[ad_1]

That romantic comedies often endorse behavior that would land real lovelorn suitors in prison has become a truism, and a well-grounded one. The genre abounds with grand gestures that smack of stalking and flirtations that should be considered minor sex crimes.

After watching “Sierra Burgess Is a Loser,” though, I have to admit that it’s been a while since I’ve seen a rom-com that could so easily be re-edited into a psychological thriller.

Netflix recently saw enormous success, both critically and popularly, with a classic but well-executed romance trope: the fake relationship in “To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before.” The streaming platform’s latest teen flick also turns to a time-tested plot. “Sierra Burgess” is a modern retelling of “Cyrano de Bergerac,” a tale that surely seemed ripe for rebooting in the internet era. Cyrano was the large-nosed hero of a 19th-century play who wrote romantic letters to the woman he loved, Roxane, on behalf of a handsomer man she preferred, but who lacked the wit to impress her intellectually. (Perhaps the most famous Hollywood adaptation is Steve Martin’s “Roxanne,” in which he wore a comically pointy false nose.)

But in bringing Cyrano, the original catfish, to a modern high school, “Sierra Burgess” only magnifies the ethical horror of the trope.

The titular Sierra Burgess (played by Shannon Purser of “Stranger Things” and “Riverdale” fame), our Cyrano, is a bright high schooler and social outcast; she lacks the taut, tiny beauty of a standard rom-com heroine, which is posited as the reason for her lack of popularity. She has one close friend, Dan (RJ Cyler). Her father (Alan Ruck), a brilliant novelist, bonds with her by making her identify the authors of passages he recites to her off the top of his head. Her mother (Lea Thompson), a gorgeous self-help author and speaker, tries to buoy her awkward daughter with affirmation mnemonics.

Her greatest tormenter, a popular cheerleader named Veronica (Kristine Froseth), sneers at her in the hallway, openly wondering what it’s like to be a reject, before stealing Sierra’s bulletin board flyer advertising her tutoring services. Later, when a hot boy from a rival school, Jamey (“To All The Boys” star Noah Centineo), approaches Veronica at a diner to ask for her number, she smilingly offers Sierra’s instead.

“Why would you do that?” her friend asks. “He’s, like, flash-your-boobs-in-Cancun hot.”

Glancing at the boy’s two less-attractive friends, Veronica sniffs, “Only losers hang out with losers.” Besides, she’s not interested in a cute high school boy ― she has a college boyfriend, Spence.

When Sierra starts getting texts ― including shirtless selfies ― from a handsome young man she’s never met, she quickly goes gooey over him. She’s soon horrified to discover he thinks she’s Veronica. But when Veronica gets dumped by Spence, who tells her that she’s not smart enough for his college buddies, Sierra sees an opening: She’ll teach Veronica how to sound smart in front of a college freshman (rather hilariously, by describing Nietzsche as a sexy, depressed German vampire), and Veronica will provide seductive selfies and cover for her in case Jamey approaches her in real life.

Netflix

When her bestie Dan hears about the scheme, he aptly describes this as catfishing, an accusation that is quickly brushed aside. But he’s right ― and the fact that we now have a word for what’s happening is emblematic of what has changed since the last major Cyrano-style rom-com. The plot of Cyrano is no longer wildly implausible. It’s commonplace.

“I know that he’s imagining her when he’s talking to me,” Sierra tells Dan. “But they’re my words. He’s falling for me.” The words matter, sure. But we’ve seen scenarios like Sierra’s play out again and again on the MTV documentary show “Catfish,” and here’s what happens at the end, pretty much 100 percent of the time: The catfisher and the mark do not end up together. Their romantic interest was largely based on their belief that the catfisher looked like a model; any appreciation for their personality does not generate sexual attraction for their physical form. (All the betrayal doesn’t help either.)

To overcome this plausibility gap, Sierra needs to seduce the audience, as well as Jamey, with her wit. Instead, their text and phone conversations are almost unbearably generic. They exchange goofy pictures of animals. On the phone, she peppers him with questions straight from a bargain-bin conversation-starter anthology: What animal would you be? What’s your favorite movie? Jamey gets the best lines, revealing that although he’s the high school quarterback, he’s also a sensitive, cerebral guy who sees football as a form of storytelling and is fascinated by the science of the universe.

