[ad_1]

Years ago, into the surface of the earth, Nicholas Galanin carved a petroglyph of the kind found on rocks and mesas in expansive landscapes around the globe. It tapped into a lineage of ancient artworks whose meanings can be simple and complex in ways that take ages to reveal themselves in full. But the pattern of this petroglyph was unique—in the form of the word “Indians” as styled slightly cartoonishly by the Cleveland Indians baseball team. And the expansive landscape was denser than most—on a sidewalk along a stretch of Wooster Street in the downtown New York district of SoHo.

That interventionist gesture happened back in 2011—which feels like an eon ago for an artist whose star has been on the rise. Last year, Galanin exhibited one of the defining works in the Whitney Biennial, and he made news when he joined a group of artists in a high-profile call to have their work removed from the museum in protest of since-departed Whitney board chair Warren B. Kanders. Now, Galanin is back in New York—from his home in Sitka, Alaska—with “Carry a Song / Disrupt an Anthem,” his first solo gallery show in the city.

The sculptures, paintings, textiles, and installations in the exhibition, at Peter Blum Gallery on the Lower East Side, focus on Galanin’s standing as a Tlingit and Unangax̂ artist exploring Indigenous identity and various conceptions and misconceptions surrounding it. “To balance out the diversity of medium and process was, as always, interesting because I do a lot of different projects,” Galanin told ARTnews during a walkthrough of the exhibition. (As he wrote in Kindred Spirit: Native American Influences on 20th Century Art, a book published around an earlier group show at Peter Blum: “I work with concepts, the medium follows.”)

“These are maps and exit routes for cultural objects from institutions,” Galanin said as he pointed to two new works made over the past year on deer hides pinned to a wall. The first—Architecture of return, escape (Metropolitan Museum of Art)—has arrows charting ways out from where Northwest Coast objects are kept at the Met, and the second—Land Swipe—shows greenspaces and underground transit patterns in Manhattan that used to be Indigenous travel routes in the past. Both address “the simple fact that objects often were removed from communities forcefully or through theft,” Galanin said—but also diverging perspectives on “care for cultural objects, and repatriation and restitution as forms of oppression.”

