[ad_1]

By DeShawn Blanding and Danyelle Solomon

Asian Americans are facing physical and economic abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since the first report of COVID-19 on American soil, Asian Americans, especially Chinese Americans, have endured physical and economic abuse at the hands of their classmates, neighbors, and fellow citizens. Earlier this month, in New York City, a woman was physically assaulted while walking to the subway. For weeks, hate groups and elected officials at the highest levels of government have used racist scapegoating language to stoke fear, bias, and blame. These actions have produced a rash of hate incidents and xenophobia targeting Asian Americans. If left unaddressed, hate, like any virus, will continue to spread. Lawmakers must act now to combat misinformation, mitigate hysteria, and protect vulnerable communities.

Throughout U.S. history, pandemics and epidemics have bred misinformation, hysteria, and scapegoating, ultimately leading to a surge in racial and ethnic discrimination. For example, in 1892, a cholera crisis led public officials to discriminatorily quarantine Russian Jewish immigrants in Europe and New York City. In 2003, businesses turned away Asian American customers and customers boycotted Asian American businesses after media outlets began associating the SARS virus outbreak with people of Asian descent. In 2009, Latinx Americans were scapegoated after anti-immigrant hate speech spread on talk radio and online associating immigrants from Mexico with the H1N1 pandemic. The World Health Organization recognized the danger of misinformation and stigma when, in 2015, it issued guidance for naming novel human infectious diseases, recommending that they do not include geographic locations, people’s names, or cultural or population references.

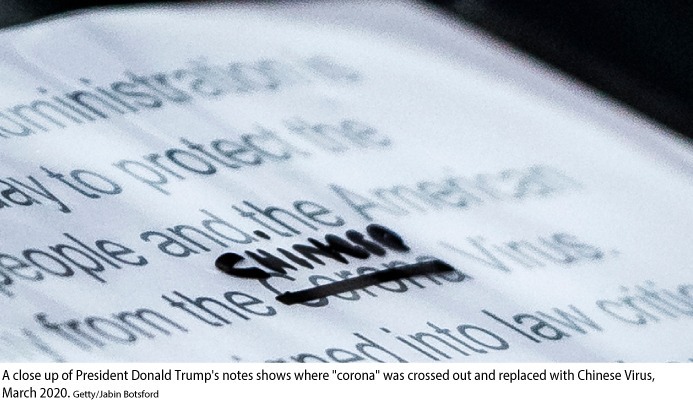

Despite guidance from the World Health Organization, Trump administration officials, including the president himself, have routinely referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” “Wuhan virus,” and even “Kung Flu”. Weeks ago, the Centers for Disease Control warned that associating COVID-19 with persons of Asian descent could create fear and anger towards Asian Americans and subject them to social avoidance or rejection; denials of health care, education, housing, or employment; and even physical violence. These warnings have borne out as reports emerge of a spike in anti-Asian hate incidents across the country. Between January 28 and February 24, San Francisco researchers reported over 1,000 cases of xenophobia against Chinese American communities. In New York, there have been multiple reports of physical attacks and vitriol against the Asian American Pacific Islander community, often accompanied with derogatory and racist verbal abuse. In California, one incident ended with the hospitalization of a 16-year-old San Fernando Valley student. In Indiana, two Hmong men were denied a hotel room out of fear of coronavirus. Nationwide, Asian Americans experience blatant and subtle microaggressions, invoking social exclusion, racism, and fear-based backlash. Asian Americans have even reported that sneezing and coughing can trigger harassment and violence.

Asian American businesses have also suffered in the wake of widespread misinformation and social stigma. In New Mexico, a local Asian American business was vandalized with racist graffiti. This occurred just days after a Chinese student at the University of New Mexico endured a racist COVID-19 prank from his roommates. Prior to the mandatory closing of restaurants and businesses in communities across the country, Asian American communities also faced economic backlash as people were hesitant to interact with Asian businesses because of coronavirus fears. Jing Fong, the largest restaurant in New York City’s Chinatown, lost $1.5 million and saw a 50 percent drop in business prior to the city shutting down nonessential businesses. Many restaurants in the Seattle’s Chinatown have seen a significant drop in sales as well. These accounts demonstrate that even large, well-established businesses can experience serious financial hardships when officials do not work to limit the spread of misinformation and hysteria.

Some communities and elected officials have started acting. Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, Chinese for Affirmative Action, and the Department of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University have created a website to collect and track racist incidents. New York has launched a hate crimes hotline for residents. The San Diego County District Attorney Mara Elliott stated, “We are working together with all levels of government to target and hold accountable those who spread hatred and exploit residents while our community grapples with these difficult circumstances.”

More lawmakers must follow suit and fight back against this anti-Asian hate in communities across the country. At the very least, they should refrain from using geographic locations or groups of people when naming COVID-19; share only confirmed and verifiable information pertaining to the virus; condemn negative behaviors, including statements made by other public officials; engage with Asian American individuals and organizations in person and through media channels; and pass resolutions denouncing racism, xenophobia, and misinformation.

During this pandemic, Asian American families—like all American families—are concerned about their physical and mental health, job security, and their children’s education. Neither they nor any other racial and ethnic group should endure the added layer of terror that comes from a surge of hate crimes. Lawmakers must act now to reduce bias and protect America’s most vulnerable communities.

DeShawn Blanding is an intern for Race and Ethnicity Policy at the Center for American Progress. Danyelle Solomon is the vice president of Race and Ethnicity policy at the Center.

To find the latest CAP resources on the coronavirus, visit our coronavirus resource page.

[ad_2]

Source link