[ad_1]

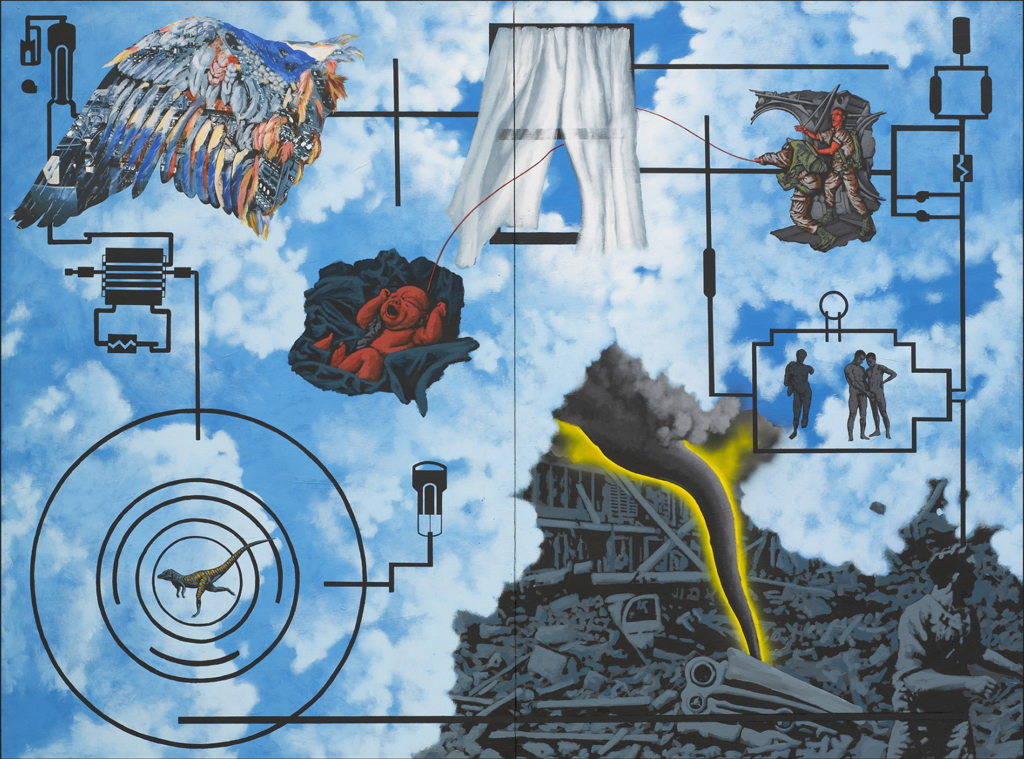

David Wojnarowicz, Wind (for Peter Hujar), 1987, acrylic and pasted paper on wood, two panels.

COURTESY THE ESTATE OF DAVID WOJNAROWICZ AND P.P.O.W., NEW YORK/MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK, PROMISED GIFT OF STEVEN JOHNSON AND WALTER SUDOL

As the end of the year approaches, we invariably begin to reflect on the preceding 12 months—our victories and losses, our moments of love and joy and pain, and, maybe, some of the best art we saw this year. For me, alongside all the sickening political developments and harrowing stories of survival I heard about this year, two shows and one work have lingered in my memory: a David Wojnarowicz retrospective at the Whitney Museum in New York, the 2018 SITElines biennial at SITE Santa Fe in New Mexico, and Liliana Porter’s new performance, THEM, at the Kitchen in New York. All three touched on the aching pain associated with loss and marginalization, calling on us to remember the victims of violence and trauma. What was lost was not necessarily easily forgotten at these three affairs.

Memory is central to the work of Wojnarowicz, who looms large in the history of art during the height of the AIDS crisis, in the 1980s and early 1990s. So palpable is the sense of loss in his work that I can only describe it by pointing to one viewer’s reaction during the Whitney retrospective’s opening. On that night in early July, I watched a tall queen in a mesh shirt and jean cut-offs (with an ass cheek exposed) enter a black-box room where some of Wojnarowiczʼs films were being screened, sit down, and begin to sob. He was seemingly inconsolable, but a friend joined him shortly after to provide comfort. I don’t know the exact reason that viewer cried, but I, too, found myself in tears—multiple times—as I walked through the show the first time. It’s a common reaction to Wojnarowicz’s work. To see art from his generation is to feel the artist’s pain and loss, as well as the space left empty by his absence.

