[ad_1]

If you’re a lover or student of American history, you’ll learn immediate bite-sized lessons from the book’s first pages, replete with a ledger of “Lies We Believe About the Man Who Could Not Tell Them” and lists of Washington’s favorite things: animals, frenemies and pettiest acts. Here’s why that’s brilliant: You already know he won the American Revolution, and if you’ve listened to or seen “Hamilton,” you know he did it with no navy and an army that was outgunned and outmanned. But did you know that Washington was a honey-obsessed surrogate father of four who named one of his dogs Cornwallis and ended up estranged from nearly every other revolutionary boldfaced name? After reading Coe’s book, you feel like you know him — his family, his desires, how he failed and grew and became the man who is on our money and inextricable from our national identity.

When pressed to comment on her contribution to a male-dominated field, Coe — who shouts out in her preface the transformative work done by Annette Gordon-Reed on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings and by Erica Armstrong Dunbar on Washington’s pursuit of Ona Judge, a runaway slave — marveled: “It’s never been a more exciting time to be a woman historian, but there’s never been more work to do for women and people of color because those are the groups that have been left out of traditional narratives… It seems as if I’m picking a fight [with this book, but] I just want history to be grounded in primary sources. And I think that I don’t view myself as personally disrupting the genre. I view myself as doing work that I know a lot of other women are doing.”

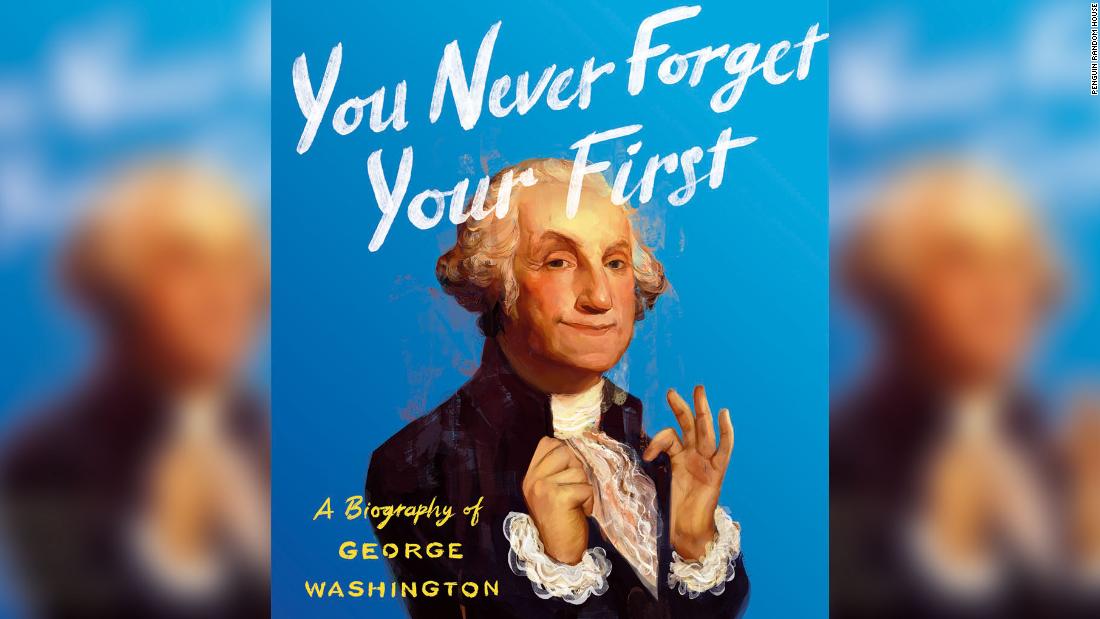

The book’s striking title began as a joke to her agent, Coe told me — a way of riffing on the need to explain why, after all the many popular biographies of the man of Mount Vernon, Americans need another life of Washington to read. Joke or not, as audiences began to react to the title, Coe recalled, “I thought as much as I might come to regret this title, it’s doing exactly what I want. It’s telling people that this is a different biography that is fun and serious.”