When Sierra begs Veronica to take her place on a date with Jamey, she listens behind his parked Jeep (yes, she hides behind his car in a dark parking lot, nothing disturbing to see here) as he articulates his interest in the stars. She texts Veronica an appropriately deep and intellectual rejoinder: “I wonder if a star knows that it shines.” I had to pause the movie to pummel a couch pillow.

When I unpaused, the scene only got grimmer: Jamey tries to kiss Veronica, who stops him, covers his eyes with her fingers, and summons Sierra to lay one on him instead. The girls’ eyes shine with newly discovered solidarity as they trick a boy into kissing someone he did not consent to kiss.

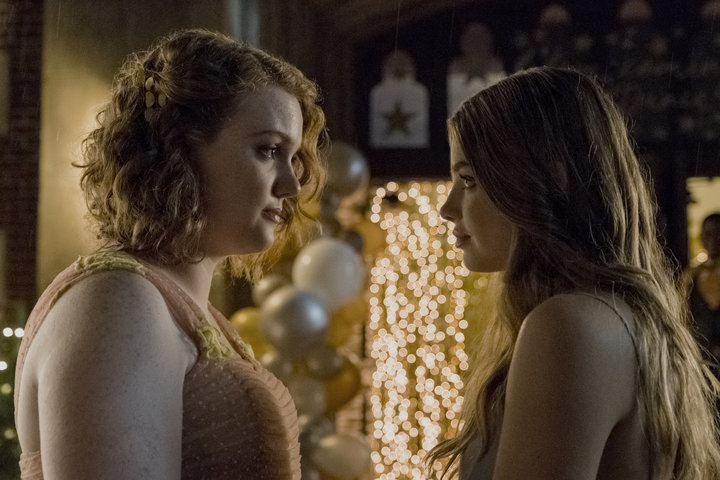

The blossoming friendship between chilly, guarded Veronica and awkward, intellectually snobby Sierra forms the true heart of this ostensible romance. Both hold each other in disdain at the outset, but come to find genuine pleasure in each other’s company. They’re in on the con together, and so their connection can be honest, despite the very real social barriers between them.

Aaron Epstein / Netflix

But as the movie crashes toward a standard rom-com conclusion, Sierra’s betrayals of those she claims to care about grow increasingly reckless and cruel. She’s finally confronted with how her self-perception ― as a victim, not a perpetrator ― has allowed her to hurt others. But oddly, the film does not ask her to redeem herself. She’s allowed to retreat into self-pity about her unconventional looks and her loneliness, and to be rewarded with a happy ending anyway.

As much as I love seeing him work his eyebrows onscreen, this time it’s not so satisfying to see the criminally charismatic Centineo declare his feelings to the no-longer-overlooked girl of his dreams. It feels unearned, unwarranted and underwhelming.

“Sierra Burgess” is anchored by three powerful leads ― Purser, Centineo and Froseth all bring charm, warmth and nuance to characters who could easily be flat or, in Purser’s and Froseth’s case, simply repellent.

It’s a shame that their skilled performances can’t soar due to the weight of the rest of the movie ― not just the eyebrow-raising plot, but the murky, depressing lighting more fit for the above-mentioned psychological thriller than a teen rom-com, and numerous offensive throwaway lines about weight, gender and sexuality.

(The dialogue is littered with casual transphobia and homophobia that goes almost entirely unchallenged. Sierra’s agreed-upon unattractiveness is conflated with her being a lesbian, a man and even a hermaphrodite.)

In the wake of Netflix’s catastrophic “Insatiable,” “Sierra Burgess” hardly registers on the scale of body negativity. But the underlying lesson ― that it’s what’s on the inside that counts ― strikes a similar chord. While Sierra comes to be loved for her words, the implication that she couldn’t also be desired for her body lingers. But what teenage girl (or anyone, really) wants to be loved in spite of her looks? Girls like Veronica are not the only ones who can or should hope to be found physically desirable, just as girls like Sierra are not the only ones who can or should hope to be found interesting for their minds.

This flaw ― the insinuation that some of us can only be loved in spite of our looks ― seems baked into the Cyrano trope, though perhaps a more creative adaptation could avoid it. What seems harder to avoid are any troubling messages about consent.

We all have the tools, now, to lie to people about what we look like to gain their romantic interest. We also have the tools to talk about how harmful it is. 2018 is an astonishing time to release a movie that portrays it as romantic and daring to trick a boy into kissing you by pretending you’re someone else. If we want a successful catfishing rom-com ― and hey, I’m all for trying! ― we’re going to have to come up with something less creepy than that.

[ad_2]

Source link