[ad_1]

How much time does it take to sell an artwork at an art fair, never mind 10 of them? According to one gallery, zero minutes and zero seconds.

At 2 p.m. on Wednesday, precisely as Art Basel Hong Kong opened its doors to its first VIP guests, a publicist for Los Angeles’s David Kordansky Gallery sent an email to press announcing some “exciting sales updates on behalf of David Kordansky Gallery for the first day of Art Basel Hong Kong.” The first day literally hadn’t begun and, according to the email, Kordansky’s sales included a parabolic lens by Fred Eversley for $250,000, a Rashid Johnson for $210,000, a Jonas Wood for $175,000, a Matthew Brannon for $48,000, another Jonas Wood for $120,000, a Calvin Marcus for $38,000, an Ivan Morley for $36,000, a Will Boone for $35,000, and a Lauren Halsey for $30,000. (All prices are in U.S. dollars, unless noted.)

How could it be?

The crowd this year at Art Basel Hong Kong was “instantaneous,” Kordansky’s Kurt Mueller told ARTnews, and “the energy very, very high.”

“We were prepared,” Mueller explained. “There were some things on hold that we’ve confirmed.”

It raises the old question, well known to market journalists, of what exactly counts as a sale made at a fair. Galleries send out previews to clients. Does a confirmation from a potential buyer who might not even be at the fair count as a sale made at the fair? As Bill Clinton might put it, it depends on what the meaning of the word “at” is . . .

This is the seventh edition of Art Basel Hong Kong, a fair that began under different ownership (and a different name) in 2008. This year brings 242 galleries from 35 countries to the show, which runs through Sunday. At day’s end—arguably a more reasonable time to determine what sold at a fair—Art Basel reported that sales included a significant work by Andy Warhol at White Cube for $2.85 million and a painting by George Condo at Almine Rech Gallery for a price in the range of $1.2 million to $1.4 million. David Zwirner sold its entire booth on the first VIP day, including four new sculptures by Carol Bove for $400,000 to $500,000 each.

Perhaps the best indication of this fair’s evolution is that Paris- and Salzburg-based dealer Thaddaeus Ropac can now bring Warhol’s 30 Colored Maos (Reversal Series), 1980, and not seem to be pandering to a cliched conception of regional taste. Whereas, back in 2010, every other gallery from the West seemed to have a Warhol Mao, or a grab-bag of flashy eye-candy works, Ropac’s Maos looked like an organic addition to his presentation of work from the late 1970s and early ’80s, by artists like Georg Baselitz and Sigmar Polke.

“We did think about it,” Ropac said, discussing his decision to include the piece. “We hesitated. We did bring a Mao to the fair many years ago. But now it’s understood in a different context. The quality of this fair is now on par with the great European fairs. It is highly sophisticated.”

There’s an interesting backstory to 30 Colored Maos, which is priced at $8.75 million. Commissioned by Warhol’s Swiss dealer, Bruno Bischofberger, for an exhibition at his Zurich gallery in 1980, the piece was on display not much later in Daniel Templon’s gallery in Paris, and was stolen. In June 2007, it turned up again at Sotheby’s London, consigned by the Art Loss Register on behalf of insurers, where it sold for £1.25 million. (A Sotheby’s specialist contacted ALR after noticing gaps in the painting’s provenance when it was brought in.)

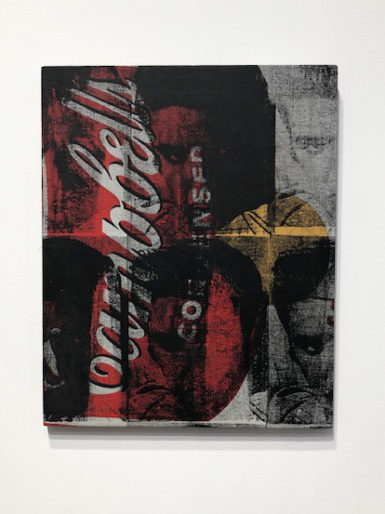

Also in the category of Warhols with interesting backstories would be Campbell’s Elvis (1962), the piece that sold at White Cube for $2.85 million. A merger of Warhol’s Campbell’s soup can and Elvis themes, the small silkscreen on canvas has a who’s-who provenance: former owners include Surrealist Salvador Dalí, casino magnate Steve Wynn, and longtime Gagosian Los Angeles director and eagle-eyed collector Bob Shapazian. When Shapazian’s terrific collection went up for sale at Christie’s in 2010, after his death, none other than White Cube founder Jay Jopling picked up the painting for $1.5 million.

