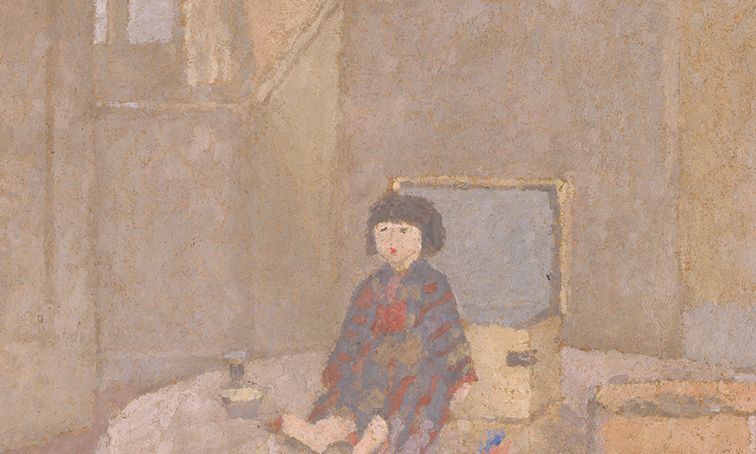

Gwen John‘s Japanese Doll (1920) will be displayed alongside works by other artists such as Pierre Bonnard and Spencer Gore in the exhibition

© National Museum of Wales

“I think Gwen John has been pushed out to the peripheries because of the way she was understood,” says Alicia Foster, the curator of Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. The exhibition will feature paintings, watercolours and drawings spanning John’s career, from her time at London’s Slade School of Fine Art and relocation to Paris, to works produced in Meudon, where she spent the last years of her life. The show promises to challenge John’s reputation “as a recluse, cut off from the life and art” of her times, Foster says, a reputation that has significantly “diminished the resonance of her work”.

Featuring more than 120 works, the exhibition will chart John’s development from the 1890s—represented by the early, Munch-like painting Landscape at Tenby with Figures (around 1896-97)—to her muted, timeless portraits of young women and girls. Rare watercolours and sketches will offer new insight into the sureness of John’s drawing, while the exhibition will close with a series of late landscapes, revealing her sustained engagements with the ongoing developments of Modernism. Three versions of her quiet masterpiece The Convalescent (1918-24) will also be reunited.

Since her death in 1939, John’s significance has often been reduced to her association with her brother, Augustus, or to the sculptor Auguste Rodin, for whom she modelled in Paris during their ten-year affair. While Foster’s exhibition reclaims for John some independence, it does so by widening the scope of her artistic exchange, positioning her among a range of European contemporaries, from the poet Rainer Maria Rilke to the diverse painters with whom the exhibition pairs her work, such as Édouard Vuillard, James McNeill Whistler and Walter Sickert. John’s paintings will be brought into focus, too, through juxtaposition with several female contemporaries, particularly Mary Constance Lloyd and Ursula Tyrwhitt, while her hazy, tonal studies of domestic interiors—like A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris (around 1907-09)—appear alongside Pierre Bonnard and Spencer Gore.

Foster hopes to reilluminate John’s art with the exhibition as well as with a new biography, examining not only “what it meant in her own time”, she says, but “what it might give to ours”.