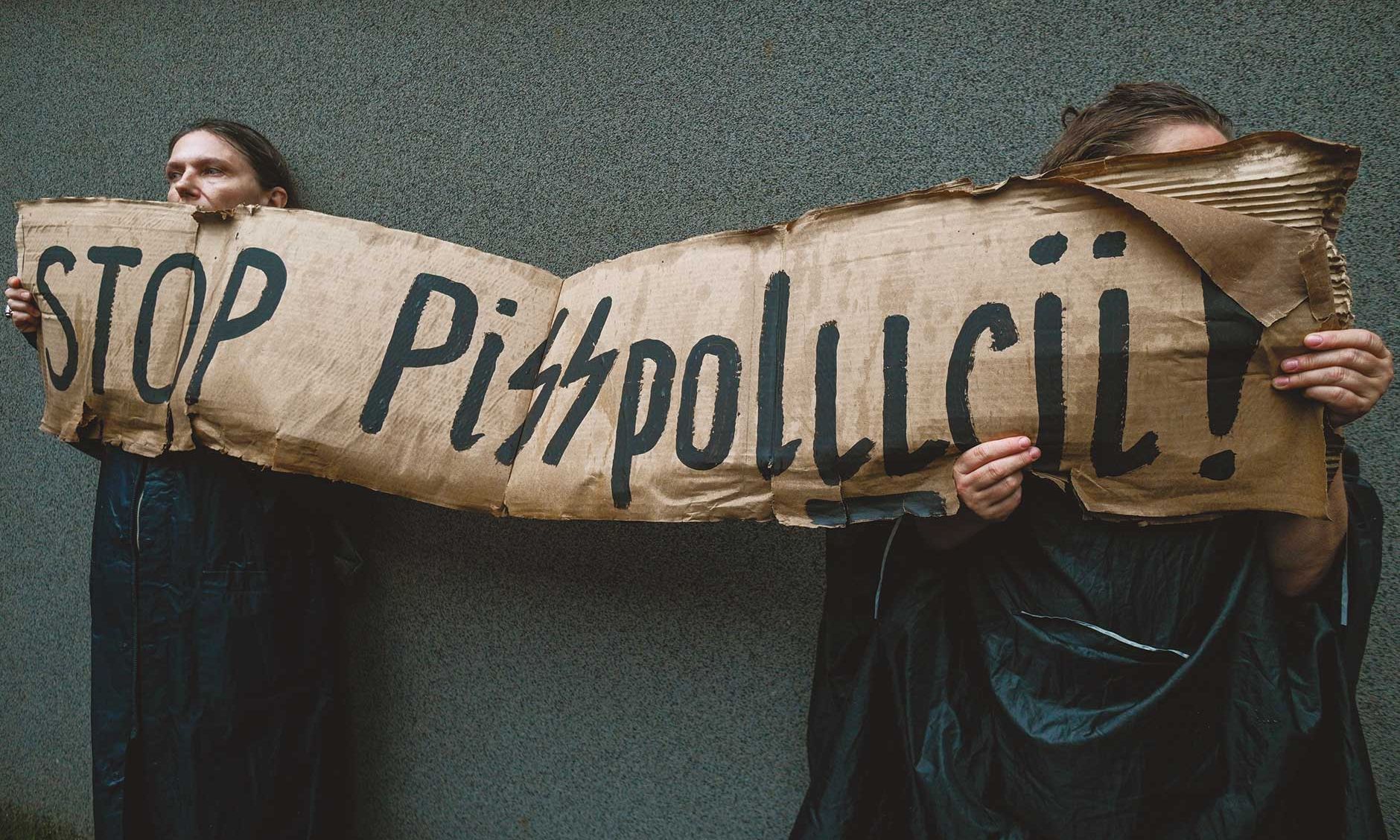

Taking the PiS: Since coming to power in 2015, Poland’s right-wing Law and Justice party has sparked regular protests

Photo: Artur Widak/NurPhoto via Getty Images

On 5 September Joanna Wasilewska, the longstanding director of the Asia and Pacific Museum in Warsaw, was dismissed from her post by the leadership of Masovian province, the region that includes the Polish capital. Sparking accusations of political interference, colleagues were quick to speak out in defence of Wasilewska, arguing that the museum, which dates to 1973, has lost a highly competent, modernising director whose decade in charge has seen numerous improvements, not least the opening of a permanent collection for the first time.

While Poland has become used to the dismissal of respected museum leaders in recent years, the international outcry over Wasilewska’s removal has been particularly pointed, with Steven Engelsman, the former director of the Weltmuseum Wien in Vienna, suggesting, “Poland has made itself into the pariah of the museum world”.

The controversy comes as Poland is in the middle of a heated election campaign, with the national ballot on 15 October set to determine the country’s next government. With the ruling Law and Justice party (PiS) seeking to win an unprecedented third successive term, its main opposition comes from the Civic Coalition, a political alliance fronted by Donald Tusk, the former prime minister and former president of the European Council.

The cultural community has often been at loggerheads with the right-wing PiS government, regarding both the handling of institutions and its hard-line, conservative approach to wider issues such as LGBTQ rights and abortion. One thing that stands out about the Wasilewska case, however, is that her dismissal was orchestrated by opposition politicians in the regional authority.

A petition organised in defence of Wasilewska notes that her case is “all the more disconcerting given that this time the actions have been undertaken by the politicians of the Polish People’s Party and the Civic Platform, parties that have frequently expressed their opposition and indignation against similar doings of the ruling party”.

Making a similar argument, a letter released by the Polish branch of the International Council of Museums (Icom) notes: “Once again, we are watching the infamous appropriation of public space by party coteries and arrangements, all the more acute because it is coming out of an environment that calls itself the ‘democratic opposition’.”

Jack Lohman, a former director of the Museum of London and current chairman of Poland’s National Institute for Museums, says the country’s mode of cultural governance is “not a new system invented by the current government but one that forms part of the DNA of cultural operations in Poland. We often think our British arms-length system is the only one worth following, where culture is supposedly totally independent, but the fact is that this system has no immediate history in Poland.”

Even so, many in Poland’s cultural sector have decided that the current system is not fit for purpose. The director of Icom Poland, Piotr Rypson, says the organisation is working on proposals for a “law on museums” that would establish “buffer bodies” at bigger institutions. He argues that such protections are needed given the shift in cultural policy since PiS came to power in 2015, with “liberal parties” previously keeping a “healthy distance from culture production”.

Jarosław Suchan, who was dismissed in 2022 by Poland’s ministry of culture from his post as director of the Museum Sztuki in Łodz, says that, while politicians of all shades have exploited the system, “there is an important difference in this aspect between liberal-democratic parties and populist parties such as PiS”. Whereas Suchan sees PiS as attempting to “take full control over institutions to subordinate them to one ideological agenda”, he argues that “violations” by opposition parties, such as the “unjustified dismissal of directors”, tend more to be “incidental, dictated by local, often personal conflicts and interests, which, of course, does not make them any less reprehensible.”

Explaining the need for “formal and legal solutions that would limit the possibility of political interference”, Suchan adds, “We want to prompt solutions to the opposition parties, hoping that they will include them in their electoral programmes—if only to distinguish themselves from ‘undemocratic populists’. This would lead to a fundamental strengthening of the autonomy of institutions—provided, of course, that the opposition wins.”