[ad_1]

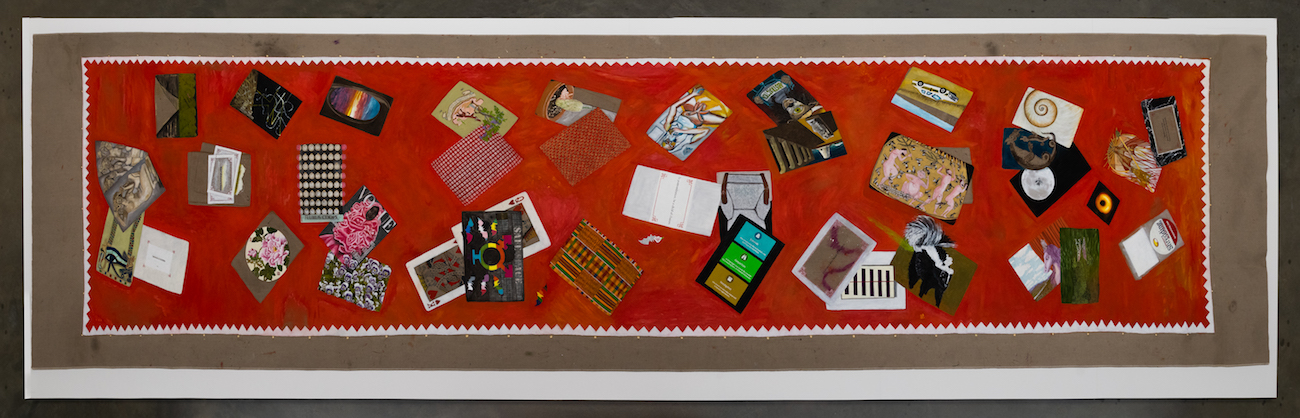

Installation image of “Leidy Churchman: Crocodile” at the Hessel Museum of Art.

CHRIS KENDALL

When Leidy Churchman was given the floor for his first museum survey since starting out as a painter, he did not squander the opportunity. Nor did he fail to take the proposition literally—with a 32-foot-long floor painting that serves as a sort of stream-of-consciousness survey of its own.

“It’s like another show in it,” the artist said of a new work taking special pride of place in “Crocodile,” an exhibition spanning Churchman’s career dating back to the mid-2000s at the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. “I thought I should do something big and abstract, but I don’t really plan much in advance. I didn’t know I was going to do this.”

When we met up, Churchman was in his studio on New York’s Lower East Side, and he was not yet finished with the floor work that would soon travel up to the Hudson River Valley. Most of it was complete, but there were some final tweaks and tinkerings to be considered. The painting, titled Don’t Try to Be the Fastest (Runway Bardo), features some 40 smaller paintings within it, all of them connected—or disconnected—in ways that can be difficult to describe.

Installation image of “Leidy Churchman: Crocodile” at the Hessel Museum of Art.

CHRIS KENDALL

“I think of the whole thing as a sort of mind,” Churchman said. “I’m always painting about the mind in a way. There’s this idea of emptiness in Buddhism that is hard to comprehend—that emptiness is not something that doesn’t have anything in it [but] is about the in-between between everything. It made sense to put all these pictures together in space. I think of it as bumper boats or something like that.”

The subjects that double as bumper boats vary: playing cards, a skunk, a Vogue magazine cover, E.T. and Elliot hover-biking in front of the moon, a pink pony, a painting by Giorgio de Chirico, a sunset spied through the window of an airplane. All of it together covers the kind of ground that Churchman focuses on in his practice as a whole (two mini paintings inside the floor painting are already-extant works of his own), and fittingly, perhaps, that practice can be intriguingly elusive.

Installation image of “Leidy Churchman: Crocodile” at the Hessel Museum of Art.

CHRIS KENDALL

Here’s fellow artist Alex Kitnick, writing about Churchman’s work in the “Crocodile” catalogue (a handsome new tome published by Bard’s Center for Curatorial Studies and Dancing Foxes Press): “There are patterns here, just as there would be in an archive of web searches, but there is also a radical juxtaposition between things that are hard to make coherent. The shape of the constellation is big and diffuse.” And then: “His interest, I think, is less in burrowing into things and reading them than in moving around their edges. Once, someone might have called that superficial, but today it might be one way of sensing (not making sense of) the glut of the world.”

Lauren Cornell, who curated “Crocodile” from her post as director of the graduate program and chief curator at CCS Bard, said of Churchman, “He’s evolved into a painter who can do anything, from complicated abstractions to intricate landscapes or portraits. What he puts in his paintings has always felt very timely. He paints the people around him and things he cares about. His painting tracks his preoccupations in a way, whether he’s looking at other artists’ work or thinking about different philosophies or books he’s reading or an awning on a restaurant across the street from his studio. I appreciate how over time he has created a kind of visual lexicon or archive of him and his life and interests.”

Installation image of “Leidy Churchman: Crocodile” at the Hessel Museum of Art.

CHRIS KENDALL

Cornell said she sees the floor painting as “a kind of key for the show,” and Churchman spoke of the special significance of its placement in front of another work, Disappearing Acts (2019). That one is a wall-hung painting of a scene from one of Bruce Nauman’s recent Contrapposto Studies videos, in which he walks in a pose privileged in classical European sculpture (hands clasped behind head, hip thrust out) and exaggerates it in a manner that is pointed, playful, and preposterous all at once. “He looks like he’s walking a runway,” Churchman said of Nauman, “and it gives it a movement that is nice.” (Hence the Runway Bardo part of the title, the artist explained: “Bardo” is a Tibetan-Buddhist word for “the in-between.” And then “Disappearing Acts,” the name of the big recent Nauman retrospective in New York and Basel, Switzerland, intimates Buddhist notions of erasure.)

Churchman’s mind seemed to wander, by design, as he walked around the floor painting in his studio, trying to size it up. The idea to make it sprang from the mode of reflection that attends the process of organizing a survey show with some 60 works—”showing all your cards,” as he said with a nervous grin akin to the look of the gritted-teeth emoji.

He was in good hands, he said, with Cornell, a friend of nearly two decades with whom he worked closely on the show, which runs into mid-October. “She was one of the first people to buy a painting from me,” Churchman said. “It’s a flying carpet with an ocean and these cats and bears in telephone wires. I’m in it and I’m throwing up on the rug. It’s on stained wood and looks like Maine folk art. But that was major.”

Leidy Churchman (middle, black shirt) at the opening of “Crocodile.”

LISA QUINONES

As he spoke, one couldn’t help but be curious about a tattoo of a watch on Churchman’s wrist. “I wanted to get the time of the tattoo, but it turned out I was getting it at 4:20,” he said. “So I got my birthday time, which was 9:08. In ads it’s always 10:10, because it looks like a smile. At 9:08, it looks like a smirk.” (Another clock was stitched onto his button-down shirt: “At Muji you can pay $3 and get a lot of different things embroidered. I have a sweater with a praying mantis.”)

In mind of the fleeting nature of thoughts surrounding the subject matter he paints—especially in the disparate Don’t Try to Be the Fastest (Runway Bardo)—Churchman turned contemplative and open-ended. “I’m trying to think of all the ways that things get torn apart and then move along and come back and reemerge—things that don’t make sense and do make sense, and all the emotions that come with them. I guess it’s a place where all these things and all their different elements can just be there.”

Looking down at the painting at his feet, he asked, “Does it feel like they’re all hitting each other, or like they’re transferring codes? As long as it brings you to thinking about how your mind works…”

[ad_2]

Source link