The most deeply touching example of this came in the images and text related to the photographer Peter Hujar (who was also the subject of an insightful retrospective in New York this year, at the Morgan Library and Museum). Wojnarowicz and Hujar met around 1981, were briefly lovers, and became lifelong friends, with Hujar, 20 years Wojnarowicz’s senior, becoming a mentor of sorts to Wojnarowicz. In Wind (for Peter Hujar), part of “The Four Elements” series, Wojnarowicz presents a mostly blue composition, consisting of various small scenes all interconnected. In one, a screaming newborn baby painted in red is connected via an umbilical to a pair of paratroopers about to jump—one headless, the other a self-portrait. The cord passes throw an open window with white curtains, one of which has caught the breeze, symbolizing “for Wojnarowicz, a dream associated with impending death,” according to David Kiehl in the exhibition’s catalogue. To the left of the window is a rendition of a Dürer postcard of a bird’s wing that Hujar owned. When Hujar died a few months after the work was completed, Wojnarowicz created a Super 8 film of the room and a suite of 23 photographs of Hujar’s body, among them of his still-open eyes and mouth, his right hand with darkened fingernails, and his feet. When talking about the Wind work three days later, Wojnarowicz said of Hujar, “He sees me, I know he sees me. He’s in the wind in the air all around me.”

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled, 1988, gelatin silver print.

WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART, NEW YORK

Wojnarowicz’s career was also cut short—he died at age 37 in 1992 of AIDS-related causes—but he produced some of the most powerful images of his era: buffalos falling over a cliff, ants on a cross, a little boy surrounded by text, a face emerging from the sand, a man with his lips bloodied and sewn shut. Like much of his cohort, Wojnarowicz operated at the margins of society and the art world. He was a hustler early in life, a self-taught artist, and a confrontational activist who was focused on his day’s most pressing topics, including U.S. intervention in Latin America, capitalism and the poverty it engenders, and, of course, the AIDS crisis. Working at the periphery seemed to be where he felt most comfortable—even as his work achieved critical acclaim. At a certain point, he moved from the outside in.

Curated by David Breslin and David Kiehl, the Whitney’s hotly anticipated retrospective was ten years in the making, and it did not disappoint. In these tumultuous times, the show resonated. It evoked loss on both physical and metaphorical terms—one of the best galleries, an empty room that looked out to the Hudson River, where the piers, a gathering and cruising place for Wojnarowicz and many queer New Yorkers, once stood, featured recordings of the artist reading excerpts from his writings. Wojnarowicz’s disembodied voice—a poignant reminder of the void that the dead leave behind—sounded like a ghost from the past calling out to the present. At one point, he could be heard saying, “There’s a thin line, a very thin line and as each T cell disappears from my body it’s replaced by 10 pounds of pressure, 10 pounds of rage, 10 pounds of pressure, 10 pounds of rage. . . . America, America, America seems to understand and accept murder as self-defense against those who would murder other people.”

Rage was the emotion Wojnarowicz was best at channeling. He was angry, and rightfully so. He witnessed politicians—including George H. W. Bush, then the President of the United States—let millions die rather than respond to a mounting epidemic in a timely fashion. This is, of course, topical—and maybe the show was timely in ways the Whitney didn’t expect. The same month the show opened, the New York chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), of which Wojnarowicz was an active member, staged a protest at the Whitney, alleging that the exhibition historicized not just Wojnarowicz but HIV/AIDS as a whole. The demonstrators claimed, by not connecting the exhibition to contemporary concerns about HIV/AIDS, Breslin and Kiehl were effectively saying that the AIDS epidemic had ended. The protestors brought with them signs that read in part: “When we talk about HIV/AIDS without acknowledging that there’s still an epidemic – including in the United States – the crisis goes quietly on and people continue to die.”

