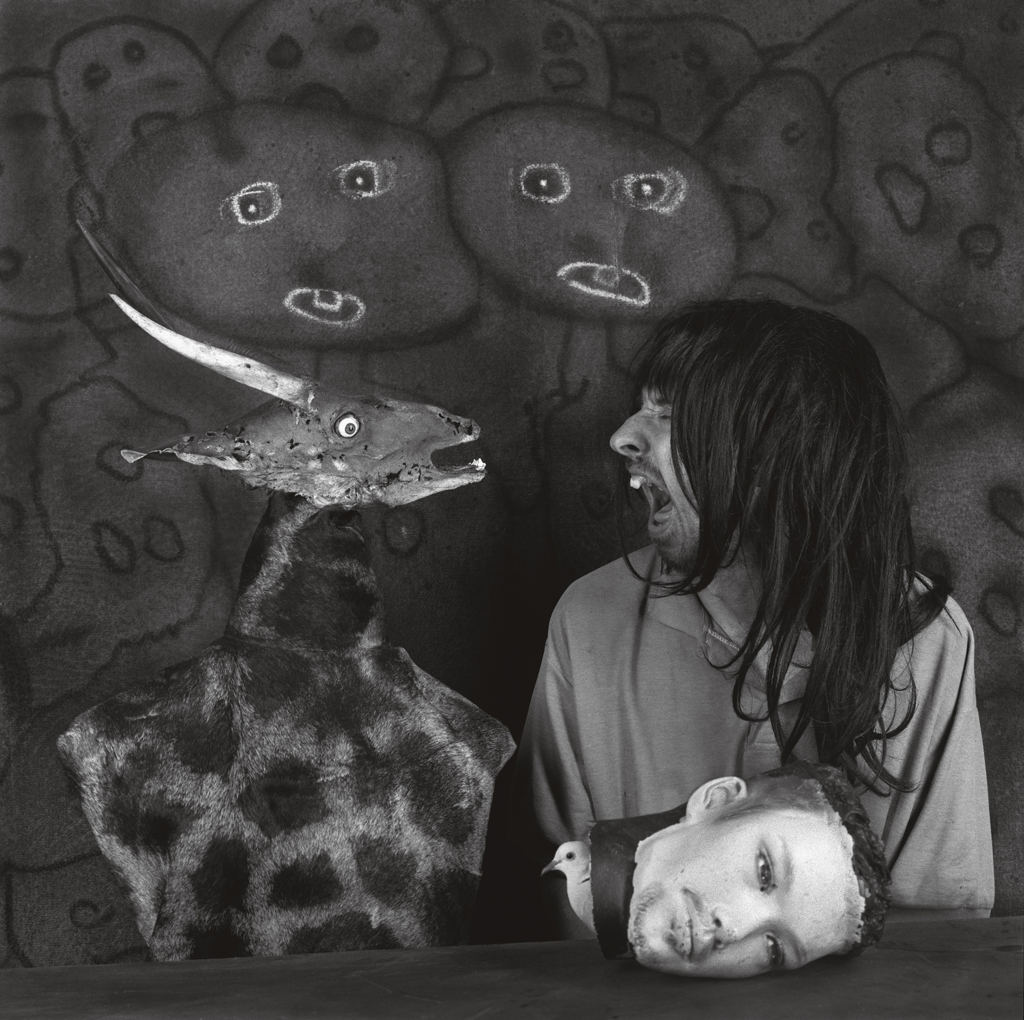

The strikingly Dante-esque views and symbolic narratives consistently portray an underground world, which can be construed as the mind itself.

At once grotesque, objective, sentimental, and sympathetic, the images his lenses capture are of outsiders, misfits, the diseased, and the mentally disabled, captured in asylums, caves, and in staged tableaus. Even his out-of-doors shots read as interiors. His series and books, which include Platteland, Outland, Shadow Chamber, Boarding House, Asylum of the Birds, and The Theatre of Apparitions (2016), have been appropriately assembled into this grand retrospective.

“My pictures,” he told me, “are not like anyone’s. They have nothing to do with any particular society; they have more to do with the human mind—the subconscious mind.”

Roger Ballen, Altercation, 2012.

©2017 ROGER BALLEN

Self-conscious, self-analytic, Ballen and the works can be viewed as one. This collection stands as the autobiography of Ballen’s life and art.

He grew up surrounded by photography, getting his first camera in the early ’60s, when he was 13. His mother had been working for Magnum in New York, where his family lived, and he became immersed in the work of the Magnum photographers, like Paul Strand, and captivated by some of his mother’s friends, like Andre Kertész, with his surrealistic images.

Ballen studied at the University of California, Berkeley during a period of artistic and political ferment. In 1972, his mother died. He then became obsessed with painting, studying at the Art Student’s League and making expressionistic Emil Nolde–like paintings. He writes of how that enabled him to plumb his psyche. “I remember a very erudite teacher commenting that my drawings ‘belonged in the Stone Age.’ ” In 1973, disaffected with the materialism of America, he took off for a five-year journey, beginning in Cape Town. And the rest is history—lots of it.

Animals and their relationships with humans have always played an important role in Ballen’s works. “The animals are living in an alienated, destructive space,” he said. “It’s always a challenge for humans to figure out what’s going on in an animal’s mind.”

“In the ’80s and ’90s, when I went into houses, people were drawing on walls,” he said, describing his relation to his South African subjects. “I liked the bird as a symbol of hope, but I found them locked up in these claustrophobic houses.” The walls were punctuated by twisted wires and objects hanging from cords, all adding up to a larger composition in which everything is linked, accidentally on purpose.

Roger Ballen, in collaboration with Hans Lemmen, Hug, 2016.

©2017 ROGER BALLEN

Ballen started taking pictures in these places in 2008: “I worked in that place where humans and animals interacted.” When he first started taking pictures, in the 1960s and 1970s, the message was not political or cultural, but rather, psychological. A geologist by profession, he explained that what he does, “metaphorically, is dig down deep in the psyche and concretize it.”

The ensuing images are filled with symbols as well as real animals, primitive drawings, and stray objects—but in some of his more recent works, Ballen has also been distancing himself from specific faces and people, including body parts instead, arguing that “the faces were prejudicing what I was trying to do. As long as there’s a face, humans will try to understand it.” His figures are much larger, and Ballen even includes deadpan photos of himself, but for the most part, instead of actual faces he has shifted to masks, dummies, cutouts, advertising models, and animal drawings. What faces there are, he said, are “all translated into the evolution of my aesthetic. I saw this created space as Ballen World.”

[ad_2]

Source link