[ad_1]

A drawing by Molly Crabapple for the Black Sex Workers Collective, which is staging a protest today in Washington Square Park in New York.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Protests, advocacy-oriented exhibitions, and emergency fundraisers taking place yesterday and today, which has been dubbed International Whores’ Day by organizers, are bonding artists, activists, and sex-workers (sometimes one and the same) in opposition to FOSTA-SESTA, the recently passed law that curtails sex-workers’ communications online.

“Artists and their works containing some element of sexual content are collateral damage in the wake of FOSTA-SESTA,” Michael Macleod-Ball, a First Amendment adviser to the American Civil Liberties Union, said. “The bill’s proponents aimed at sex traffickers and those who facilitate sex trafficking online. But all it takes is one zealous prosecutor to go overboard in deciding what constitutes ‘facilitation.’ ”

FOSTA-SESTA packages together two laws amending the 1996 Section 230 safe harbor portion of the Communications Decency Act, which previously protected websites from being held accountable for users’ content. Promoted by celebrities like comedian Amy Schumer and Seth Myers with emotional appeals about curbing sex trafficking on classified-advertising sites like Backpage and Craigslist, the law was criticized by some law enforcement groups and media organizations, First Amendment experts, and many sex-workers, who say that it endangers them, but passed with bipartisan support in both houses of Congress.

Since President Trump signed FOSTA-SESTA into law on April 11, websites from fringe dating sites to Craigslist and Google Drive have taken steps to scrub sexual content and evict sex workers from their services, creating a virtual replica of Times Square during the Giuliani era. (Google has said such material violates its stated policies.) For opponents of the law, the tragic irony is that, while the internet created a viable community-oriented harm-reduction environment for consensual sex-workers, “FOSTA-SESTA creates the seedy underground civilians fear,” as artist and pornographic actor Zak Smith put it.

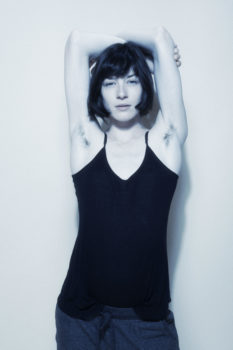

A portrait of Stoya by Clayton Cubitt.

“Sex workers who escort and relied on ads to stay off the streets are scrambling, just like they warned they would be,” Stoya, a pornographic actress and frequent creative collaborator with artists Molly Crabapple and Clayton Cubitt, said. “I’m hearing third-hand reports of people disappearing and of pimps contacting workers pretty intensely during the first few days after the law was approved by Trump—just like sex workers warned would happen.” Arabelle Raphael, a pornographic actress who has modeled for painter David Nicholson, elaborated on Stoya’s reference to sex workers’ disappearance in a Huffington Post piece, asserting that financial pressures the law places on sex workers to return to predatory clients has already resulted in rapes and assaults.

A climate of fear is confirmed by Leah Schrager, whose Instagram persona ONA masterfully straddles boundaries between sex-work and art. She said, “This law has been devastating, particularly for escorts, but in general I sense anyone involved in sex work—cam girls, porn performers, just anyone who broadcasts a sexualized image—is scared. Without the ability to promote what we do, and to communicate with each other to make sure we’re only dealing with good people, our incomes, our careers, our ambitions, and our safety are deeply jeopardized.”

However, proponents of the new law, like the advocacy group World Without Exploitation, say that it helps combat online sex-trafficking. “FOSTA-SESTA is a response to a grave injustice that disproportionately impacts women and girls of color, most who have landed in the sex trade not because of choice, but because of lack of choices or coercion,” Lauren Hersh, the national director of WWE, told Teen Vogue earlier this year.

A work by Leah Schrager.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Sex work is a rare subject where conservatives and some feminists are united in advocating steps that opponents of the new rules say suppress and stigmatize the voices of women and other sexually marginalized groups, but artists have historically found meaningful inspiration in the emotional labor, commercialized intimacy, mutual needs, psychological intricacies, and sexual empowerment found in selling sexual services. As Eric Sprankle, an associate professor of psychology and sexuality studies at Minnesota State University, put it in an often-cited tweet: “If you think sex workers ‘sell their bodies,’ but coal miners do not, your view of labor is clouded by your moralistic view of sexuality.”

Sex-positive feminists, like author and film director Liz Goldwyn, argue that deep threads of misogyny have motivated support for FOSTA-SESTA as well as resistance to decriminalizing sex work. Goldwyn, whose decades-long research into the history of prostitution formed the foundation for her recent novel Sporting Guide, said, “We canonize rappers who sling crack at the start of their career to own their master recordings—i.e. Jay Z, Biggie Smalls, etc. Yet women, who have had so few choices of profession until the last 100 years, are shamed for how they put food on the table.”

In today’s gig economy, women are not alone relying on sex work as an auxiliary income steam. As Vice reported in 2017, part-time sex work is sometimes a significant source of funds for students and creative people, of all genders, in prohibitively expensive cities. Adding specifics about the financial ramifications of the law, Smith, the artist and actor, said that some banks have closed accounts of people working in the pornography industry—“in some cases, freezing peoples’ savings. Google Drive has erased or frozen thousands of dollars’ worth of content that sex workers trustingly stored there—videos legally made and paid for. People like to categorize folks as either celebrities or victims but not both, so it’s hard for them to feel sympathy for porn peoples’ problems but the fact is three months ago we had a legal job and then suddenly we are not allowed to use our ATM or credit cards.”

A work by Zak Smith.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Artists, including Crabapple and Schrager, are responding to the current crackdown by contributing work for benefit exhibitions and protests like “One Night Stand,” which was held the Euridice Gallery in Brooklyn last month, and an “International Whores Day of Action” presented today in Washington Square Park in New York by the Black Sex Workers Collective. Supporting artists’ friends and muses in the sex-work community, these events contribute to the Lysistrata Mutual Care Collective and Fund. Olive Glass, a Penthouse Pet who has also posed for David Nicholson, is hosting a fundraiser because, as she sees it, “this law is just another stepping stone in the path of oppression, especially for those artists who attempt to push the boundaries of sexuality.”

Right now, such efforts are aimed at drawing attention to the law’s underlying effects on marginalized and vulnerable groups, providing offline platforms for sex workers to be heard, and underscoring the law’s threat to artistic expression. Depending on the eventual outcome of the advocacy work, the opposition to FOSTA-SESTA within the sex-worker community might become an opportunity to begin broader societal conversations about decriminalization and recognition of sex-workers as service providers working in an unregulated and vulnerable but massive industry.

Sex-positive feminist and pornographic film director Nina Hartley described the position of FOSTA-SESTA opponents succinctly: “If Congress really cared about the health and safety of those in sex work they would adopt the harm-reduction model, which seeks to empower individuals to take control of their lives, be it to leave sex work or stay.”

[ad_2]

Source link