[ad_1]

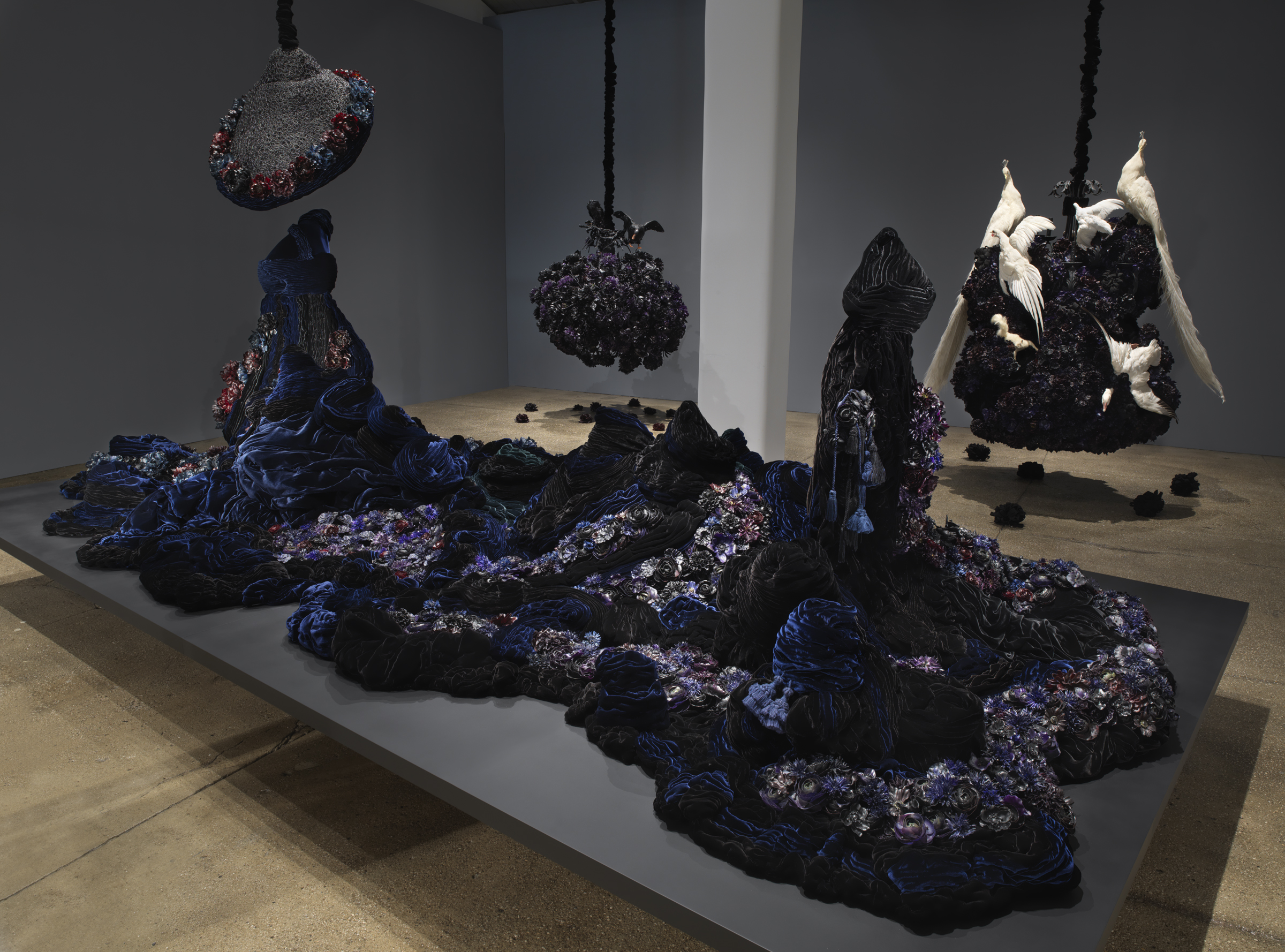

Installation view of “Petah Coyne: Having Gone I Will Return” at Galerie Lelong, New York. Coyne’s Untitled #1379 (The Doctor’s Wife), 1997–2018, is in the foreground, and Untitled #1375 (No Reason Except Love: Portrait of a Marriage), 2011–12, is at right.

COURTESY GALERIE LELONG

One balmy afternoon this summer, the artist Petah Coyne was standing inside her sprawling studio in West New York, across the Hudson River in New Jersey, surveying some of her recent sculptures. “It’s like characters when you write—they start doing their own thing,” she said excitedly, of the works. “You just have to go with them.”

They have taken her to some wild places. Assembled in a serene, crepuscular solo show at Galerie Lelong & Co. in Manhattan, her first in the city in nearly 10 years, they are classic Coyne, conveying cryptic narratives via unrepentant decadence—lush fabric, dripping wax, and immaculate taxidermy, often assembled in intricate goth chandeliers—but they also feel uniquely intense in their psychological acuity. They smolder with darkness.