Warhol being a mainstay of most high-end fairs, there were other pieces by him on offer. Acquavella has Five Deaths on Turquoise, from 1963, a 30-by-30-inch scene of a crashed, overturned car, priced at $15 million. The picture went for $9.8 million at Christie’s in May 2015; it made $7.3 million at Sotheby’s New York in November 2013.

And Gagosian has Warhol flowers from 1964 for $7.5 million. A fun fact about Gagosian’s just-opened exhibition “Cézanne, Morandi, and Sanyu” at the gallery’s Pedder Building space, curated by Chinese artist Zeng Fanzhi: not one piece is for sale. The artist wanted “no commercial overtones,” Gagosian director Andrew Fabricant told ARTnews.

For a well-capitalized gallery like Gagosian, such exhibitions are a way of flexing muscle in a relatively new market—and getting loans that prove you can go head-to-head with the auction houses. If you dropped by, you might have noticed the gallery has Cézanne’s Arbres et maisons au bord de l’eau (1892–93), a stunning landscape that sold in November at Sotheby’s New York for $11.1 million that had been in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Speaking of flexing muscle, Gagosian is vying for the most-photographed artwork in the fair with Duane Hanson’s Flea Market Lady (1990). Facing the aisle, the hyper-realistic life-size bronze sculpture is of a paunchy late-middle-age woman in a yellow visor and a baby blue Florida T-shirt hawking her wares (including shoes and clothing and a straw hat), not unlike a dealer at an art fair. Gagosian has it on offer for $750,000, but you may remember seeing it at New York’s Independent fair in November 2014, presented by the art and bookseller Karma, which priced it, back then, at $400,000. Maybe in all its trashy brilliance it might remind one, in the Hong Kong context, of U.S.–China trade relations?

“It seemed appropriate for an art fair,” Karma proprietor Brendan Dugan told ARTnews of the work back in 2014. “Duane lived in Florida, and Florida is definitely a place where you see a lot of America.”

As Enid Tsui observed in the South China Morning Post today, this year’s Art Basel Hong Kong is not defined by huge-ticket pieces. There is no $35 million de Kooning, as there was at Lévy Gorvy’s booth last year. This time around, Tsui writes, “prices around the $50,000 mark [are] less rare than before, a reflection perhaps of sentiment about the global economy.”

Among the bigger-ticket artworks, though, are some Picassos. Almine Rech, for instance, is displaying the painter’s striking Femme assise de la robe verte (1961), priced at $11 million. As it happens, Mainland China’s biggest-ever presentation of Picasso’s work is coming up—opening June 15 at the UCCA in Beijing is the not-so-subtly titled “Birth of a Genius,” comprising 103 works, no fewer than 30 of them paintings, from the Musée Picasso in Paris.

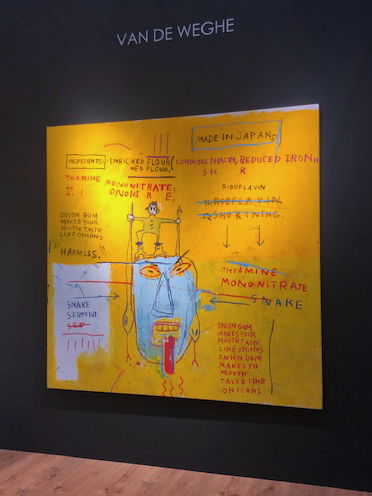

And what fair these days would be complete without a handful of Basquiats? Acquavella has two, including the bright yellow Untitled (Venus 2000 B.C.) from 1982 (the year of the $110.5 million painting sold at auction two years ago to Yusaku Maezawa), priced at $6 million. The painting was at auction at Phillips New York in May 2017, where it sold for $2.6 million.

Around the corner from Acquavella, Van de Weghe has Ape (1984) priced at $4 million (a reappearance from its booth at Art Basel in Miami in December) and another Basquiat, the large and bright yellow Onion Gum (1983) at $18 million. (Which is something of a price jump: the work sold at Sotheby’s New York in November 2012 for $7.4 million, then came up again at the same house in May 2016 and made $6.6 million.)

