[ad_1]

Conceptual art was a wide phenomenon which has brought different and entirely innovative art practices in general focused around the ideas of rejection of dematerialization of the artwork, deconstruction of the language and the institutions, as well as the rejection of the art market.

Throughout the 1970s, a large number of young artists started producing conceptual works, yet only the most focused ones managed to continuously sustain and keep their practice fresh. One of them is Charles Gaines, a Los Angeles-based artist, writer, and lecturer.

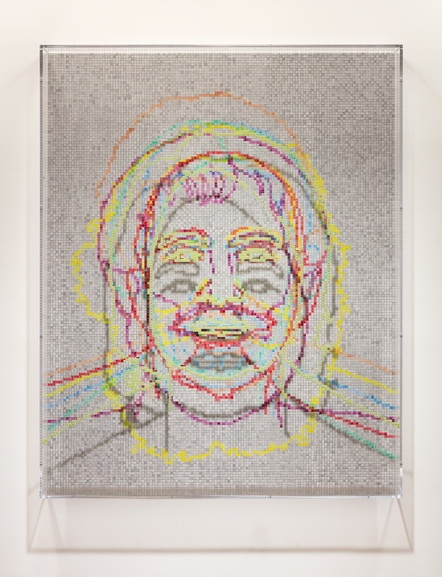

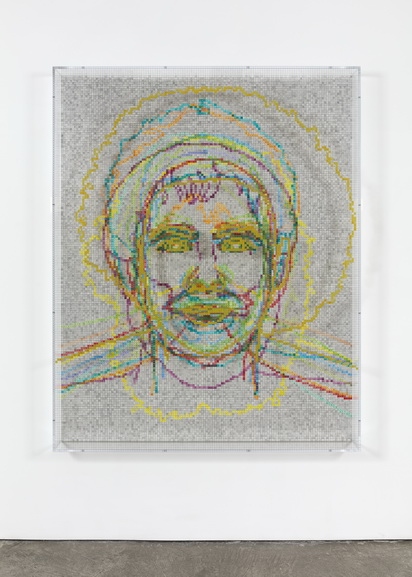

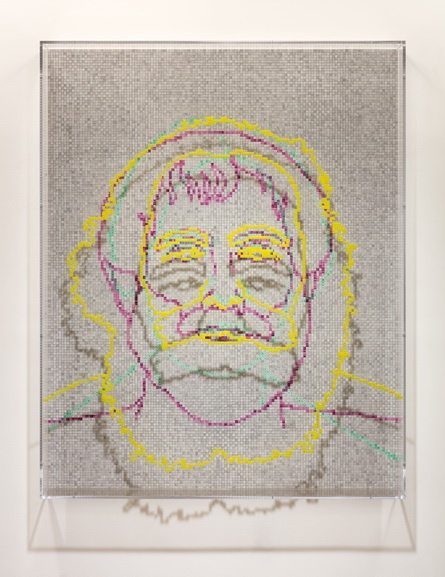

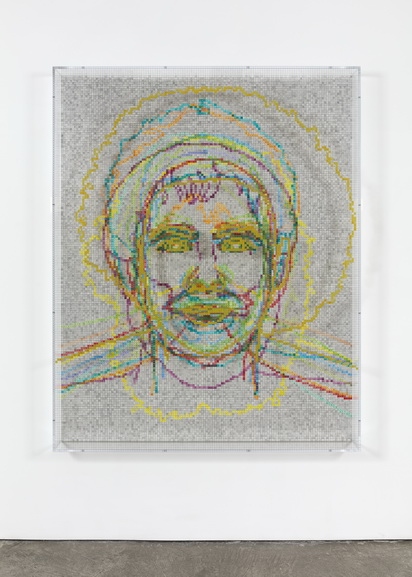

His new exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York, a particular installment titled Faces 1: Identity Politics and on view through June 9, 2018, continues to examine the relationship between the language and the images; aesthetics, politics, language, and systems are being examined in the manner similar to the one present in his series Faces (1978-79).

Namely, the artist has produced twelve large-scale serialized works centered around the characters of famous thinkers – from Aristotle, over to Karl Marx and bell hooks. These outstanding multifaceted portraits or panels, which could be described best as hybrid forms (due to the intersection of manual and digital process), are contrasted with the musical scores titled Manifestos.

