[ad_1]

Cai Cohrs as young Kurt Barnert.

CALEB DESCHANEL, COURTESY OF SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

A young woman struggles to fight off the medics sent to take her to the sanitarium. Her nephew, unable to look away, shields his view with his hand, causing the scene behind it to blur. This focus-pull is meant to anticipate the blurred photorealist paintings that the boy will grow up to paint, but the equivalence is not even rough, neither aesthetically nor philosophically. This is only the first misguided conceit in Never Look Away, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s return to German cinema a dozen years after his Oscar-winning debut, The Lives of Others. An unabashed melodrama, Never Look Away is the polar opposite of the chilly, removed early paintings of Gerhard Richter, which, with forensic zeal, the film will purport to interpret.

Although names have been changed and fictional plot points introduced, biopics seldom have this film’s level of fidelity. Its lodestones are three of Richter’s 1965 paintings based on photographs: Aunt Marianne, holding the artist as a child; Mr. Heyde, the commander of the Nazi’s psychiatric extermination program; and Uncle Rudi, genially grinning in his Nazi uniform. The last may have been too banal for Henckel von Donnersmarck, who swaps him for a hissable villain—Professor Carl Seeband, an evil Nazi gynecologist and eugenics true believer. Professor Seeband may seem an absurd, camp confection—and Sebastian Koch, the charismatic star of The Lives of Others, pulls the audience’s focus every chance he gets. But according to Dana Goodyear’s chronicle of the film’s gestation in the New Yorker, the protagonist’s unrelenting tormentor was alarmingly real. It’s easy to see why Richter, who agreed to many hours of interviews with Henckel von Donnersmarck, has since distanced himself from the film.

The Richter character, here called Kurt Barnert (an alarmingly blue-eyed Tom Schilling), attends art school in Dresden with all the inchoate conviction of your average art student, reluctantly imbibing the Social Realist dogma well enough to secure mural commissions. Here he meets his future wife, Elly (Paula Beer), who bears an equally alarming resemblance to his aunt. Guess who Elly’s father is? Guess who sterilized Kurt’s aunt? And guess who will incessantly needle the young artist about his minimal talent and genetic inadequacy?

Tom Schilling as Kurt Barnert.

CALEB DESCHANEL, COURTESY OF SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

Professor Seeband even follows Kurt west to Düsseldorf, a hotbed of contemporary art where the young artist will have to forget everything he knows and start over—that is, when he’s not lying naked on top of or under Elly in their attic apartment. Sadly, all that copulating does not bear fruit. “Your pictures will have to be our children,” sighs Elly after a miscarriage. Oy.

But it’s in 1961 Düsseldorf—at the Kunstakademie, not in the attic—where the movie cracks open with an ingenious conceit: Joseph Beuys has been given full reign over the school, admitting students at whim, abolishing critiques, and requiring only their attendance at his perplexing lectures.

Kurt tours a school under the sway of Fluxus, guided by a spirited student (Hanno Koffler, channeling Günther Uecker as he hammers nails into oversized furniture) who declares that painting is dead, “just like folk dancing and lace-making and silent movies.” But Kurt will continue painting, cycling through Abstract Expressionism and slashed canvases as he searches for a style to call his own—that is, when the boys aren’t madcapping around with mops and buckets with fictional stand-ins for future dealer Konrad Fischer (David Schütter) and Blinky Palermo (Franz Pätzold) like they’re in A Hard Day’s Night.