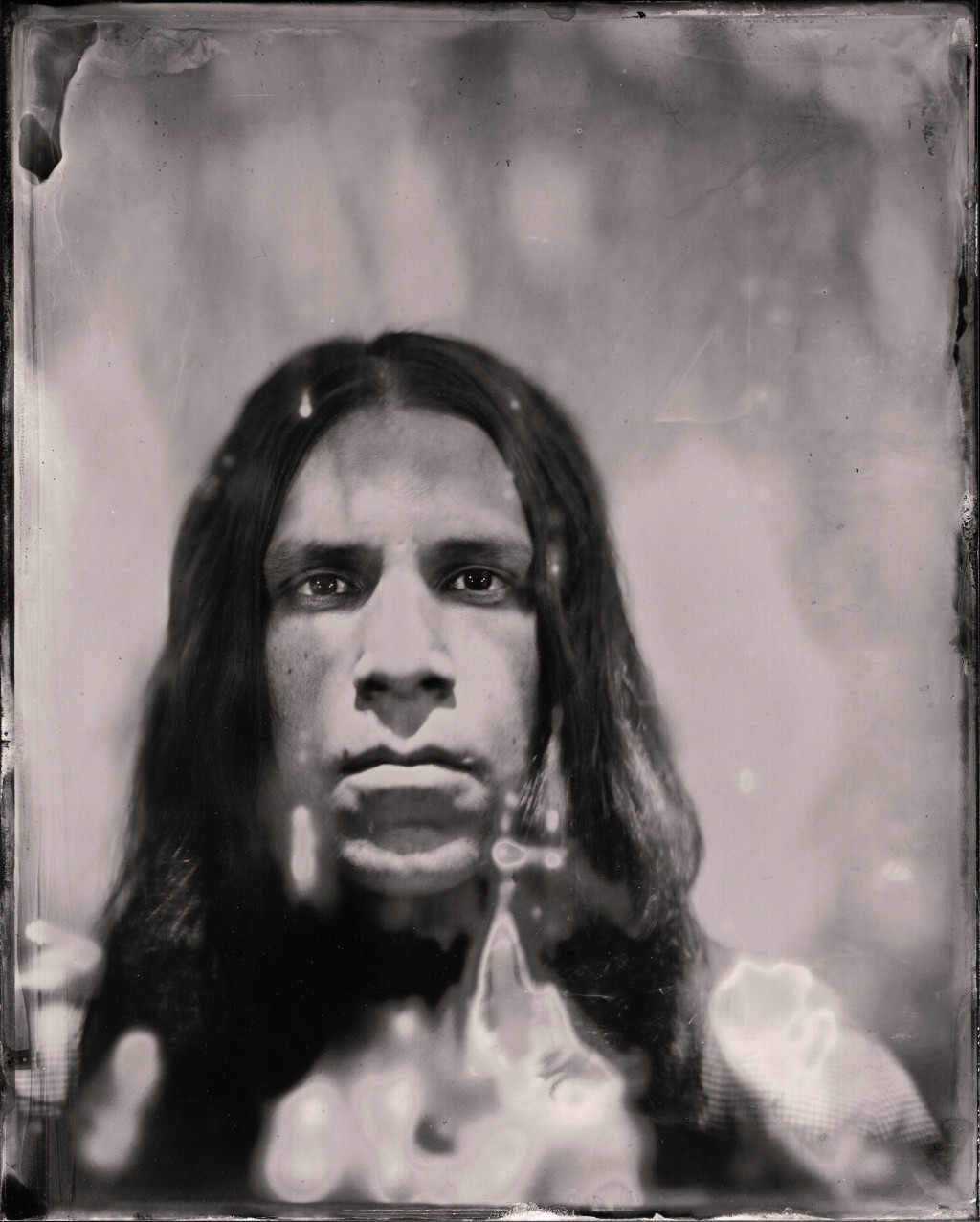

Jason Wyche/Courtesy the artist and Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Pointing out common requirements for museums to even consider relinquishing culturally significant holdings in their collections (temperature control, particular kinds of storage, etc.), Galanin said trading one form of capture for another is not necessarily the best way to think about correcting for the past. “The myth that our cultures wouldn’t be here without museums is still one that’s perpetuated heavily,” he said.

A series of works gathered under the title What Have We Become? centers on carvings of the artist’s face from thousands of pages in an anthropological study published by the Smithsonian in the 1970s. The works, Galanin said, deal with “homogenizing Indigenous knowledge and how that shapes identity and what we can or can’t be.”

Anthropological studies privilege certain kinds of knowledge over others, and the notion that studies of the kind might confer worth on their own is wrong-headed, Galanin said. “Our elders’ words are valued only after they’ve been processed through academia or anthropological texts, and then they’re devalued when conversations come up.” An example is the wealth of knowledge accumulated by local communities over thousands of years about the waterways around Alaska and the transformation of fisheries as a result of climate change. “When our elders speak about the health of the sea and land, it’s deemed memory and myth, and not really entered into scientific reports with numbers that start often in the ’70s. It becomes myth or this ‘other’ that is pushed aside when it doesn’t serve capitalism.”

An arresting work splayed out on the floor nearby serves a similar point, with what looks like a bear pelt fashioned from a U.S. flag under the punning title The American Dream Is Alie and Well. The bear is festooned with gold leaf and has .50-caliber ammunition for claws—and speaks to notions of trophy-keeping as a component of colonial practice at odds with indigenous ways of treating the remains of a kill. “Our relationship to everything that we do is connected to a form of respect and spirituality and understanding,” Galanin said, while noting an analog between approaches to hunting mementos and objects on view in museums. “Those objects are cared for with humidity control, dust control, etc., but historically, they were also poisoned through conservation techniques with arsenic and defaced with museological numbering. They are not cared for culturally and spiritually in those spaces, and that’s something that we can’t escape as Indigenous people. If we seek to connect with our ancestral past through these objects, it requires a lot of effort, funding, and travel, and not everybody has access to that.”