We have asked Charles Gaines to deliberate a bit more about the exhibition, as well as to comment his practice in retrospect and in the contemporary moment.

The Continuity of Charles Gaines – Initial Ideas in New Formats

Widewalls: The occasion for this interview is your current exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery, so I have to ask you: how much did your artistic practice change over the years? Were there any specific turnovers which you find crucial for the change or has the exploration of the dominant themes in your work just expanded?

Charles Gaines: My practice changed around 1993. In 1973, I started working with numbers and systems. The grid was the structure I worked with. In ’93, I began working with the language itself. Language structure replaced the grid.

What was consistent was my interest in interrogating representation. My view is that art at the time regarded representation the product of psychological expression of the artist. It also regarded representation not as a semiotics but as an aesthetic and or as an empirical act, meaning the representation was based upon an experience or truth that was not directly observable but reliably represented through expression.

I though representation was a cultural construct and a semiotics. Also, I believed that the relationship between the object and its representation was arbitrary. Only cultural agreement made it meaningful.

Widewalls: The important segment of your work is music. You were without a doubt a follower of John Cage, so the notable aspect for any further articulation is indeterminacy. On the other hand, you have worked with Tricia Brown on her piece Son of Gone Fishin, where the grids as well present in these works do appear. In the exhibition the audience can experience musical scores under the title Manifestos, so could you explain these works, also from the historical stance (what was the avant-garde music then and what is now)?

CG: Manifestos is a gallery installation made up of video monitors and large drawings of musical scores. To produce it, I researched political manifestos and essays from the past to the present. In Manifestos 3, I selected two essays, a James Baldwin essay, “Princes and Powers”, and a written speech by Martin Luther King given in England.

I translated the text into musical notes. I did this by developing a system whereby the letters of the alphabet that are used in musical notation (letters A through G) are converted to notes. I also converted H to Bb, honoring a Baroque musical tradition. I wrote this out for piano.

There is a melody line where the letters are converted to notes. Letters that are not used in musical notation are scored as silent beats or rests. The piano score forms the harmony line. Each word produces an accompanying chord. I realize this by selecting the first letter in a word that is used in music to its chord. For example, in the word “dog” the first letter used in musical notation in that word is “g”.

So this is scored as a G chord. I have a system where the chord scoring is sequenced. So the G chord is either a major, minor, augmented or diminished chord, depending on its position in the sequence of chord notations. I then take this raw translation and arrange it for piano. My rule is that I can take the available notes to produce musical phrases, but I cannot add notes or subtract them.

We record the arrangement in a sound studio. Then in the installation, the text is scrolled on a video monitor while the music it produced is played. Also in the installation, I make large-scale copies of the music score. One can also see the original text on the score and how the letter to note translation was done.

The music sounds atonal but it is quite tonal. The reason is that I use the diatonic Western music scale. The piece is shaped by a system that randomizes the music’s relationship to the text. The music informs the experience of the text, which seems intentional, but in fact, it is not, because the system makes the decisions.

I shape the decisions of the system but do not introduce anything new. I was influenced by Cage but also the I Ching and Steve Reich. There is a performance version of each installation that I have performed, not Manifestos 3 yet, but I have performed Manifestos 1 and 2. In this situation, the text scrolls on the screen behind the ensemble that is performing the music.

The Domains of Engaged Practice

Widewalls: Besides the apparent craftsmanship, my impression is that the shown works and the conceptual approach is rather ideologically charged. Could you tell us a bit more about the selection of thinkers to which you referring to?

CG: The title of the work is Faces: Identity Politics. I selected the images of thinkers who were part of the development of the Western theories of self, identity and the idea of the human, what is it to be human. They run from Aristotle to bell hooks.

The mathematical layering of their faces is supposed to operate on one level as a metaphor for the historical development of the idea of the human, demonstrating that such an idea is part of the Western body of knowledge that spans back at least 2000 years.

This is an attempt to critique the conservative agenda and its mission to trivialize political ideas of race and difference as they apply to the history of racism and segregation. The right wing has accused minorities and their supporters of “playing the race card” when minorities critique the presence of white supremacy and how it has produced an uneven playing field in a society that privileges white people. They reduce the term to simply an attempt to support an agenda of affirmative action, which to them gives minorities privileges they don’t deserve.