Coe succeeds in that quest admirably in “You Never Forget Your First” — the humor, individuality and sexual playfulness of its title reflects the illuminating influence the 21st century can have on the early American republic — revealing the simultaneous personal and political dimensions Coe believes the history of Washington’s life deserves.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and flow.

CNN: What is the origin story for your book? Why did you want to be the one to write it?

Alexis Coe: If you had told me years ago that I would write a book on George Washington, I would have thought that was insane. But I love presidential biographies, and I read them all. I usually read a few on one person at a time, and I emerge with a great understanding of who the president was. With one exception: George Washington. When I read books about him, I didn’t feel much closer to him.

I felt compelled to reassess what had been written on Washington. It’s very much history that’s been written for men, by men, about men. And it shows, from the portraits that are chosen, the titles, to the layout. So in the beginning I list all the diseases that he had, I list his nicknames, I list his frenemies, I list all the myths in a timeline so that people feel like they’re ready to take on early America in a way they may never have tried before. Everything that’s in there is meant to inform and delight, because history should be fun.

CNN: You close out the preface with a great line: “The outright fabrications may have stopped, but then mythmaking persists.” Why is it so important to debunk particularly the most tenacious myths about not only all presidents, but particularly this president?

Coe: I really want readers to understand why it’s significant that Washington was raised by a single mother, and then I want to proceed narratively as we would when that’s treated like a foregone conclusion. For example, in biographies about Barack Obama or Bill Clinton, we always learn that they were raised by single mothers. That’s important. Mary Washington lost her parents in young age, and then she lost her husband. She was the second wife, which means that she and her children got very little, and she and Washington had to struggle. In order to understand Washington, you need to understand that.

CNN: One thing that really stood out to me was your juxtaposition of military and marital familial history, where times of war and personal loss overlapped for Washington. It really shifts the narrative’s center of gravity.

Coe: When we typically read about Washington and the revolution, it’s battle, battle, battle, battle. Which is bizarre, because a general was not fighting in the battles, and these battles were being fought all over the colonies. He was mostly in his tent at one site writing letters, or overseeing other people writing letters. I wanted to know what those letters were about. That was George Washington’s experience in the war.

It’s important to understand what was happening off the battlefield and who he listened to during that time. Washington was a spymaster, he understood propaganda. He also had a lot of pull from home — his family was suffering. Remember, Washington was essentially the head of his household at the age of 10. He had all these pressures from home weighing on him in addition to an actual world war that seemed totally unlikely that he would win. The way he responded to those pressures is really revealing. His mother has often been portrayed as ungrateful or naggy. But she was completely isolated in the middle of Virginia, where the British had actually taken the capital, which sent (Thomas) Jefferson running home to Monticello. She had very few resources. She, a woman who was born to an indentured servant, wrote to her son that she never felt so poor in her life. She didn’t know if she was going to survive or if her son was going to. Yet Washington was much quicker to respond about ways to maximize the labor of prisoners of war on his plantation than he was to reply to his mother, who doesn’t know where her next meal’s coming from.

CNN: What would you say is the biggest or most significant myth about George Washington that’s still circulating?

Coe: Washington has always been presented to me as a sort of reluctant slave master who had this change of heart during the Revolution, and when he died, he did this incredible thing, which was emancipate all his slaves. That is about the most charitable reading you could possibly have about the situation. (Washington stipulated in his will that his own slaves were to be freed upon his wife’s death. Martha also owned slaves in her own right.) Washington did not see enslaved people as equal to white people. He did not have a change of heart during the Revolution. He was exposed to people who felt very differently about slavery who he respected and loved, like the Marquis de Lafayette, who then spent decades imploring Washington to emancipate his slaves and sent various proposals about how to do it.

The second thing that really needs to be clarified about this so-called “great emancipation” is that Washington only emancipated one man outright, and that’s the one person he thought of as exceptional: William “Billy” Lee, who had been his right-hand man in the Revolution.

CNN: What’s most important to understand about this myth about Washington as an emancipator?

Coe: One, he wasn’t freeing slaves outright. Two, they knew this, and he and they both knew that his will was going to be public, and that emancipation would look good for his legacy. (According to Abigail Adams, Martha emancipated Washington’s slaves a year after he died because she was terrified for her life. She sent several frightened pleas to family members when she thought that slaves were going to burn down her house.)

