[ad_1]

Just after 7 p.m. on Saturday, dozens of protesters marched south on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, through the bitter cold, toward the front steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, carrying banners with messages like “TAKE DOWN THEIR NAME” and “200 DEAD EACH DAY,” and chanting phrases like “Shame on Sackler” and “Shame on the Met.” Security guards and police officers watched from a distance, and camera crews rushed up to capture scene.

It was a reunion, of sorts. Just about one year earlier, in March, some of the same people had been on hand at the Met for the first action by Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (P.A.I.N.), a group started by photographer Nan Goldin to draw attention to the actions of the Sackler family, some of whose members have been accused of fueling the opioid crisis as owners of Purdue Pharma, the creator of the drug OxyContin. For that event, group members staged a die-in in the Temple of Dendur, in a wing of the museum bearing the Sackler name, throwing prescription bottles into the waters that surround the temple and collapsing to the ground.

P.A.I.N. has called on museums and other cultural institutions to remove the Sackler name from projects supported by the family, and for Purdue and Sackler family members to fund programs combating the opioid crisis. “They must use their blood money as direct restitution for the lives that have been lost,” a pamphlet distributed by P.A.I.N. on Saturday reads.

The action on Saturday began at the Guggenheim, with protestors staging a die-in inside the museum’s central rotunda, unfurling banners along its winding ramps, and raining down leaflets resembling prescriptions from above. Their target was the Sackler Center for Arts Education, which opened at the Guggenheim in 2001. Some of the leaflets featured words written by Purdue’s then-president, Richard Sackler, in a 2001 email that recently surfaced as a result of Massachusetts’s ongoing lawsuit against Purdue and members of the Sackler family: “We have to hammer on the abusers in every way possible. . . . They are reckless criminals.” That lawsuit claims that the company and its owners profited by misleading those who prescribed and took the drug about its potential dangers.

Responding to legal challenges, Purdue and the Sacklers have maintained that they acted appropriately in the development and marketing of OxyContin, though in 2007 the company and some of its executives admitted to understating the addictiveness of the drug and paid a fine of more than $600 million. They have also settled other lawsuits over the years. Purdue did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The Sackler Center at the Guggenheim was a gift from the family of Mortimer D. Sackler, one of the owners of Purdue until his death in 2010. The Guggenheim did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

The Met’s Sackler wing, which opened in 1978, was funded by the Sackler brothers Arthur, Raymond, and Mortimer. (Raymond, who died in 2017, was the father of Richard, the executive mentioned above.) Arthur’s widow, Jillian Sackler, has sought to emphasize that his death, in 1987, occurred well before the development of OxyContin. “Passing judgment on Arthur’s life’s work through the lens of the opioid crisis some 30 years after his death is a gross injustice,” she has said in the past through a spokesperson.

Standing at the foot of the Met’s steps, the activist Robert Suarez, who said his mother was one of the opioid crisis’ many victims, explained that the protestors intended “to send a message, a message of life and death—the life that is still on the planet and the death of people that we lost.” He mentioned “400,000 lives lost,” the number of deaths estimated to have resulted from opioid overdoses between 1999 and 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and went on, “All because of filthy, monstrous greed. The Sackler falmily has profited billions—and that’s with a B—billions of dollars from the loss of life, and that ain’t right.”

“That ain’t right!” some protestors, arrayed on the steps in front of him, shouted in response.

Suarez said, “For far too long, we’ve allowed pharmaceutical companies, like the Sackler family companies, to get away—that shit ends today.”

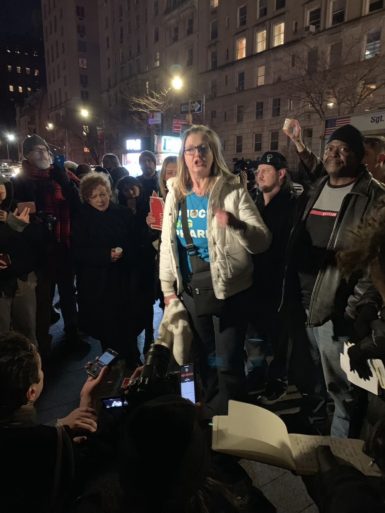

Goldin, cigarette in hand, read from a set of prepared notes. “We’re here to call out the Sackler family, who has become synonymous with the opioid crisis,” she said. “We’re here to call out the museums who allow the Sackler name to line their halls, tarnish their wings, to honor the family who made billions off the bodies of hundreds of thousands.”

Since the first protest last March, she said, “The Met has done nothing. They said they are looking at their gifting policies. What does that mean? They have not done anything. We are going to come back every year until something happens.”

Asked for comment on the protest, a Met spokesperson referred to a statement that the Met’s president and CEO, Daniel Weiss, issued last month that reads, “The Sackler family has been connected with the Met for more than a half-century. The family is a large extended group and their support of the Met began decades before the opioid crisis. The Met is currently engaging in a further review of our detailed gift acceptance policies, and we will have more to report in due course.”

Goldin has said she became addicted to OxyContin after undergoing wrist surgery. “I ended up locked in my room for three years,” she told the crowd Saturday night. “I came to and I realized it was time to speak out.”

“They should be in jail, next to El Chapo,” she said. “They should be charged with murder.”

“If not in jail, in the ground, next to Pablo Escobar,” Suarez joined in from alongside her.

Alexis Pleus, a woman from Upstate New York who said her son died as a result of overdosing on OxyContin, which had been prescribed to him for pain from wrestling, addressed the crowd in a booming voice. “They caused me, believing what the doctor said, to be an accomplice to my son’s death,” she said, referring to the Sacklers. “When my son talked of his pain, I said, ‘Did you take your pill?’ ”

“What matters to the Sacklers?” Pleus asked. “Money. Money, that’s what matters to the Sacklers. Money. So what do we want back from them? Money. I want that money. I don’t care if they go to jail, I don’t care if they go to prison. I want their money. You want to know what else I want? I want that fucking patent to the new Suboxone. And I want that Suboxone free for every single person who needs it . . . How dare they try to profit even off of this epidemic that they created?” (Her comments were a reference to reports last year that Richard Sackler had received a patent on a new drug that could help deal with opioid addiction; Suboxone, a drug marketed by another pharmaceutical company, aims to serve that same purpose.)

“Where’s Rhode Island at?” Michael Galipeau shouted as he took his turn, speaking as executive director of the Rhode Island Users Union, which had brought a contingent to the protest. “I’m a convicted drug dealer. I did my time,” he said. “Where is the Sackler’s time?”

L.A. Kauffman, a regular presence at P.A.I.N. protests, which have also been held at the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the Freer Sackler museum in Washington, D.C., closed out the speeches.

“This is part of a larger picture of impunity for the very rich in this moment,” Kauffman said. “We are standing in a plaza named for the detestable Charles Koch,” meaning David H. Koch, the billionaire industrialist known for funding climate-change denial programs. She also cited Rebekah Mercer, the onetime Steve Bannon backer and climate-science opponent who is a member of the American Museum of Natural History’s board, and Warren B. Kanders, the Whitney Museum vice chair whose company Safariland reportedly manufactured the tear gas used against migrants by the U.S. border patrol agents along the U.S.-Mexico border late last year.

“We see museums and cultural institutions glorifying the very rich and we also see them giving them positions of power,” Kauffman said. “The Sackler family is one of many who has been able to stand outside the law because of their great wealth and we are saying: the time is up.”

Activists began handing out sheets of paper with the phone numbers for institutions that have received funding from Sackler family members, and the chants started up again. “Say it loud, say it clear,” some cried. “Sacklers are not welcome here.”

[ad_2]

Source link