Philip Guston’s KKK Paintings: Why an Abstract Painter Returned to Figuration to Confront Racism

In 1930, Philip Guston went to work on Conspirators, a tall painting featuring a trio of Ku Klux Klan members clustered in the midst of mysterious architectural elements. Their heads were bowed, and their hands brandished clubs and other weapons. Three years later, the painting went on view in Los Angeles at the Stanley Rose bookshop. But in a cruel twist of fate, people who had donned pointed hoods similar to the ones featured in the work ended up destroying Conspirators and various other works by Guston—with members of the Los Angeles Police Department, working with the Klan and the veterans’ organization the American Legion, shredding the works before the artist’s eyes.

Around the time of that fateful show, the KKK had taken hold in Orange County, with high-ranking civic officials joining the group to push racist, nativist ideologies in violent ways. Guston, a Jew whose people who were among those being targeted by the KKK, encountered the Klan’s activities there and grew horrified by what he saw. “He was not only a first-generation Jewish immigrant whose family had fled pogroms in Russia,” Musa Meyer, the artist’s daughter, told ARTnews, “but was in a larger sense committed to bearing witness and documenting injustice and inhumanity whenever it occurred.”

Guston worked in a number of artistic modes, from Renaissance-inspired figuration to formally accomplished abstraction. But no part of his oeuvre is as cryptic, strange, and difficult as his paintings and drawings of Klansmen. Their message is in certain ways clear, as Guston was affiliated very leftist groups early on in his career. (“This isn’t a guy who’s trying to promote the Klan,” Michael Auping, a curator who organized a Guston retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art Fort Worth in Texas, said recently.) But in their bracing acknowledgment of racism, they have had a tendency to provoke—as evidenced by the postponement last week of a Guston retrospective after the four museums presenting came to fear that audiences might not understand the full meaning of Guston’s KKK work.

Guston’s art of the 1930s shocked initially because it so baldly attacked its subject matter. Conspirators was created in the same style as a work made on commission for the Communist Party-affiliated John Reed Club, which asked Guston to respond to the state of the “American Negro.” The work he created focused on the Scottsboro Boys, nine Black teenagers who were falsely accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931. In one of Guston’s panels, a Klansman whips a nearly nude figure tied to a stake that looks like the Washington Monument. (That work was also destroyed in the Stanley Rose police raid.)

Philip Guston, Riding Around, 1969.

©The Estate of Philip Guston/Genevieve Hanson/Courtesy Hauser & Wirth/Private Collection

In a newly published monograph on Guston, curator Robert Storr writes, “In the ideologically polarized climate of that period—one that frighteningly anticipated the antagonism of the right-wing backlash in the United States culminating in the Trump era—the violence Guston allegorically portrayed in effect triggered an eruption of the real thing. This first trial by fire made it plain that although political art may not have the capacity to change the world, it can draw the evils that threaten society into the open, where they can be seen for what they are. It was a lesson the artist would not forget.”

Klansmen disappeared from Guston’s art for a while, after periods in which the artist variously took up tableaux inspired by Mexican muralism and abstractions similar to those of other artists active during the postwar era. But then they grandly returned nearly four decades later, in one of the artist’s most iconic bodies of work.

By then, Guston had been known as an acclaimed abstract painter. So it disappointed many when he returned to figuration with aplomb, painting mysterious images in which cartoonish-looking cups, heads, easels, and other visions were depicted against vacant beige backgrounds. “People whispered behind his back: He’s out of his mind, and this isn’t art,” Auping said. “He could have ruined his reputation, and some people said he did.”

