[ad_1]

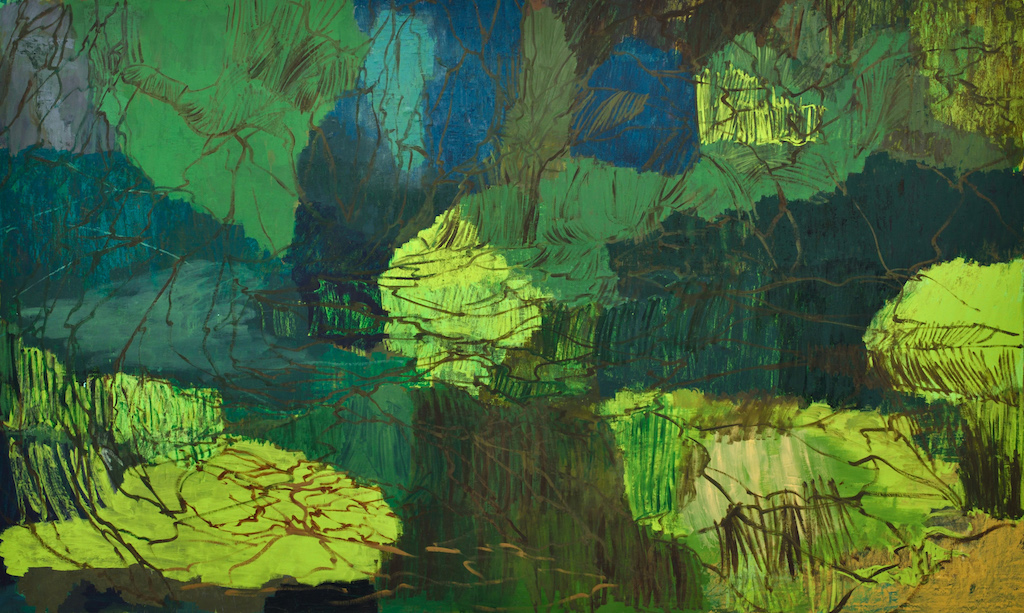

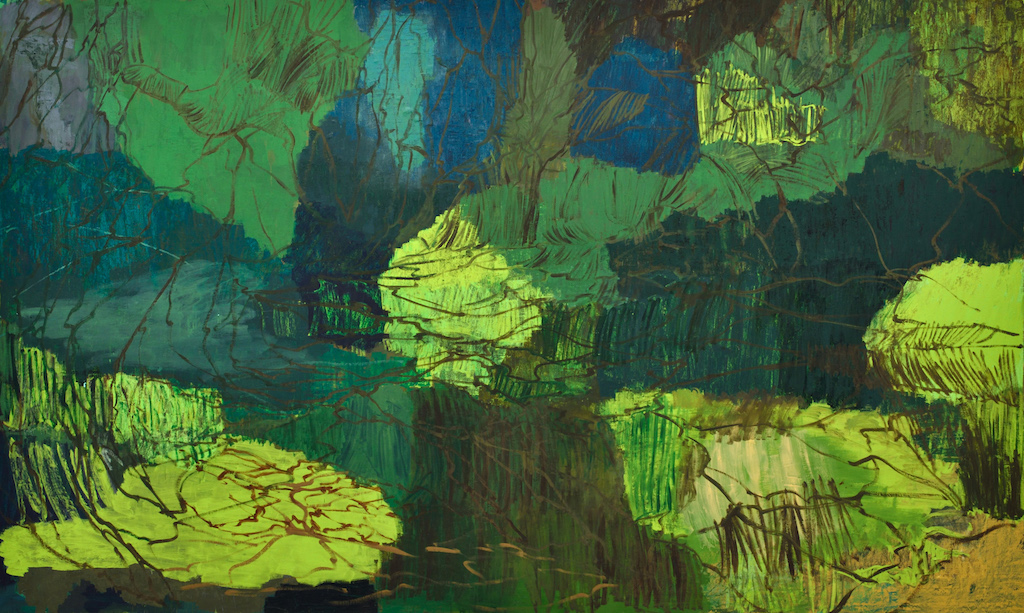

Per Kirkeby, Untitled, 1999, oil on canvas.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND MICHAEL WERNER, NEW YORK AND LONDON

In 1997, Paul Levine, then a Copenhagen correspondent for ARTnews, visited Per Kirkeby’s studio for a profile in the magazine. Levine asked Kirkeby about the inward-looking nature of his canvases, which tended toward the dark and brooding, often earthy tones piled on top of one another. “In my paintings, you experience a clear sense of space, and at the same time you also feel enclosed,” Kirkeby said. In other words, his canvases were not open expanses of color similar to those favored by the Abstract Expressionists in the 1940s. Kirkeby was also wry enough to add, “You want to enter into that space, and you end up knocking your head against the wall. I cannot explain that. I don’t know why that is.”

That sense of ambition tempered by a sense of dry wit carried through much of the work of Kirkeby, who died today at the age of 79. The passing of one of the leading painters of the Neo-Expressionist movement was announced by his longtime gallery, Michael Werner, which has spaces in New York, London, and Märkisch Wilmensdorf, Germany.