Not only that, but Washington knew that some of the enslaved people were likely going to be separated. His slaves and hers had married, they had had children together. Washington knew that Martha was not going to emancipate her own family’s slaves. We’re talking about 300 people, 123 people who belong to Washington and are free to go. And then when Martha died, their husbands, wives, children, grandmothers, grandfather, grandchildren, they’re spread among four different families all over the country as inheritance. It’s heartbreaking and I think it’s important that we know that before we celebrate this aspect of his biography quite so much.

CNN: Can you speak about Washington as a father figure?

Coe: It’s interesting to me that Washington’s biographers have fixated on his childlessness. I don’t think of Washington as being childless — because he was lousy with children. He was always raising someone’s child, whether it was his stepchildren, step-grandchildren, brother’s children, friend’s children, you name it. They were all over it and he was really involved. He was constantly writing them with advice, writing their tutors, writing to their schools. He was fathering hard. And then as far as being a father by being a founder of the country, he was fairly aware of that at the time.

Coe: John and Abigail Adams are an American dynasty and were very aware of that. Abigail Adams loved politics and she loved being in the thick of things. She had her own relationship with Jefferson and with other political leaders, and they were proud of their marriage and wanted to save their letters for posterity. And because we know that, because everyone knows that they wrote a ton of letters if they know anything about them, we perhaps assume that that was the norm, when in fact it was the exception.

Most people burned letters: Hamilton’s wife, Madison’s wife, Washington’s wife — they all destroyed the correspondence because they believed their public contributions were their public contributions and their private life was their private life. Martha Washington was not very interested in politics. It wasn’t the life she chose — it was the life she married into. We don’t know if Washington asked her to do this, but it definitely was the norm. We’ve still found a few letters, though. They’ve been found and stuffed in the back of a drawer, so they didn’t totally get off without us knowing anything about them.

CNN: I’m curious about what it’s like to write and publish a book about the first American president when we’re living in an era of what his critics describe as the worst.

Coe: When I began researching this book, I was actually at Mount Vernon at a Washington symposium the weekend before the 2016 election. And there were many people in the audience who asked questions about the presidency and who compared Washington to the chief candidates, to (Donald) Trump and (Hillary) Clinton. I left that symposium thinking that I would be writing a book on the first president of the United States while living through the presidency of the first woman.

The thing that worries me is I won’t believe that the Republican Party would do that. I don’t believe that they will make sure that this doesn’t happen again because I think that all they care about is power. And that is something that Washington feared and spoke to in his farewell address: that unprincipled men could take over who just want power and will listen to foreign influence, seek it out in order to maintain power.

CNN: I think you can probably predict what my next question is.

Coe: When people ask me, “What do you think Washington would make of this time?” I say: I think he would have a huge problem with Trump, but he would have an even bigger problem with the Republican Party. And they are everything he feared a party could be. This moment in America is really his greatest nightmare.

CNN: How will you spend President’s Day this year?

Coe: I haven’t gotten that question yet. This is going to sound very… it’s going to sound like a plug, but this President’s Day, the History Channel is releasing a three-part Washington series in which, with executive producer Doris Kearns Goodwin, in which I appear in and am also a producer on. So I will be watching that and hopefully talking about that.

CNN: No other Washington-related rituals in your life?

Coe: It’s funny. My life has been all Washington all the time for years, and there are gifts that people have sent me in my home to do with him. There’s a silhouette, and a bobble-head. But I didn’t purchase any of those. I believe in a bit of distance between biographer and subject, between historian and subject.

There’s something that’s been repeated by everyone about this book that I take as a bit of a compliment, which is that I have an irreverent take. That’s meant to imply that it’s funny and different, but the flip side of that is that we have come to accept that presidential biographies are reverent. And if you’re reverent, you’re biased, and if you’re biased, you shouldn’t be writing biographies.

I know that a lot of biographers in the introduction to their books write about what they do on Washington’s birthday or how they grew up with him or have a personal relationship with him. I didn’t have that — and I really plan to keep it that way. Also, I promised my husband no more Washington.

[ad_2]

Source link