[ad_1]

Bridging multiple movements of artistic practice that blossomed in the 1960s, Walter De Maria challenged art in profound ways. A vanguard force within several major 20th-century art movements, he sought to connect the viewer and nature through a range of interactive sculptural installations.

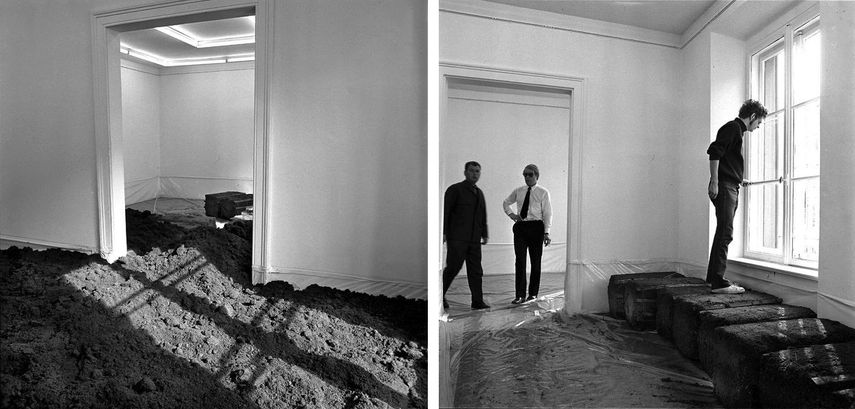

On long-term view to the public since 1980, The New York Earth Room is one of his seminal pieces exploring the relationship between art and the natural environment. An interior earth sculpture spanning over 3,600 square feet of floor space and consisting of 250 cubic yards of earth, measuring 22 inches deep, it is the third Earth Room sculpture by the artist, being first installed in Munich, Germany in 1968 and then at the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, Germany in 1974.

While the first two installations no longer exist, the installation in New York from 1977 is still there, defying change. We take a deeper look at this groundbreaking piece.

Creating a Bridge Between a Man and Nature

An important figure in four 20th century movements – Minimalism, Land Art, Conceptualism, and Installation Art – Walter De Maria drew upon both mathematical absolutes and elements of the sublime in his large-scale sculptures and installations. Dealing with massive scales not only in space but also time, some of his most ambitious works last for decades, whether indoors or out. One of those pieces is The New York Earth Room, located in a loft at 141 Wooster Street, in Manhattan’s trendy Soho district.

In 1960, De Maria called for “meaningless work”, art that does not “accomplish a conventional purpose.”[1] He followed this call with a dizzying period of experimentation. Previously working within Minimalist and Conceptualist structures, he became involved in the emerging Land Art movement in the late 1960s, searching for a diverse contextual language between art and the natural environment.

Developing a conceptual approach to earth-based works, he both used the landscape as an immersive canvas in large-scale land works and brought nature into the gallery space. In 1968, when he first filled the Galeria Heiner Friedrich in Munich with dirt, he also made the site-specific earthwork Mile Long Drawing in the Mojave Desert.

In 1977, the German art dealer Heiner Friedrich hosted The Earth Room as an installation at his New York gallery at the Wooster Street space. Initially meant to last for only three months, the installation still bides its time. In 1980, Friedrich helped found the Dia Foundation, an art organization dedicated to preserving De Maria’s work in perpetuity. Iconic De Maria’s works Lighting Field from 1977, Vertical Earth Kilometer from 1977, and Broken Kilometer from 1979 are also under the purview of Dia. “Bring the art to a place,” Friedrich stated once, “and let it speak over time.”[2]

The Sanctuary of The New York Earth Room

In a big loft amidst the consumer chaos of Soho, in a city of New York where people are money crazed and desperate for space, there is a huge space filled with dirt, standing unchanged since the late 1970s. In the bright lights of New York, the Earth Room remains a quiet sanctuary that forces you to experience rather than grasp. Profound in its mass, it draws the viewer in, offering a place where one can get a sense of expanse and be reminded of the horizon. Barely announcing its presence to those on the street, it also reminds us how nice it is when things don’t change.