Kirkeby rose to notoriety during the early 1980s alongside fellow European Neo-Expressionist artists Markus Lüpertz, A. R. Penck, Jörg Immendorff, and Georg Baselitz, all of whom brought a renewed emphasis on formalism and painterly technique to an art world that had, by then, nearly given up on their medium. Unlike his colleagues, who were mainly active in Germany, Kirkeby was born in Denmark and was, at certain points in his career, based in Copenhagen. He often ascribed a Nordic sensibility to his work, noting that, in comparison to the monumental paintings produced by Baselitz and Lüpertz, his canvases alluded frequently to geological formations and landscapes, as opposed to people and emotional states.

Per Kirkeby, The Siege of Constantinople, 1995, oil on canvas.

COURTESY TATE, LONDON

Almost immediately, the Neo-Expressionists, Kirkeby among them, began receiving critical attention, both good and bad. In a New York Times review under the headline “A Big Berlin Show Misses the Mark,” John Russell dismissed the title of a 1982 survey exhibition, “Zeitgeist,” as “presumptuous.” Other critics took Neo-Expressionism to task for reviving the masculinist tropes that had been wielded by many Abstract Expressionist painters, often at the expense of their movement’s female members.

Kirkeby’s work came under scrutiny of its own. Peter Schjeldahl once wrote that the relationship between figure and ground in Kirkeby’s canvases was “as haphazard as a pile of laundry.” But there were more positive notices, too. In 1981, the Welsh art critic Stuart Morgan wrote in Artforum, “Kirkeby is that art-historical rarity, the artist who revives a defunct movement and kills it off again almost immediately.”

Kirkeby himself often spoke about his work in opposition to the techniques first made famous by the Action Painters. While his process likewise involved the intense layering of paint, frequently applying and reapplying strokes, some of them brushy, some of them thick, Kirkeby thought of his practice as softer than theirs, as well as that of the German Neo-Expressionists. In Scandinavia, he believed, artists prioritized color over form, while in Germany and the United States, the opposite was true. But he also knew that his work would be nothing without that of Jackson Pollock and others, and once noted, “We in Europe have always known that everything has already been done before.”

Per Kirkeby, Inferno IV, 1992, oil on canvas.

COURTESY MICHAEL WERNER GALLERY, NEW YORK AND LONDON

Much of Kirkeby’s international exposure came by way of his gallery, Michael Werner, which has worked with the artist since 1974. Kirkeby once described being willfully naive about Werner’s first visit to his studio. Werner’s gallery had established itself as an important force in the German art world, having shown Penck, Kiefer, Baselitz, and Immendorff early on, but Kirkeby claimed he had never even heard of him or many of the artists on his roster. After the studio visit, Kirkeby was skeptical of the dealer but eventually agreed to a one-man show. The relationship stuck.

“Per was an extraordinary man and an incredibly important and vital figure in painting,” Gordon VeneKlasen, a partner and co-owner of Michael Werner Gallery, told ARTnews. “He was widely respected and adored—as both a teacher and an artist. He was one of the first artists to join the gallery and had a close personal and professional relationship with Michael Werner for nearly 45 years. Per and I also shared a close relationship, traveling around the U.S., South America, and Europe together for nearly three decades. It’s a real personal loss—he will be dearly missed.”

Kirkeby’s work subsequently began showing up at major exhibitions around the world, notably the painting-heavy 1982 edition of Documenta, curated by Rudi Fuchs. His work also appeared at the 1992 edition of the quinquennial, as well as at the 1976, 1980, 1993, and 1997 editions of the Venice Biennale. In 2008, his work was the subject of a retrospective that began at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humblebaek, Denmark, and traveled to Tate Modern in London and the Museum Kunst Palast in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Per Kirkeby, Untitled, 2005, tempera on canvas.

COURTESY MICHAEL WERNER GALLERY, NEW YORK AND LONDON

Kirkeby was born in 1938 in Copenhagen, in a working-class neighborhood known for its church, which went on to inspire some of the artist’s early creations. From a young age, he knew that he wanted to be a painter. In his ARTnews profile, he described how, for one assignment in school, an art teacher asked him to draw a flower—but after his version proved generic and idealized, made entirely from memory and bearing no resemblance to the flower in front of him, he decided he couldn’t make a living as an artist and went on to study geology at Copenhagen University.

Nature continued to be of prime importance to Kirkeby, even as he took a more experimental route once he went back to school, this time an art school in the Danish capital. Some of his first works were Fluxus- and Minimalism-inspired pieces that drew on Marxist philosophy and contemporary politics. Even though these works, which sometimes took the form of structures made of bricks, may not resemble his paintings, they foreshadowed an interest in the formal properties of space and ways one can inhabit an environment.

Drawing on the history of Nordic art, in particular Edvard Munch’s moody tableaux, Kirkeby engineered a style that placed an emphasis on mossy greens and dirt-like browns, sometimes punctuated by bursts of fiery red and orange. These hues were not necessarily foreboding in his hands, however. “My canvas is the plot of land and my colors—that is, the matter of paint itself—are the soil, the flower beds, with their different components and varying textures,” he said. “This may be a quaint way of speaking; yet, in practice, it is exactly how I work.”

[ad_2]

Source link