Walking from one work to the next, sometimes accompanied by assistants, Coyne, 65, was animated and charmingly wry, even when recalling the harrowing efforts that went into a given piece. “This is what we have been sewing for a year and a half, and we are so glad that we are finished!” she announced as she examined Untitled #1379 (The Doctor’s Wife), 1997–2018, a mountainous world, more than 16 feet long, of silk flowers and flows of velvet, punctuated by two mysterious hooded figures who seem to be in silent conflict, brooding. (Like many pieces in the show, it’s inspired by Japanese literature, in this case Sawako Ariyoshi’s eponymous 1966 novel.)

An installation view of Coyne’s smoldering Lelong show, with Untitled #1242 (Black Snowflake), 2007–12, at front, and Untitled #1177M (Tamura Toshiko), 2003–18, behind it to the right.

COURTESY GALERIE LELONG

At Lelong, The Doctor’s Wife is the exhibition’s pièce de résistance, and viewers can take it in from a raised viewing platform; in Coyne’s studio, I climbed atop a ladder to see it all, as she detailed the trial-and-error method she used to create the piece. “I tried to do just fabric, and it was way too heavy,” she said. “I tried to do flowers and hair. I tried all these different materials that I have at hand and nothing worked. It looked awful. Just awful. I was so depressed. It just was too heavy. So I ripped it all apart.” Finally, “just a little bit of the flowers with velvet looked really good.”

Coyne is a perfectionist, more than willing to tear up untold amounts of labor and start anew. “People who work for me have to be able to accept change,” she said. “Some of them can’t, and they don’t stay long. They get very upset.”

Her creations are fantastical—extreme Rococo, the stuff of sci-fi nobility—but they are also personal, and sometimes mournful. Untitled #1375 (No Reason Except Love: Portrait of a Marriage), 2011–12, was informed by her longtime friend, the poet Leslie Scalapino, who died in 2010, and her husband, Tom White. Two albino peacocks are perched atop a huge, hanging mound of silk flowers—deep purples, burgundies, blacks—while still more alabaster-colored birds seem to fly through and around it, a vision of radiant energy momentarily stilled. Explaining the color of her avian inclusions, Coyne recalled a conversation with White: “He said that all of the color had just gone out of his life when she died.”

Lying on the ground and peering up into the interior of the hanging piece, I saw thin rays of light streaming through its layers of petals and metal wiring. “It kind of looks like the birth canal a wee bit,” Coyne suggested.

Coyne was born in Oklahoma City and, as a result of her father working with the military, moved constantly throughout her childhood. “Whenever we were on the road and traveling, wherever we stopped, we first went to the church and thanked God that we arrived OK,” she said. “And when we were traveling, we always said the rosary.”

Though she is not a churchgoer today, the sumptuousness of so many Catholic cathedrals imbues her work, and the material lists for her sculptures reads like a shopping list for an especially worldly cardinal with an interest in BDSM. Portrait of a Marriage includes “silk flowers, taxidermy, chandelier, candles, ribbons, black sand from pig iron casting, resin, paint, black pearl-headed hat pins, chicken-wire fencing, wire, cable, cable nuts, quick-link shackles, jaw-to-jaw swivel, silk/rayon velvet, ⅜″ Grade 30 proof coil chain, Velcro,” plus “specially-formulated wax,” a pricey archival material that she developed with a chemist friend and patented. “It’s scalding hot—220, 240 degrees,” she said. “You just throw it and get out of the way.”

An installation view of the Lelong exhibition, with Coyne’s Untitled #1388 (The Unconsoled), 2013–14, at back.

COURTESY GALERIE LELONG

Walking through her studio, we also passed about a dozen stuffed peacocks, purchased from a farm in Upstate New York, which will one day find their way into her sculptures. In graveyards in Ireland, “they have lots of peacocks, because they believe the peacocks take the souls to heaven,” Coyne said, merrily. “Did you know that?” (I did not.) “That’s why they let them run free in the graveyard. I love that.”

Elsewhere, assistants were dabbing what looked like fine black salt onto Untitled #1177M (Tamura Toshiko), 2003–18, a chandelier resembling a Jeff Koons “Hanging Heart” sculpture that has sprouted craggy capillaries or barbed wire. It could be a depiction of the Sacred Heart of Jesus or something evil—very potent, either way. Coyne handed me a pail of the black sand—the leftover material from pig iron casting—and I let it run through my fingers. “Isn’t that the most sensuous, beautiful thing?” she asked. “It’s like a black sand beach in Hawaii.”

The opening of the Lelong show, which runs through October 27, was a few weeks off, and soon art handlers would be arriving to pick up works, which are not simple to move. Some weigh hundreds of pounds, and then there’s the matter of their immensely action-packed surfaces. “The outside is the most delicate, and then it gets tougher and tougher and tougher inside,” Coyne told me at one point. “So, you know, I always connote them to women—we’ll cry on the surface, but don’t mess with us. Tough as nails. It’s kind of like the velvet hammer, right? I think that’s how females are a lot of times.”

[ad_2]

Source link