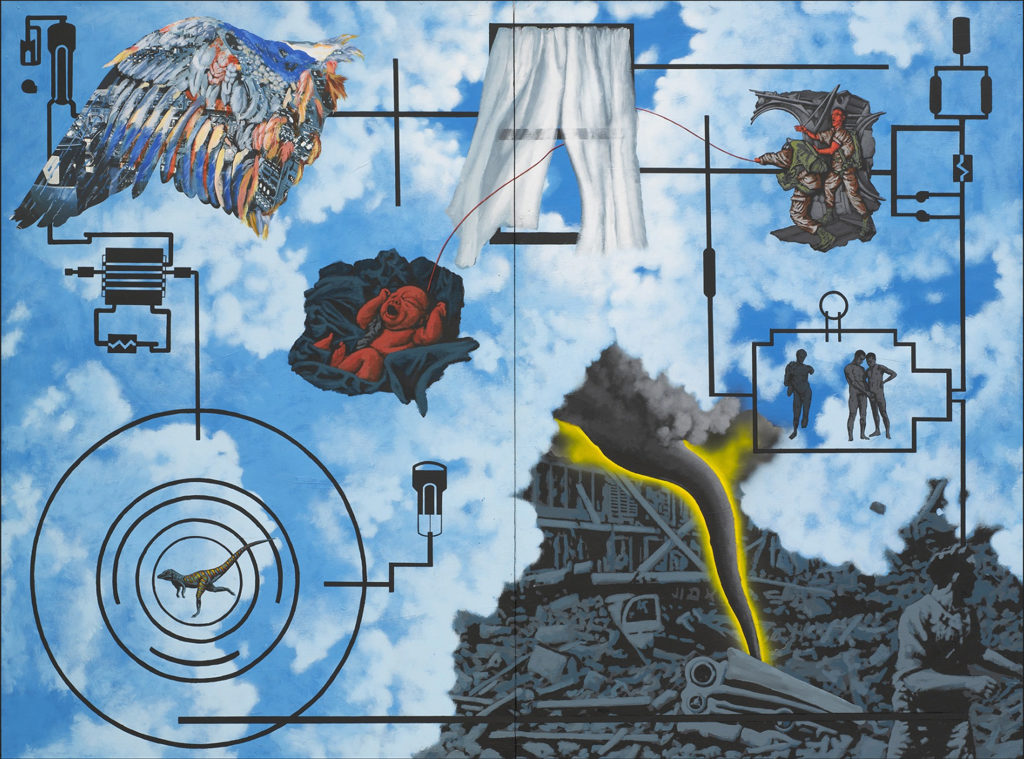

A detail of Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds’s commissioned series of monoprints and ghost prints collectively titled Surviving Active Shooter Custer.

MAXIMILÍANO DURÓN/ARTNEWS

Death of a different sort pervaded Surviving Active Shooter Custer (2018), a group of monoprints and ghost prints by Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds now on view at the SITElines biennial (through January 6). Each work presents a series of short, sometimes fragmented phrases against a monochromatic background; it draws on a range of sources—pop songs, common sayings, names from history and current events—to offer sobering ruminations on mass shootings. The artist believes gun violence is not a new phenomenon—we need look no further than the massacres of Native peoples throughout American history, he told me. One print makes General Custer out to be an active shooter, rather than a Civil War–era hero; it reads: “STOP / ACTIVE / SHOOTER / CADET / AUTIE / CUSTER.” In one touching print nearby, Heap of Bird inverts the common phrase “It is everyone’s pain,” turning it into “IS / IT / EVERY / ONES / PAIN.” Those words, once phrased as a statement, are now an open question.

This year’s SITElines, titled “Casa tomada,” was curated by José Luis Blondet, Candice Hopkins, and Ruba Katrib, with Naomi Beckwith serving as curatorial adviser. The show’s title—which translates to “house that has been taken over” or, more simply, “house under siege”—comes from a 1946 short story by Argentine writer Julio Cortázar about two bourgeois siblings living in their ancestral home in Buenos Aires. Slowly and inexplicably, they are forced out of sections of their house; finally, they leave it behind altogether. This felt like an apt title for the exhibition, which thoughtfully ponders that basic question of who belongs—in a biennial, in the art world, in society in general—and what it means to be left powerless, shut out of history.

Curtis Talwst Santiago, Walls to Divide, 2012, part of the ongoing “Infinity Series.”

MAXIMILÍANO DURÓN/ARTNEWS

Curtis Talwst Santiago picked up this thread with masterful glass house installation which presented 50 or so dioramas each made in miniature reclaimed jewelry boxes that are a part of his ongoing “Infinity Series,” begun in 2008. To look at them, viewers must stoop down and get close to see the intricate details Santiago has crafted in each scene, which include depictions of current events, everyday activities, personal history, and art history. In his 2012 miniature diorama Walls to Divide, which mostly consists of miniature bricks that form a wall in a small reclaimed jewelry box. Santiago told me he made it in response to feedback he received when he first started showing works from the series. “When I first started making those works and showing them to the art world, I was getting a lot of rejection, and it was never because the object wasn’t good,” he told me. “I always felt that it was about me being black. . . . I felt that this wall was impenetrable.” Seeing Walls to Divide now, I couldn’t help but connect it to the barriers that artists of color face in the art world—and also to talk of building a physical wall on the U.S.-Mexico border, which has now led to a days-long government shutdown.