Upon entering the gallery, one can feel the rich smell of soil and sense the warm humidity of the air. The installation spans three gallery rooms, while a knee-high sheet of Plexiglas boxes off the viewing area, allowing you to see how deep the dirt is. With dirt running from wall-to-wall, the vantage point is fixed, encouraging the visitors to take the experience in.

In a 1972 interview with Paul Cummings, recorded for the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, De Maria said:

Every good work should have at least ten meanings.[3]

However, he was determined about staying silent on the intention behind the Earth Room, describing it only as “a minimal horizontal interior earth sculpture”. It is this very absence of imposed meaning that is essential to this work. At the same time, Earth Room is imbued with meaning and truth, forcing a reflection on the world we live in, mainly through juxtaposition and contrast.

An Unchanging Piece That Evolves

Since De Maria’s death in 2013, the painter Bill Dilworth has been the public face of Earth Room. A caretaker of the installation since 1989, he has been attentively watering, weeding and ranking it each week and scrubbing the walls clean of mold. As he explains, it is the same earth as forty years ago and he attempts to keep it looking like it’s the first day. The important thing is that the dirt was never sterilized, but it was full of life. When he first started his job, half a dozen mushrooms would pop up a week. However, the nutrients that supported them were consumed over time.

In an attempt to describe the piece, Dilworth says:

It’s art, it’s earth, it’s quiet, and it’s time.[4]

As he explains, because of its undefinedness, it is a generous work that is easy to like and easy to live with. However, the context of the work is always shifting. As he explains for Paris Review, “The Earth Room is meant to be unchanging; nevertheless it evolves.”[5] Similarly, his relationship with it is continually refreshing.

Visiting and Revisiting The New York Earth Room

In the above-mentioned interview, De Maria said it was the most beautiful thing to experience a work of art over a period of time. Indeed, with the right amount of time and space, the art comes to life. The New York Earth Room is permanent and unchanging in a city that is constantly evolving, a city predicated on relentless change. In a city where everything is for sale, The Earth Room has stood silently for four decades, remaining economically useless. It is also a piece that escapes the grasp of the art market and stands in defiance of the commercialization of art.

By placing something so simple and commonplace into a gallery setting, De Maria pushed the boundaries of what art could be. This profound monument to simplicity invites the viewers to rethink one’s relationship to nature. In a bustling urban setting of New York, it proposes dirt as more valuable that it is often understood to be. It speaks to our fundamental search for balance between nature and the city, and for this, it rewards being visited and revisited.

Editors’ Tip: Walter De Maria: Meaningless Work by Jane McFadden

Featuring in-depth analysis of many previously unknown works and correspondence, Walter De Maria: Meaningless Work offers the first major critical account of De Maria’s broader range of interests. After calling for “meaningless work” in 1960, the resulting work reflected shifts in how we understand the sites of art during an era of moon shots and road trips, of wars that moved from jungles into living rooms via electromagnetic waves. It helped us understand ourselves and how race, gender, and sexuality vie for space in the social realm. By bringing to light De Maria’s lesser-known works, this book challenges established histories and methodologies for the art of the 1960s and ’70s, while also exploring De Maria’s own obsessions with art’s uttermost possibilities.

References:

- De Maria, W. Compositions, Essays, Meaningless Work, Natural Disasters, 1960

- Anonymous. Interview with Bill Dilworth. Acne Paper, Issue 12 [November 16, 2017]

- Anonymous. Oral history interview with Walter De Maria, 1972 October 4. Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art.

- Ibid, Acne Paper

- Chayka, K. (2017) The Unchanging, Ever-Changing Earth Room. The Paris Review

Featured image: Walter De Maria – New York Earth Room, 1977, via embodiedartsjsu.blogspot.com; The New York Earth Room 1977, via socks-studio.com. All images used for illustrative purposes only.

[ad_2]

Source link