The work attempts to highlight how white supremacy has tried to redefine the concept from that of being an intrinsic part of our understanding of the human to a political weapon which is not based in knowledge but opportunism.

Widewalls: Do you find your own work partly as a reflection of contemporaneity e.g. present-day social and political currents? The portraits at Paula Cooper Gallery could be perceived as airport security scans or even hi-tech military targets. Therefore, one comes to the conclusion that the exploration of racial topics, which has been present in your work from the start, embarks on a new level?

CG: I am not directly interested in the politics of digital representation and its use to control populations.

My interest in the grid goes back 40 years when I produced the first works in the 70s. At the time, the digital representation was not even a thing, at least something that had social importance. My use of it was to employ a system to produce a work of art; my critique was to the received idea that artworks were produced by self-expression, a modernist theory that presupposes the idea of a subject that expresses through an art language such as painting or sculpture. It is offered as the principle that universalizes art in that the subject that expresses does so through the universalizing language of art.

I questioned this because this idea dismisses issues of culture and difference and their role in art. I proposed that works of art can be produced by systems by employing them to make artistic decisions rather than the intuition. This had a further interest in de-essentializing art practice, by showing the arbitrariness of representation, which differs from the modern idea that the expression itself is a metonymy of the subject (cause and effect where the expression is the effect of an unseen agent, the subject.

My attitude about representation allows the re-entry of culture and politics, which, in this work, engages in a political critique of the idea of identity and the human. It’s fine to think politically about the subject in the way you express, as a “big brother” tool, but you have to broaden the context to remember that I have been working this way since the early 70s, I first produced Faces in 1978, where I used systems as a critical and political tool, not the object of criticism as, for example, a critique of strategies of control and dehumanization.

The Artistic Positioning of Charles Gaines

Widewalls: Since you do belong to the first generation of Conceptual Art, I am interested: how do you perceive the art market and overall commercialization of the visual arts?

CG: I have not problems with the idea of an art market. Artists have to be paid for their work. But today, the problem seems to be that the market has taken over the responsibilities of determining value from historians, critics, and museums.

And especially since many conceptual artists were prolific writers, the voice of artists is almost absent. This I find a real problem because I regard art as one of the disciplines that participate in the acquisition and accumulation of knowledge about the world. It is a major source of ideas, ideas that help shape our understanding.

The present situation has produced a space where ideas have very little negotiable power, so they are not tested against history. Art seems to function as one of the ways to measure markets these days as ideas suffer and are replaced by effect only since the effect is more commodifiable. I am not pessimistic, though, I think it will change, that is why I write as well as make art.

Widewalls: How do you perceive the acknowledgments in regards to rewards, honors, and even retrospectives? What does it mean for an artist who is present on the scene for almost four decades? Does such an appraisal encourage the artist to keep on broadening his creative boundaries or does it allow him to remain loyal to his artistic manner?

CG: By the time one is offered a retrospective, an artist has had too many experiences in making art to respond to attention in the way a young artist might.

Widewalls: You are also an acclaimed author and a lecturer, which certainly contributes to your work as an artist. Therefore, at the end of this brief, yet rather exciting interview I would like to ask you about your further plans?

CG: I am working with DIA to produce a major project. Also, I am working on an opera on Dred Scott, Fred Moten is writing the libretto. There are two publication projects coming up that are in a stage too early to discuss.

Editors’ Tip: Charles Gaines: Gridwork 1974-1989

Considered against the backdrop of the Black Arts Movement of the 1970s and the rise of multiculturalism in the 1980s, the works in Charles Gaines: Gridwork 1974-1989 are radical gestures. Eschewing overt discussions of race, they take a detached approach to identity that exemplifies Gaines’ determination to transcend the conversations of his time and create new paths. The publication gathers significant examples from several of the artist’s most important series, including 75 key works from the mid-1970s through the late 1980s. It features drawings and photographs from public and private collections–some of which were previously considered lost–and essays by leading scholars and curators.

Featured image: Charles Gaines. Courtesy of the Artist. Photography by Katie Miller. All images © Charles Gaines, courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

[ad_2]

Source link