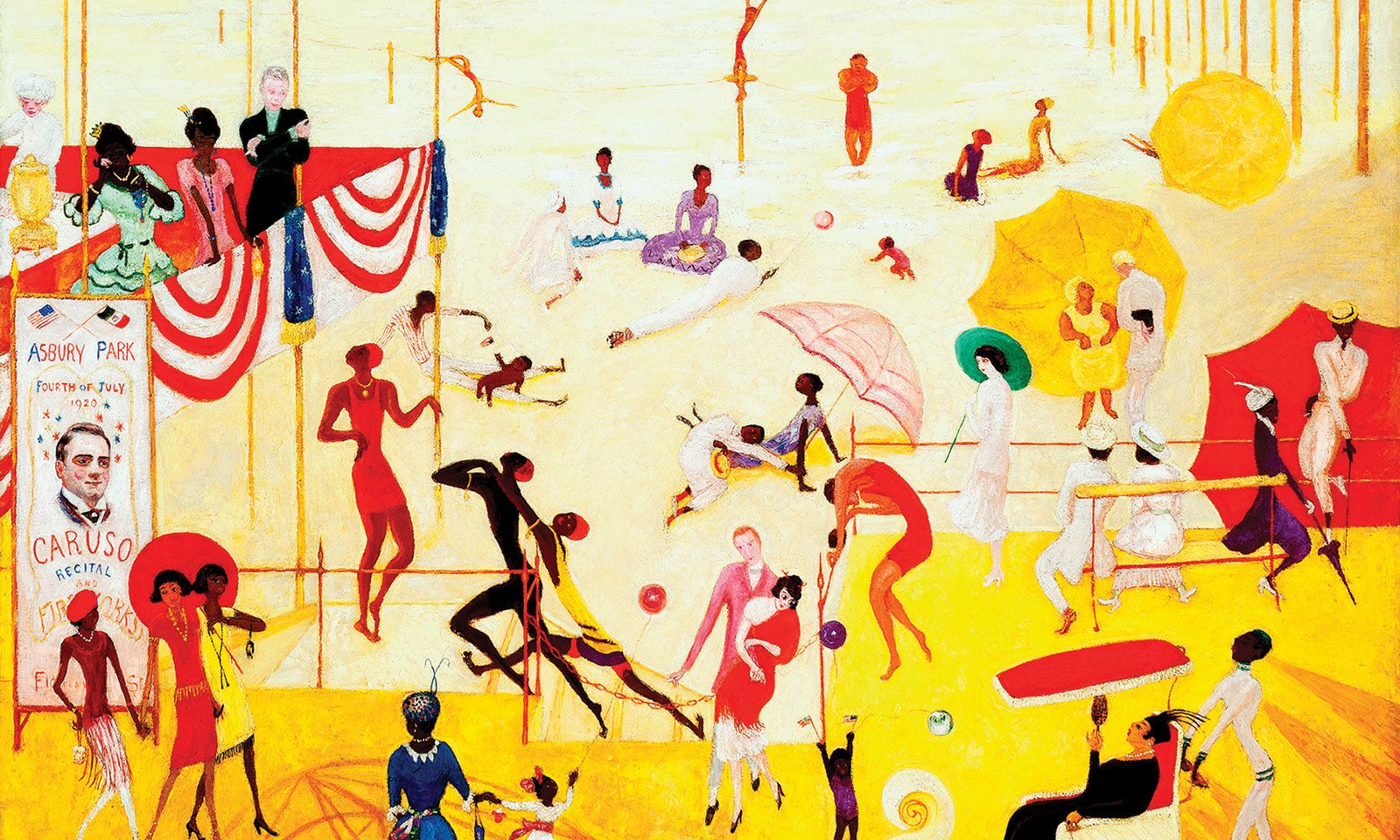

Florine Stettheimer placed herself in many of her paintings; here in Asbury Park South (1920), she is seen carrying a green parasol Collection of Halley K. Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld

Florine Stettheimer is the woman under the green parasol, stage right of Asbury Park South (1920)—an exuberant 4th of July scene, set on a golden New Jersey beach. Her self-portrait is easy to spot because, as always, she stands alone: a stylish observer dressed in white. Nearby, Marcel Duchamp escorts actress Fania Marinoff, as photographer Carl Van Vechten gazes out from the balcony. This group of celebrated friends seem to be enjoying a whimsical day of sandcastles and promenading. But the enlightening Florine Stettheimer: a Biography tells us otherwise. Asbury Park was among the first segregated beaches on the US east coast and the African American section was where sewage emptied into the ocean. Stettheimer considered this representation to be among her strongest paintings, exhibiting it more than any other during her lifetime. Rococo glamour and theatricality paired with cutting social commentary: such is the work of this extraordinary painter, designer, and poet.

Stettheimer (1871-1944) was born in Rochester, New York, of a wealthy German-Jewish family, training at the Art Students League of New York and then living in Stuttgart and Munich. By her return to New York in 1914, Stettheimer’s style demonstrated influences from both Symbolism and Post-Impressionism. In this comprehensive study of the artist’s life and work, Stettheimer scholar Barbara Bloemink expands on her 1995 biography, championing the painter’s contributions to Modern art as original and feminist. “She created a unique, theatrically-based, experiential style that was one of the first to consciously depict broad subject matter through a female, rather than the traditional male, lens,” writes Bloemink. “[She] was one of the first artists to document many of the central characters, events and social issues that characterised the first four decades of 20th-century New York City.”

Stettheimer, who priced her canvases at the modern-day equivalent of almost $4m to avoid selling them, has been a cult favourite since her death. But Bloemink argues that her work has been read superficially until now. She elucidates the historic context for Stettheimer’s paintings, aiding readers to look beyond the seductively decorative surfaces to see subversive depths. The work Beauty Contest: to the Memory of P.T. Barnum (1924) appears to idolise a blonde beauty contestant, until you realise that her attendant is wearing a dress patterned with red swastikas. Spring Sale at Bendel’s (1921) captures women eager to nab a bargain, turning, writes Bloemink, “the act of shopping into a fantastic balletic comedy of commerce and consumption”. Stettheimer’s final, unfinished painting, The Cathedrals of Art (1942-44) illustrates infighting between major Manhattan museums, as a naked baby, representing contemporary art, is stalked by paparazzi and reporters.

Excerpts from many of Stettheimer’s poems are included here, giving them equal creative weight to her paintings. And her privileged and peculiar life is recounted with the kind of abundant detail that fills her canvases, down to the cellophane curtains in her studio, and the guests—Alfred Stieglitz, E.E. Cummings and Cecil Beaton among them—at her family’s famous salon.

Stettheimer “was like her work. Her work was like her,” Georgia O’Keeffe said in her eulogy of the artist. Van Vechten—frozen in the act of looking towards Stettheimer in Asbury Park South—wrote that “she was both the historian and the critic of her period… telling us how some of New York lived in those strange years after the First World War, telling us in brilliant colours and assured designs, telling us in painting that has few rivals in her day or ours.”

• Barbara Bloemink, Florine Stettheimer: a Biography, Hirmer Publishers, 440pp, 110 colour illustrations, £25/$30 (hb), published 27 January

• Karen Chernick is the former director of the Reuven Rubin catalogue raisonné project, a member of the International Association of Art Critics and a regular contributor to The Art Newspaper