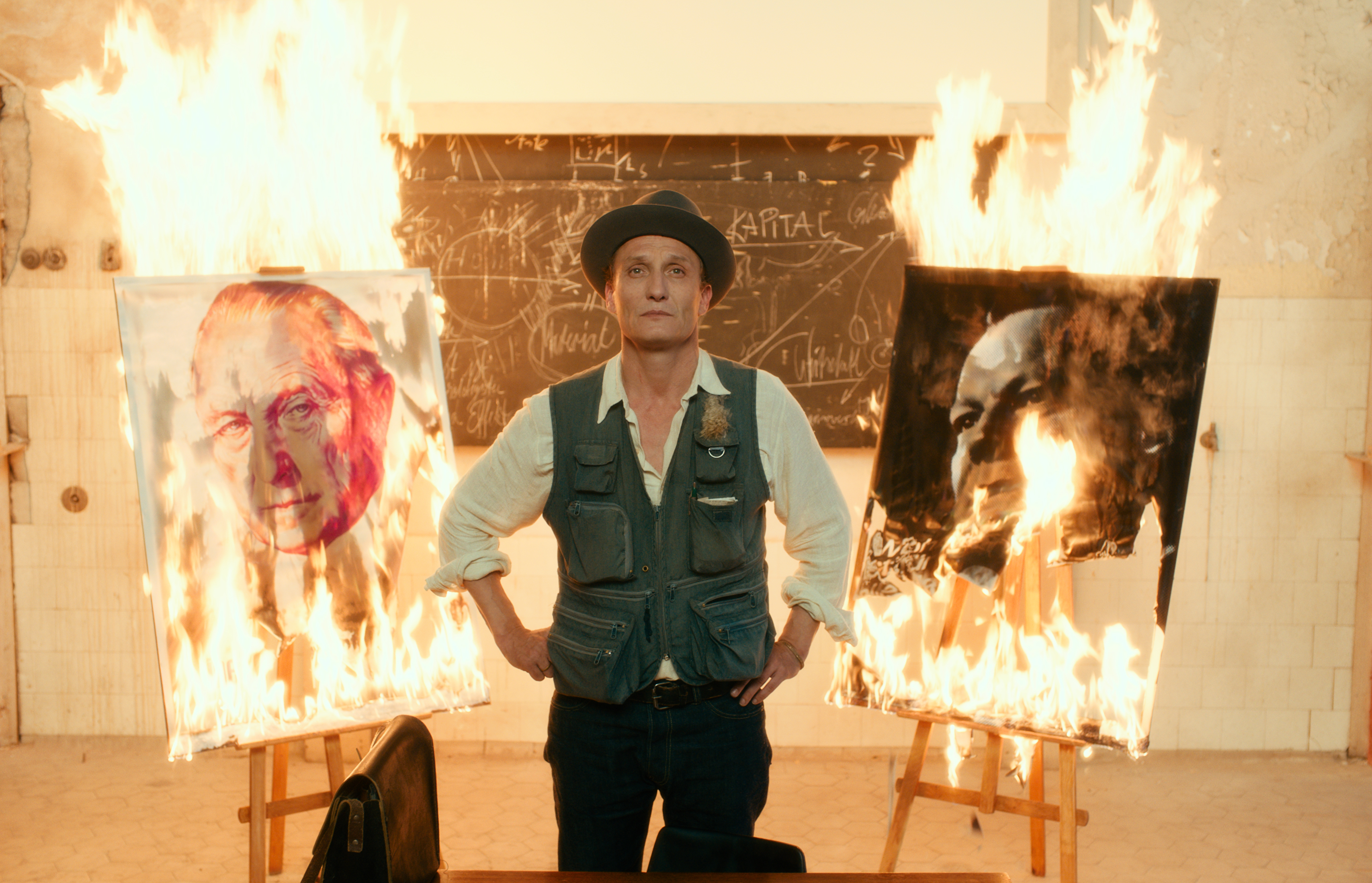

Oliver Masucci as Professor Antonius van Verten, the film’s Joseph Beuys figure.

CALEB DESCHANEL, COURTESY OF SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

But the real giggles come from Oliver Masucci’s Beuys, whose pseudonym is pointless to mention since the character is Beuys in everything but name. He’s Obi Wan to Koch’s Darth Vader—because Kurt’s milquetoast Papa (Jörg Schüttauf) never really cut it. Seeing a student flailing and failing, Beuys takes the boy aside and recounts his own origin myth: the plane shot down over the Crimea, the Tartars who nursed his broken bones by wrapping them with the felt and grease that became the materials of his art.

It’s a roundabout way of delivering that old saw: paint what you know. Soon Kurt finds his inspiration in the headlines: a photo of the arrested commander of the extermination program. So aroused is he by this breakthrough—even though it means raking over the memory of his aunt—that he has to go home and shove his wife against a wall, which at least is a refreshing change of position. Kurt ultimately merges his three paintings into one, in a moment of tackiness that, coming three hours into the movie, does not surprise, since it’s already been established that Henckel von Donnersmarck cannot leave well enough alone.

But truly, the film never recovers from the stench given off in its first hour when, in a scene of shameless bad taste, Aunt Elisabeth and her fellow inmates strip for the gas chamber. It’s the very definition of exploitation, using the Holocaust for thrills. In Richter’s Atlas, his compendium of photographic source material organized by subject, his five sheets of concentration camp photographs are followed by three of pornography. Read into this placement what you will, but there’s a reason Richter has never used the former.

At his triumphant first solo show, Kurt tells the press, as Richter has, that his sources are merely found snapshots, but Henckel von Donnersmarck knows better. An epic that paradoxically aims to cut its protagonist down to size, Never Look Away is not the first film about an artist that has little understanding of how art is made, but Henckel von Donnersmarck’s reductive smugness has an Oedipal dimension that does make one want to look away.

[ad_2]

Source link