Some artists in the show set their sights on art institutions themselves. Eric-Paul Riege, a generational Navajo weaver, staged a nearly-five-hour-long performance on the opening day in which he interacted with the installation he had created for the exhibition and took on animalistic gestures and movements. At one point during the performance, he walked around the museum and communed with several pieces in the exhibition, including works by Heap of Birds, Melissa Cody, and Fernanda Laguna, as well as with many of the visitors, coming up to each person individually and staring straight into their eyes as he stamped a walking stick. He told me later that it was a way to pass on to others the gift of weaving by mimicking the sounds of the loom. Andrea Fraser, meanwhile, showed diagrams from her 2018 book 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics, a 1,000-page tome that details the contributions that trustees at U.S. art museums gave to political organizations in the lead-up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Among the institutions surveyed is SITE Santa Fe, whose board members donated mainly to Republican causes that year.

On the other side of Fraser’s contribution, in a stunning installation titled Revindication of Tangible Property (2018), Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa reimagined a passage from the sacred Mayan text Popol Vuh, in which everyday objects rebel against their owners. The owners had been created by the gods, but the objects—vases and cooking utensils mostly—felt that their owners weren’t grateful enough for their creation, hence the rebellion. The installation was a subtle commentary on how a revolutionary act can start with those who appear commonplace or invisible, or even get forgotten. As he stood beside his work, Ramírez-Figueroa, pondering his inclusion in an exhibition about belonging, posed a question to me: “When I close my eyes, does identity mean anything?”

Decolonize This Place’s protest at the Whitney Museum in New York today.

ALEX GREENBERGER/ARTNEWS

One might find humor in the absurdity that is American life in 2018. While not necessarily a solution to the current era’s problems, comedy can serve as a temporary panacea for the woes of many. In October, I attended a performance of THEM, a theater piece by Liliana Porter and co-directed with artist Ana Tiscornia, at the Kitchen in New York. The performance, part of the programming for a Porter’s survey now on view uptown, at El Museo del Barrio, features a series of short vignettes with a cast of disparate characters performing in often absurd scenarios—a ringmaster trying to tame a stuffed animal lion, twins mimicking each other, a man with a mask staring at a stuffed duck.

The most unforgettable of these comes when an artist molds clay on stage, creating a misshapen sculptural work based on a model of Mickey Mouse. The piece quickly winds up at an unnamed auction house, where it is sold to the highest bidder after being touted through artspeak. (You can just imagine a celebrity auctioneer praising the work: What a fluid and rapid approach to sculpture she has!) In a time when the art market is viewed such seriousness and such veneration, this scene is a reminder that the best response to that which is ridiculous is to name it as such.

How best to change the world now? One solution could involve Porter’s ability to laugh at those in power. Another could make use of activism, which aims for equity and more ethical living. Since the Wojnarowicz retrospective and SITElines opened, I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on the two shows and the ACT UP protest, as well as the recent actions at the Whitney calling for the removal of Warren B. Kanders, the vice chair of the museum’s board. (A Hyperallergic report earlier this month revealed Kanders’s ownership of Safariland, a company that produces tear gas canisters and other products used against asylum seekers on the U.S.-Mexico border.)

Reading about the Kanders controversy, I can’t help but think about Whitney director Adam Weinberg’s own contribution to the catalogue for the Wojnarowicz show. In his foreword, Weinberg praised Wojnarowicz for the artist’s sensitivity to “the fundamentally conflicted role inherent to museums of contemporary art” as both the establishment and the “advocate[s] for outsiders, rebels, and revolutionaries who reject the boundaries of good taste and revile the attempt at a definition of art itself.”

He acknowledges that the museum’s “authority has to be both self-critiqued and continually kept in check by artists, the press, and others” and that the Whitney, like other institutions, “sometimes can and does stand in the way of progress.” And, sure enough, when it comes the Kanders situation, the art community has risen to the task, in the form of an open letter signed by 95 Whitney employees in which they called on museum leadership to consider asking for Kanders’s resignation. Shortly after that letter came out, a protest by the activist group Decolonize This Place was held in the museum’s lobby.

The exhibitions I’ve discussed and the ensuing protests at the Whitney remind us that we must constantly remember the powerless, the voiceless, and the marginalized, and that we must continue fighting on their behalf. Some among us are angry, and with good reason, about that which is pushed aside, left out, seemingly best left forgotten by those in power. They want us to think about who really wins when steps toward progress are achieved. What is lost in that which is gained? If we listen carefully enough to these shows—to Wojnarowicz’s voice, to Heap of Birds’s prints, to Porter’s absurdism—we might start making some steps in the right direction. As Hopkins puts it in her essay for the SITElines catalogue, “Art has a transfiguring capacity that allows us to hear in moments of silence, to open our ears rather than to close them.”

[ad_2]

Source link