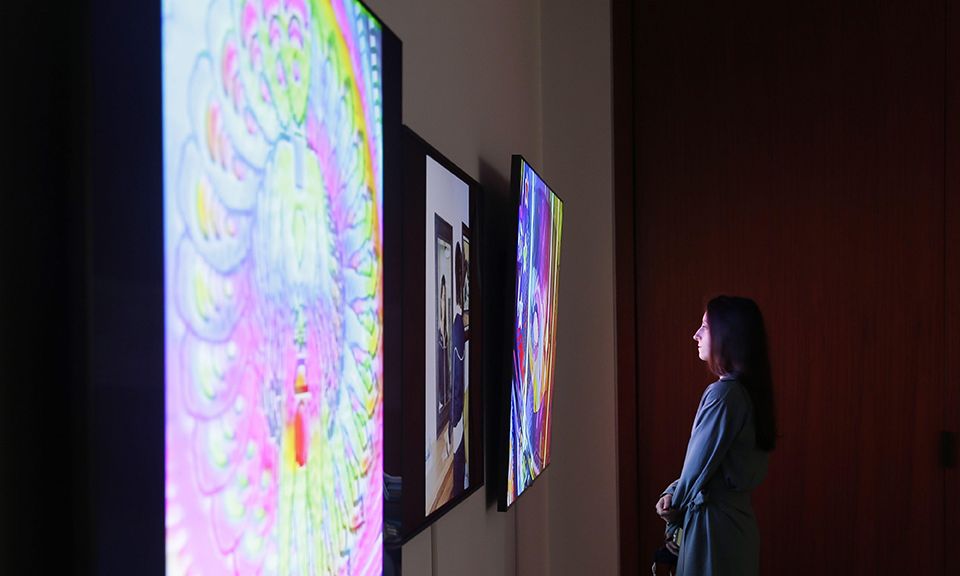

Sotheby's staged its first physical exhibition of NFTs in June last year, featuring the first NFT ever minted © UPI / Alamy Stock Photo

The gold rush following the auctioning of digital images as NFTs (non-fungible tokens) in the spring of 2021—notably, Beeple’s Everydays: the First 5000 Days fetching $69.3m at Christie’s—put the spotlight on digital art. For complex reasons digital art has struggled to receive due attention from the art world and market since the 1960s and is more than deserving of the increased interest. But the NFT boom and surrounding hype profoundly diluted both an understanding of what digital art is and how this art (or any art at all) is tied to NFTs.

The term “NFT art” suggests it describes a medium like video art or performance art, but the vast majority of so-called NFT art uses non-fungible tokens as a sales mechanism, not a medium. As non-interchangeable units of data stored on a blockchain, NFTs ultimately are nothing but digital certificates of authenticity. They reside on a blockchain, but the assets they authenticate usually do not.

The NFT boom has reduced the public image of digital art, which covers a broad range of creative expression, to individual reproducible digital images, animated gifs or video clips—the standard forms of digital collectibles and meme culture. There may be a segment of the crypto world that, through NFTs, has discovered the breadth and history of digital art and started supporting it, but that segment seems to represent only a small overlap in the Venn diagram of traditional art collectors and NFT collectors.

Since the 1960s digital art has made use of digital technologies’ real-time, participatory, generative and variable characteristics, and reflected upon their nature and impact. Pioneers of this art form, often referred to as the Algorists—among them Harold Cohen, Chuck Csuri, Herbert Franke, Manfred Mohr, Vera Molnár, Frieder Nake, Joan Truckenbrod and Roman Verostko—created algorithmic drawings in which pen plotters drew the results of artist-written code on paper.

In the ensuing decades digital art evolved into a variety of forms, from interactive installations, software art and net art to virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence and the small percentage of crypto or NFT art that uses the blockchain conceptually as a medium. Digital art still lacks full integration into the mainstream art world, but has been supported by a growing number of collectors and art institutions. The reproducibility and editioning of digital art functions similar to that of photography or video, and the paperwork accompanying the acquisition of digital art by an institution is usually much more sophisticated than the generic NFT smart contracts.

NFTs fulfil an authenticating function for a small fraction of digital art—digital images that “live” and circulate on the network. This ironically led to the now-common practice of artists and gallerists minting NFTs for stills or brief clips from more complex, often generative and interactive digital artworks that are available for lower prices than the excerpted images being offered as NFTs. Whether digital images benefit from the immutability provided by NFT authentication is yet another question. In his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Digital Reproduction (An Evolving Thesis 1991-95)”, Douglas Davis makes a case for the originality of the moment when we copy and revise digital images whose power often resides in the possibility of remix and free circulation.

A more sophisticated approach

Over the past year, hanging jpegs on the blockchain has become the norm in the creation and sale of NFT art, but artists have been laying the foundation for more sophisticated approaches for almost a decade. In 2014 Kevin McCoy and Anil Dash presented a form of proto-NFTs they called “monegraphs” (monetised graphics) at the New Museum during Rhizome’s annual “7 × 7” initiative pairing seven artists with seven technologists. McCoy and Dash’s monegraphs were conceived to support artists and creators, relying on smart contracts that included royalties and permissions for sharing and remixing. Support for creative practice rather than speculation was the goal. In 2017 the UK arts organisation Furtherfield, run by Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett, published Artists Re:thinking the Blockchain, highlighting art that conceptually explored the potential of organising natural and social systems through the blockchain. Artist Eve Sussman played with ownership in her work 89 seconds Atomized(2018), shattering the artist's proof of her acclaimed video 89 seconds at Alcázar into 2,304 unique collectible “atoms” or tokens that can be reassembled for a screening by a community of collectors. Jennifer and Kevin McCoy’s Public Key/Private Key (2019), commissioned by the Whitney Museum, explored tokenised donorship by giving a work to the museum and, through an open call, selecting 50 people who were able to assume, trade and transfer their donor title through their NFT. NFT works such as John F. Simon Jr.’s Every Icon (2021) set in motion a generative process, with the code stored on the blockchain.

The NFT gold rush has been investment-driven, with the art world following the economy rather than the other way around. To avoid the blockchain becoming digital art’s metaphorical ball and chain, the art world must acknowledge the art form’s rich history and its potential for creatively exploring the crypto space and decentralised distribution.

• Christiane Paul is the adjunct curator of digital art at the Whitney Museum of American Art and a professor of media studies at The New School