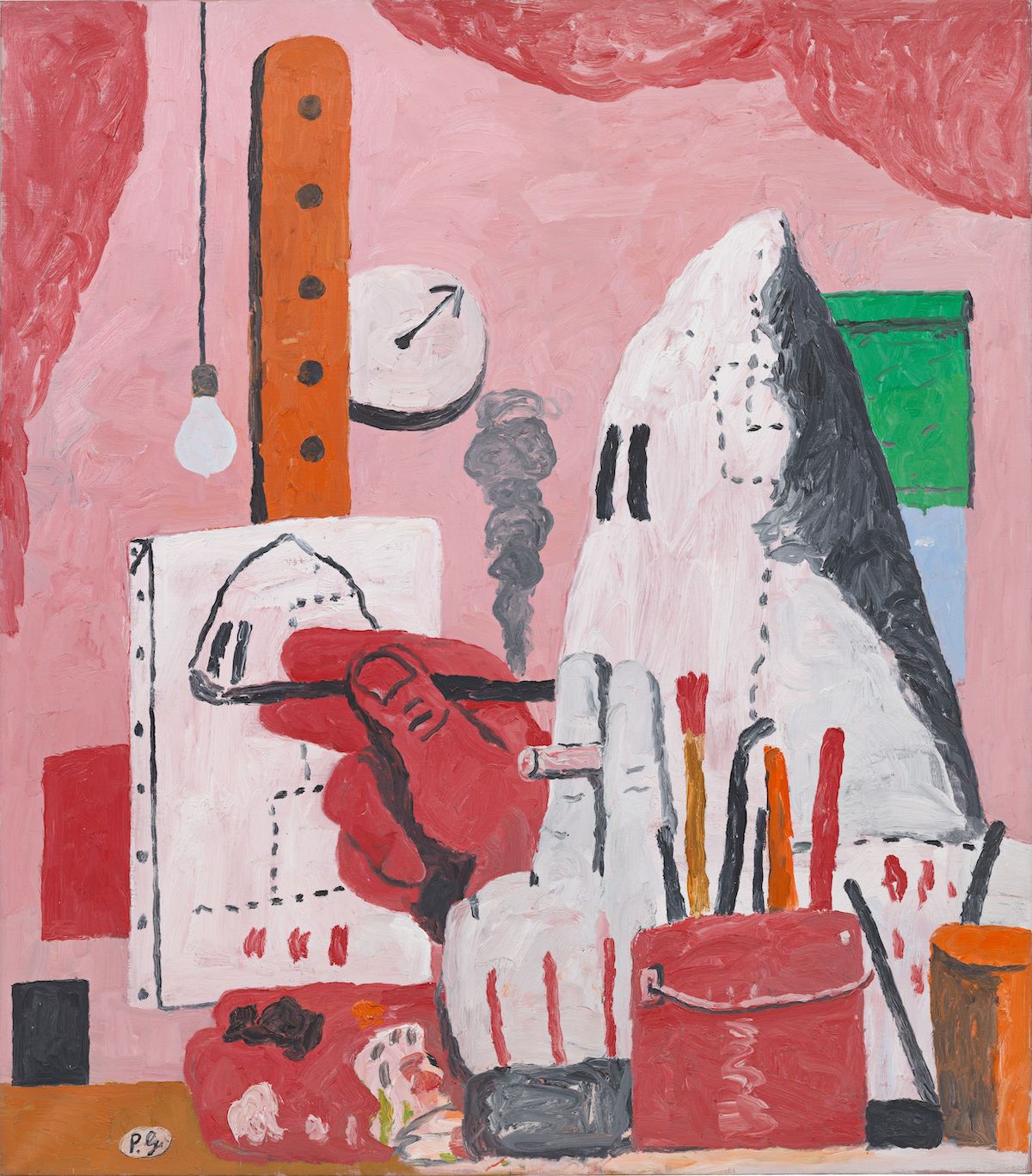

As his colleagues looked on in horror, Guston began pushing his figuration even further, with Klansmen back again in his canvases. In the 1930s works, his hooded figures were rendered with a level of realism, their robes intricately rendered with chiaroscuro lighting. Starting in 1968, however, they were rendered with a kind of jokiness, their pointed hoods appearing poorly sewn and droopy. They often have big red mitts for hands, and they often converse while puffing on cigarettes and riding packed in cars like clowns. In a few cases, his Klansmen are shown creating artworks.

