[ad_1]

Installation view of “Projects 195: Park McArthur,” October 27, 2018–January 27, 2019, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/DIGITAL IMAGE © 2018 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/PHOTO BY DENIS DOORLY

In this ART OF THE CITY column: PARK MCARTHUR offers an elegant critique of MoMA’s big-budget expansion (and philanthropy writ large), HEATHER GUERTIN serves up a fresh batch of paintings at Brennan & Griffin, and the newly relocated RAMIKEN CRUCIBLE comes out swinging.

1. RIP IT UP AND START AGAIN

Offered the chance to have an exhibition in a prime space at the Museum of Modern Art in New York—an opportunity that any early-career artist would kill for—Park McArthur has responded by leaving it nearly empty.

The title of the New Yorker’s show, “Projects 195: Park McArthur,” appears in huge letters wrapped around two walls of a capacious fourth-floor gallery that overlooks the museum’s sculpture garden. There are also two leather couches and two frames hanging on the wall that hold promotional papers for 53W53, the 82-story Jean Nouvel–designed luxury condo tower that will house part of MoMA’s forthcoming $400 million expansion. Those papers list some of the “impeccably detailed residences” available—a $3.65 million one-bedroom and a $42.5 million four-bedroom—and note that 53W53 sports amenities like a pet concierge, “poolside vertical hydroponic gardens,” and emergency generator support.

Through her exhibition, McArthur is proposing a very different kind of structure. In an accompanying audio guide, which is the heart of this incisive artist’s project, a museum educator named Paula Stuttman intones, “Now I invite you to imagine a building. This building does not exist. At present it lives in the mind of the artist as a persistent daydream.” It has studios, a ramped indoor pool, and accessible common spaces where “you overhear conversations and laughter.” Income is “not the determining factor for living here.”

Installation view of “Projects 195: Park McArthur,” October 27, 2018–January 27, 2019, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/DIGITAL IMAGE © 2018 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/PHOTO BY DENIS DOORLY

A metal model of a building that looks a bit like part of MoMA sits, partially hidden, in an alcove off the almost-vacant gallery. Miniature versions of the room you’re standing in—one with a ramped pools—are arrayed on the floor behind it, like architectural proposals awaiting customization and funding. Throughout the exhibition’s run (through January 27, 2019), they will be reconfigured.

The audio component of the show, which is available online, is titled PARA-SITES (2018), and in her bracingly spare installation, which was curated by MoMA’s Magnus Schaefer with Tara Keny, McArthur is asking of the big-ticket construction work that is underway: Who is feeding off of whom here? And, more broadly, what tradeoffs—in terms of money, power, and physical space—do our arts institutions facilitate? Right now, some 150 homes for the very wealthy are being readied high in the sky, and about 50,000 square feet of exhibition space is being added to MoMA. The audio points also out the letters on the wall denoting the David Geffen Galleries, named in honor of that entertainment magnate’s $100 million donation to MoMA in 2016.

Meanwhile, homelessness in New York is the highest it has been since the 1930s, and about one in ten children in the city’s public schools sleeps in temporary housing. Not far from MoMA, work continues on a public sculpture—Thomas Heatherwick’s ridiculous Vessel—that has cost more than $150 million to build.

With impressive concision, McArthur is underscoring the capriciousness and cruelty in how philanthropy and real estate operate today. Is she having her cake and eating it, too, sharing fanciful and politically loaded plans from within the comfort of the institution? Sure. But she’s doing what she can: spotlighting a problem and offering one possible alternative. Others will need to act. “Now I invite you to imagine a building,” her piece says. “This building does not exist.” Not yet.

Installation view of “Heather Guertin: Two Thousand Eighteen” at Brennan & Griffin, New York.

COURTESY BRENNAN & GRIFFIN

2. IN MOTION

No show of fresh new paintings this season has dazzled me quite like Heather Guertin’s third solo outing at Brennan & Griffin (through November 25). These are bright, glowing abstractions, made with quick strokes (most bold, a few faltering) that seem all the faster because they flow around three or four monochromatic circles that anchor each canvas. Guertin, who’s based in New York, is using a lot of color very masterfully, and a few works suggest Hans Hofmann in his most radiant pitch but loosening things up unexpectedly, letting in a bit more chaos. Peculiar as it sounds, the off-kilter charm of Guertin’s compositions also brings to mind Allan Kaprow’s early free-form figurative efforts. But this is no nostalgia cruise. At once a tasty artisanal surface and redolent of a digital screen (which is to say: humming with discrete activities), each Guertin feels momentarily stilled. Pretty soon, those circles could become heads on bodies, perhaps, or moons rising above an alien planet. For just this moment, they’re with us. What happens next is anyone’s guess.

3. WELCOME BACK, CRUCIBLE

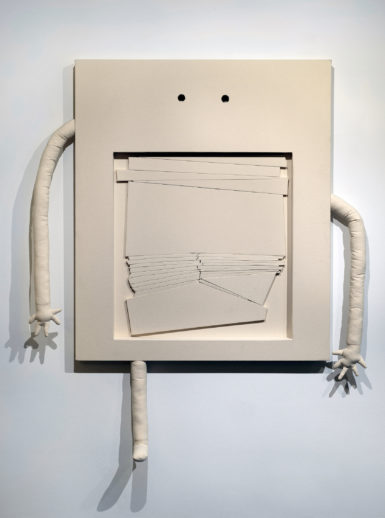

Wyatt Kahn, Him and Sam, 2018.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND RAMIKEN CRUCIBLE

It’s been a bit sad in New York’s gallery scene of late, with stalwarts like Real Fine Arts, Cleopatra’s, and Signal closing, so it’s a thrill to be able finally to deliver some good news. After a yearlong sojourn in Los Angeles, the reliably unpredictable Ramiken Crucible has returned to New York and opened an invigorating group show called “Hardcore Erotic Art.” (True to Ramiken’s typical cloak-and-dagger practices, the location of the show, which is up through December 15, is private: reach out directly.) A good slice of the familiar gang is here, including Andra Ursuta, with a slice of the penis-bedecked rock-climbing wall she showed in 2016 at the New Museum; Elaine Cameron-Weir, presenting a metal and patent-leather chair that is straight out of a vintage sci-fi horror film; Wyatt Kahn, offering a new version of his lovable (and a little unsettling) anthropomorphic canvases; and Eli Ping, whose off-white, nearly 11-foot-tall resin-soaked fabric piece dominates one wall, looking like a sensual Robert Morris felt work slipping in from another dimension. It is a forward-looking exercise in how the body can be toyed with (or tortured) in ways that are uproarious, creepy, and abject—exactly the sort of thing we have come to expect from Ramiken. Intriguingly, though, there are also a few curveballs, like a little Tony Smith maquette, a resplendent Eva LeWitt, and a small drawing by Jacques Villon (one of Marcel Duchamp’s older brothers) of dice tumbling through the air, which I will take in this context as a tribute to artists and dealers that are willing to take chances.

[ad_2]

Source link