Pace Gallery, which has operated a location in Beijing since 2008, in addition to spaces in New York, London, Geneva, Seoul, Hong Kong, and Palo Alto, sold two-thirds of its booth on opening day, including a large painting from 2012 by Zhang Xiaogang, which went to a Chinese foundation for $1 million.

“While the focus is to increase our artists’ presence in Asia, the work that’s being shown and the collectors who are attending are far more global and integrated than ever before,” said Pace VP Adam Sheffer, who had previously done the fair with Cheim & Read, where he was a partner before joining Pace. It is no longer the situation, he said, that this is a fair galleries “write off. It is now where you make a profit.”

Mainland Chinese collectors were on hand, such as Li Lin, Yang Bin, and Qiao Zhibing, who just opened his Tanks project in Shanghai—a museum in disused oil tanks. There were also numerous members of the board of the UCCA in Beijing. Others included Adrian Cheng, who opened the most recent of his K11 Art Foundation spaces in Hong Kong earlier this week.

Blum & Poe sold Henry Taylor’s large 2013 painting Queen & King for $850,000 shortly after the fair opened. The gallery also sold a piece by 60-year-old Japanese artist Yukinori Yanagi, Wandering Position – Pgonomyrmex7 (1997), which the artist made by using a red crayon to follow the wanderings of an ant. It went for $65,000; the gallery recently began representing the artist.

Newcomers to the fair include Paula Cooper, Regen Projects, and Matthew Marks, the latter showing a selection of paintings and sculptures by Kenneth Price, a 2017 Katharina Fritsch sculpture of a strawberry in cobalt blue, and a floral diptych of enamel paint on aluminum by Gary Hume, whose solo exhibition at the gallery’s L.A. space closes this Friday.

“Hands down, this is the best fair in Asia right now—every year just gets bigger and bigger in terms of the audiences and quality,” said Roshini Vadehra of the New Delhi–based Vadehra Art Gallery, whose works, including those by conceptual artist and photographer Shilpa Gupta that question national borders, are shown alongside didactic introductions. “People are unfamiliar with Indian artists, and are too shy to ask questions,” Vadehra said.

The relative obscurity of artists from regions outside the celebrated mainstream art world means that some dealers have to work that much harder for the attention of collectors. “I believe the struggle here is perhaps about outreach,” Art Basel Hong Kong’s director, Adeline Ooi, said. “If you explore the sort of programs and activities that a lot of Asian galleries do, I think they also take on an educational role where the commercial also becomes a little bit of a nonprofit.”

For some, participation can literally be a nonprofit affair. Taipei-based dealer Chi-Wen Huang annually takes a loss for her participation in the fair, but continues to present her booths as curated group exhibitions every year. Art Basel Hong Kong, she said, provides a major platform of visibility for her artists. The sexually and politically provocative themes of her exhibition this year, titled “Enka ! Platform for Change,” for example, would not have a venue in Mainland China’s conservative climate.

Like Tsui in the South China Morning Post, Meli Angkapradipta of Jakarta’s Nadi Gallery also questioned the strength of the current global economy. Having shown at the fair longer than it’s been part of the Art Basel brand, she’s noticed that her sales have been in decline in recent years, but like Huang, continues to return for the sake of global recognition for her artists. “Indonesian artists have good potential, and I believe that internationally, they should know about us,” she said.

After showing in the Galleries sector during previous years, Manila-based gallery 1335/Mabini presented works by Jill Paz—mannerist-style images laser-cut onto overlapping sheets of cardboard—in Discoveries, the sector devoted to newly commissioned works by solo emerging artists. Rather than showing several artists in the main fair, according to gallery associate Marie-Theres Steingassner, Discoveries proves to be a more strategic platform. “The artist really has the opportunity to explain herself, unlike in a Galleries booth where it’s not so easy to reach out,” she said.

Another gem is the display of ceramic sculptures by Lubna Chowdhary in Mumbai-based Jhaveri Contemporary’s Discoveries booth: these are collages of brightly colored architectural ceramic cutouts leaning on the booth’s perimeter that suggest fictional skylines. This is Jhaveri Contemporary’s third year in the sector. “We’re giving people an opportunity to get to know us, the work, the program,” said owner Priya Jhaveri. The art fair is a long game, she added, “or that’s what I tell myself.”

[ad_2]

Source link