Philip Guston, The Studio, 1969.

©The Estate of Philip Guston/Genevieve Hanson/Courtesy Hauser & Wirth/Private Collection

Made in response to various instances of social upheaval in the U.S.—including the showdown between protesters and the police at the Democratic National Convention and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., both in 1968—Guston’s works do not shy away from violence. One titled Bad Times (1970) features two Klansmen riding in a car, with one pointing a handgun at a figure who seems to have been shot dead, his oversized feet sticking out from behind an urban edifice. “They were exciting because they reflected so much of what was happening in the world at that time in America, the civil rights disturbances and the marches and the fires and the anger and the disruption of everything,” dealer David McKee said, according to a text reprinted on the Philip Guston Foundation’s website. “And we would talk about his own early interests in taking a position against social injustice.”

Guston’s Klan works of the late ’60s and early ’70s nag at the minds of many viewers because they are hard to parse. Where are these jalopy-riding Klansmen going—to kill someone, to attend a meeting, to do something altogether more commonplace like visit a store or a bar? Why do some of the Klansmen appear to be sad? Why are their hands so big? And what’s with the giant maroon fingers that are sometimes shown pointing at them? Also, how can a Klansmen whose hood has no mouth-opening smoke a cigarette, anyway?

Guston chose to leave these sorts of questions open, though he sometimes described the works as “self-portraits,” alluding to the fact that he was trying to understand the racist ideologies that guided these people—which, he believed, may also exist inside him in some way. Asked to characterize Guston’s thinking, Auping imagined the artist saying, “The only way I can understand outside evil is if there is evil inside of me.”

Philip Guston, Blackboard, 1969.

©The Estate of Philip Guston/Genevieve Hanson/Courtesy Hauser & Wirth/Private Collection

Others have suggested complex autobiographical meanings for the works. For decades early in his life, Guston’s last name was Goldstein—before he renounced it in an attempt to mask his Jewish identity. During the 1960s, however, he led a quest to reconnect with his Jewish heritage. Could the hooded figures some allude to the way he cloaked his own identity, keeping it out of view of the public? Art historian Donald Kuspit claimed as much when he wrote that the hood “signals his sense of being ‘faceless,’ that is, without an artistic identity. Is he also hiding, in shame, a so-called ‘Jewish face?’”

Whatever rich metaphorical content can be wrung from the paintings now, the works were thought to be duds when they debuted in 1970 at Marlborough Gallery in New York, which gave Guston the slot in its fall season with the greatest visibility. Critics lambasted the show—and alleged that the KKK works represented a poor attempt by Guston to stay relevant. In one famous review printed in Time magazine, Robert Hughes said it may have been “a little late in the century to mount an entire exhibition on the Ku Klux Klan.” In another printed in the New York Times, Hilton Kramer, a critic with aesthetically and politically conservative inclinations, gave Guston the harshest review of his career, calling the Klansmen paintings the “artistic equivalent of a ‘pseudoevent.’”

Since then, many artists have defended the Klan works. In the catalogue for the newly postponed Guston retrospective, Glenn Ligon writes, “Guston’s ‘hood’ paintings, with their ambiguous narratives and incendiary subject matter, are not asleep—they’re woke.” And in an essay for the same book, Trenton Doyle Hancock writes that “Guston describes something beyond the occasion, something lurking under the white hoods”—racism writ large.

Musa Mayer, the artist’s daughter, explained the paintings’ enduring power by quoting a New Yorker review of the Marlborough show by Harold Rosenberg: “Today, it would not be accurate to say that by picturing the banality of daily Klan life, ‘the personification of violence and tyranny puts politics at a distance.’”

Published at Wed, 30 Sep 2020 14:02:01 +0000