Jason Wyche/Courtesy the artist and Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Damage and disrespect are not reserved for museums, either. “There’s a whole economy where our aesthetic is appropriated and misappropriated,” Galanin said in front of The Imaginary Indian (Totem Pole), a work from 2016 that features a wooden statue seemingly dissolving in front of wallpaper in a display that greets visitors stepping into the gallery by the entryway. Based on Indigenous patterns, totems of the kind are actually carved in Indonesia before being shipped to Alaskan tourist markets “as a curio,” Galanin said. “Entrepreneurs exploit two communities: the Indonesians for cheap labor and the culture they take from.” The objects, in turn, become “ghost-like shells” in every way at odds with At.óow, a Tlingit word for what Galanin described as tangible and intangible property in the form of treasured cultural objects. “Ceremonial objects have spirits and lives,” he said. “They’re not owned by somebody—they’re your grandchildren’s children’s.”

An especially haunting work in the exhibition is Indian Children’s Bracelet (2014–18), one of three such pieces of jewelry alluding to forced removal and matriculation into boarding schools among Indigenous kids. “Part of the work is that all three are in separate institutions,” Galanin said of a set purposely split up and dispersed so far between the Portland Art Museum in Oregon and the Alaska State Museum. (The one in the gallery show is currently looking for a home, in an institution or otherwise.)

The legacy of mistreatment of children is only one aspect of “how our histories are often either ignored, erased, or not really spoken about,” Galanin said. “Society generally likes to consume our imagery and art forms without conversations about us or our experiences. Often it’s our iconography that people want, without any actual connection to people or recognition of the multigenerational impact on our communities.”

Jason Wyche/Courtesy the artist and Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Peering into a series of pointedly abstract prints in the show referencing a type of ritualistic dance, Galanin recalled early reviews of the Whitney Biennial that criticized certain artists for not being radical enough or working at an aesthetic remove from subject matter detractors would have liked to see engaged more directly. But his iconic work in the Biennial—a woven prayer rug resembling a television screen broadcasting white noise (a smaller version of which hangs in the gallery show)—enlisted abstraction in part to point out how, historically, abstraction has often not been afforded to certain artists expected to work in culturally specific ways.

The irony is especially troubling when those culturally specific ways have themselves long been abstract, and in any case, abstraction can be a language on its own terms. He called the dance-informed prints (which share the title Let Them Enter Dancing and Showing Their Faces) “an attempt at capturing cultural memory that is accessed through connections to land, through skinning a deer, through cleaning a salmon—and teaching your children to do all of that. We have these things ingrained in our memory and in our DNA. Whatever that feeling is, it’s not something you can look at, and it’s not something you can hold. But you can feel it, and it comes and goes.”

Jason Wyche/Courtesy the artist and Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Channeling a sense of place is integral to Galanin’s art, whether he’s at home in Sitka—as one can often see on an Instagram feed that finds him doing things like smoking salmon pulled from the Gulf of Alaska—or in a gallery in New York. “It’s important to help share the memory that everybody comes from a place,” he said. “The goal of colonization is often consumption and extraction, and then it just continues on. But it’s through memory and connection to places—and sharing that memory and connection—that we can demonstrate, share, and educate about ways of being in a world that are healthy for not just us but our future generations.” One of the aims of his practice, to that end, involves “challenging what forms of Indigenous art might look like, or how it’s activated through conversation and community.”

Offerings from that practice include artworks that make for ample opportunities to try to understand where they’re coming from. “It’s abstract language that’s been developed over 10,000 or 15,000 years of relationship to a place,” Galanin said. “Sometimes anthropology wants to understand how or what or where or when that came from. But that’s not answered by asking that question. It’s answered by being out on the land, being in a community, being in a place. Then you start to understand.”

[ad_2]

Source link